Will Technology Take Your Job?

A few months back, I was invited to speak at a forum focusing on the role of technological disruption in the economy and its impact (actual and potential) on workers in the Carolinas. Certainly the steady (some would say accelerating) march of information technology (IT) and robotics into the workplace, coupled with lingering anxieties from “the Great Recession,” has heightened workers’ insecurities about their own place in the economy of the future. To be sure, technological changes combined with other economic forces to dramatically alter the Carolinas economic landscape over the course of a generation.

Interestingly, during the transition, the region’s economy evolved to look less like it did in 1990s (overly reliant on manufacturing) and more like the national economy of today. Still, the region and its workers appear more exposed to economic disruptions. In some measure, this vulnerability can be viewed as a human capital development challenge. The states need to do a better job of training workers for today’s economy as well as preparing them for the disruptions that will inevitably come in the future, whether those disruptions are technological or cyclical in their origin.

Recent History with Technological Disruptions in Manufacturing

The Carolinas experience with the evolutionary effects of technology is relatively recent. North Carolina and South Carolina both have hard-earned reputations as “manufacturing states.” As recently as 1990, manufacturing firms employed nearly 1.2 million workers in the two states, accounting for roughly 26 percent of total payroll employment. But in the lead up to the new century, employment in some of the region’s mainstay manufacturing industries came under pressure from changing consumer demands and technological advances.

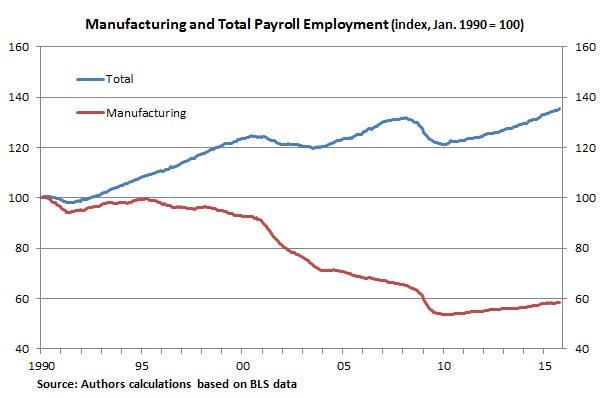

These technological advances were not limited to improvements in capital equipment, such as robotics and automation. They also included efficiencies gained from so-called process technologies – such as improved logistics, outsourcing, and (in many cases) offshoring. The result was that the two states saw manufacturing jobs erode during the 1990s and fall throughout the first decade of the new millennium, particularly during the “Great Recession.” Manufacturing employment fell by more than 493,000, or 42 percent, between 1990 and 2014. During this period of industrial restructuring, many argued that the loss of manufacturing jobs would doom the states’ economies.

It didn’t. While manufacturing jobs were on the decline, innovative businesses and people in the two states were creating jobs in other industries, many of which would have been hard to predict 10 years earlier. Firms brought new and innovative goods and services to consumer and business markets. And they created jobs, lots of them.

The chart below shows the history of employment in the two states between 1990 and today. As can be seen, total payroll employment in the two states plowed forward even as economic disruptions were having a materially adverse impact on manufacturing employment. On balance, workers sought and found work in other industries. And today the region’s industry structure looks more like the rest of the nation, even as it looks less like its former economic self.

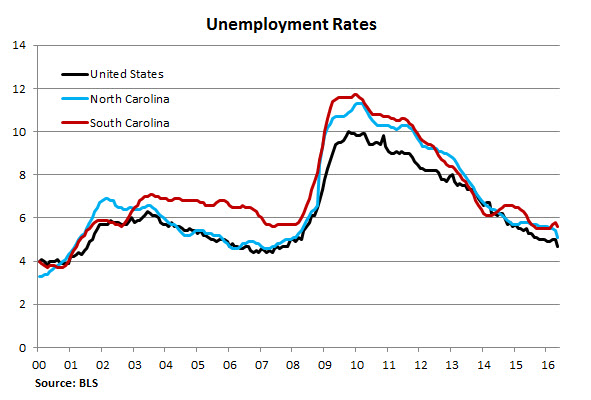

However, while aggregated data suggest that the Carolinas have weathered manufacturing job losses over the long term, it appears that total employment remains more volatile and susceptible to economic disruptions in the short term. During the Great Recession, for example, job losses in the Carolinas far exceeded the nationwide average (roughly 8 percent compared to a little more than 6 percent) and the unemployment rate in both states rose faster (see chart below).

Educational Attainment

So why is the states’ workforce more susceptible to economic shocks? And what can state policymakers do to enhance their workers survival skills? While there are myriad contributors to the problem and many potential solutions, skills attainment is a partial answer to both. There are many ways that researchers measure skills attainment and, more broadly, human capital development, but some of the most readily available and informative indicators are states’ educational attainment metrics.

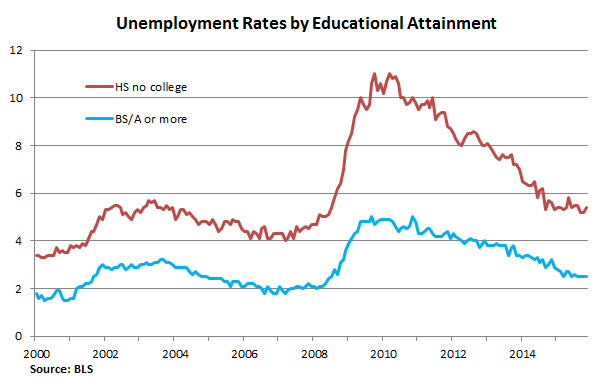

Higher educational attainment has many virtues, for society and individuals alike. Among them, statistics show that the more vested a worker is in his or her skills attainment, the more likely he or she is to participate in the labor force. So from a societal standpoint, more highly skilled workers portend more economic growth potential. On an individual worker level, attainment of postsecondary skills leads to higher lifetime earnings potential. It is well documented that workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher, on average, earn considerably more income over their lifetime than a worker who has completed no more than a high school diploma. And that earnings gap is widening.

But perhaps more important to the individual worker is the flexibility that higher skills attainment provides, especially during periods of economic disruption. At no time in recent history was that more evident than during the Great Recession. During the worst of that downturn, while the nation’s unemployment rate hit 10 percent, it did not rise above 5 percent for those workers with at least a bachelor’s degree (see chart below). The upshot here is the higher your educational attainment, the more opportunities you will have for employment and the more likely you are to stay employed, even in times of significant economic disruption.

Educational Attainment in the Carolinas

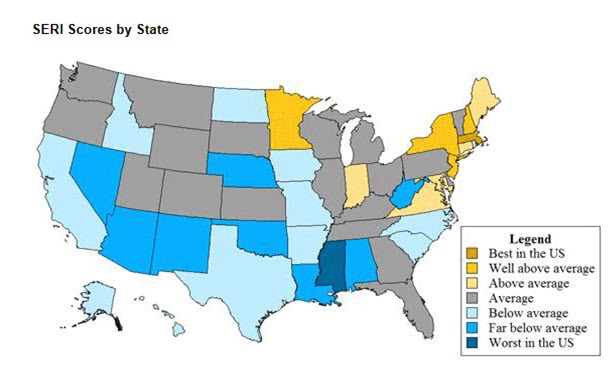

So then, how well-positioned are workers in the Carolinas, from an educational attainment standpoint, to survive and thrive in periods of economic duress and/or technological disruptions? Unfortunately, the preponderance of evidence suggests that the region is somewhat behind the nationwide average. Whether looking at high school graduation rates, college enrollment rates, or the percentage of the population with postsecondary degrees, the data show that both North Carolina and South Carolina fall below nationwide average levels of attainment.

Perhaps of more importance is the seeming underperformance in measurements of the states’ STEM readiness. With more technology being integrated into nearly all jobs, there is virtually universal agreement on the need to improve education in the so-called STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) coursework. In 2011, the American Physical Society derived a measure of STEM readiness by state using available metrics for student achievement and enrollment, as well as teacher qualification scores. Here again, the Carolinas fell below the nationwide average (see chart below).

Conclusion

The economies of North Carolina and South Carolina went through a painful adjustment process since the early 1990s as a combination of changing consumer preferences, technological advances, and cyclical disruptions dramatically reduced the number of manufacturing jobs. Over this time frame, the states have largely moved on in impressive fashion, but employment growth remains more volatile than in the nation.

Moreover, the jobs being created (manufacturing and otherwise) are very different than they were just a decade ago. Most require education beyond high school and at least a rudimentary understanding of IT and automation. Those jobs that do not require such skills are often low paying or prime candidates to be replaced by technology one day. So long as the Carolinas lag the nation in most measures of educational attainment, the region’s economy and its workers are likely to remain more susceptible to economic disruptions, technological or otherwise.

Have a question or comment about this article? We'd love to hear from you!

Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.