Growing Younger: Are Rural Demographics Shifting?

As the Baby Boomer generation ages, America has been "graying." The Census Bureau estimates that within the next decade, there could be more adults over 65 than children under 18. Geographically, rural areas tend to be older than urban areas and median age rose across both rural and urban areas from 2010 to 2020. More recently, however, the story has changed; in the last three years, many rural counties have gotten younger. And about a third of them are getting younger while growing their prime working-age population, a key group needed for economic and employment growth that can help lead to a long-lived rural resurgence.

Since 2020, Many Rural Areas Have Gotten Younger

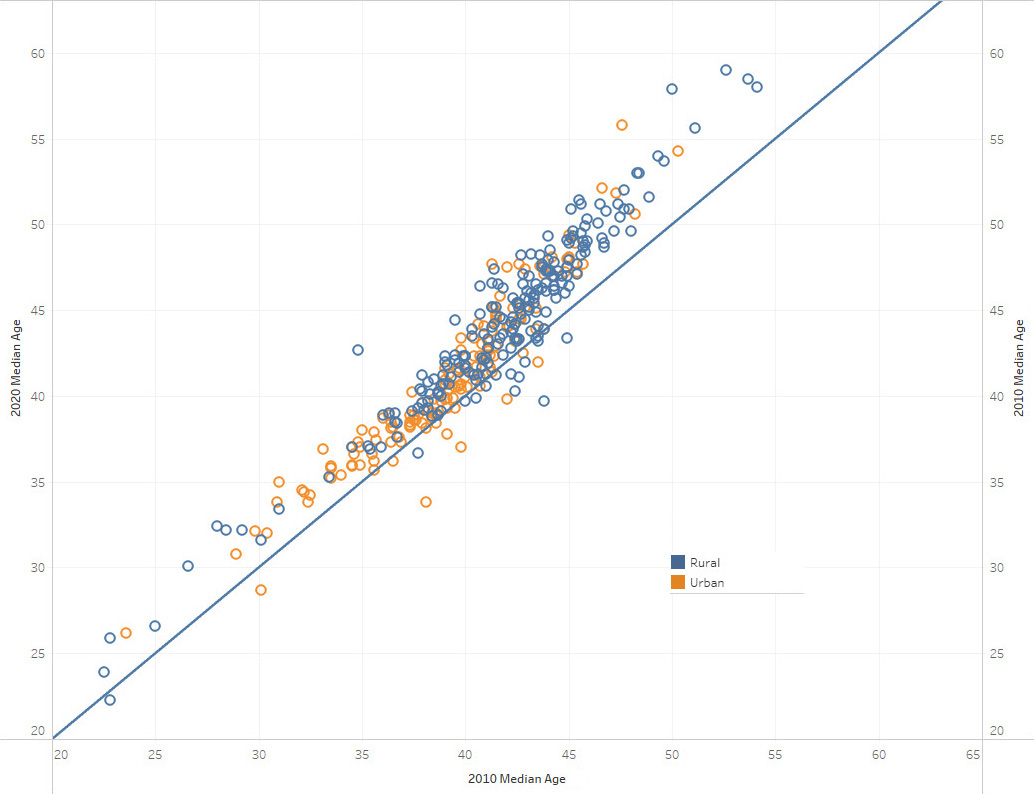

Between 2010 and 2020, nearly every urban and rural county in the Fifth District saw their median age increase. The chart below depicts a county's median age in 2010 versus the median age in 2020 — to the extent that a county is above the line, its median age in 2020 was above that in 2010. In addition, rural counties (blue) tend to have higher median ages compared to urban counties.

The above chart also shows that some rural areas grew older by a larger amount over this time period (dots that are farther from the line). For example, one of the largest changes occurred in McCormick County, S.C., where the median age rose from 50 in 2010 to almost 58 in 2020. Highland County, Va., had the highest median age of rural counties in our district in 2020 at 59, up from 52.6 in 2010.

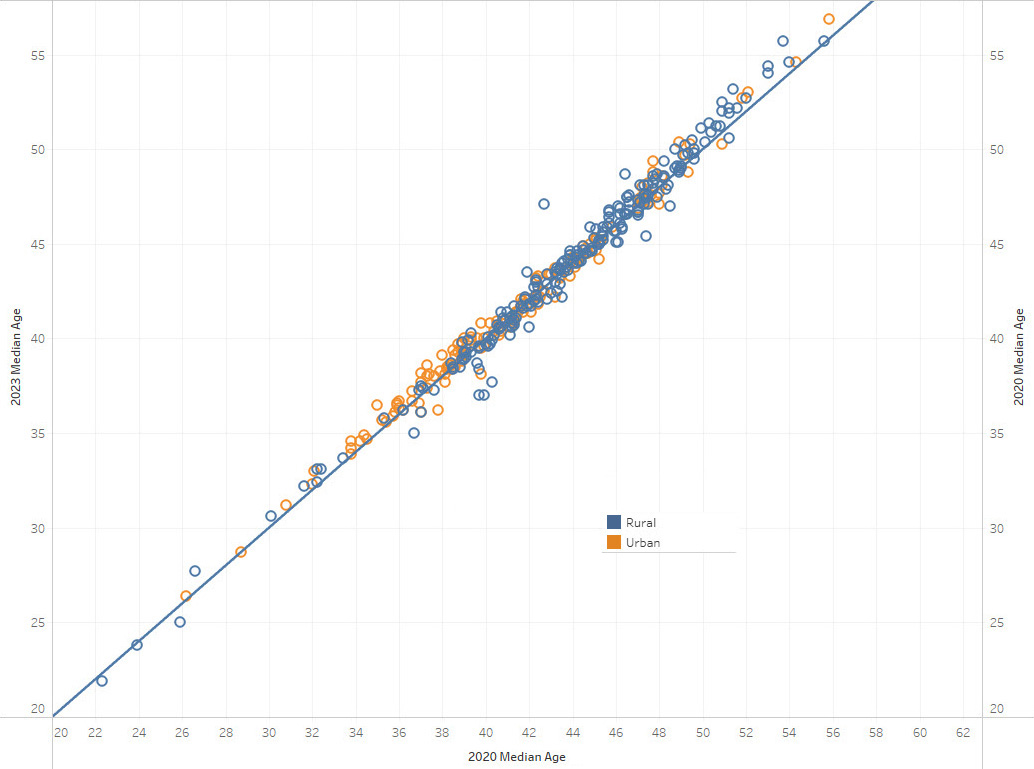

However, from 2020 to 2023, the median age declined in more than a third of Fifth District counties (240 out of 716 counties). Interestingly, more rural counties saw declines in median age than urban counties — 65 percent of the 240 counties are rural. What is more, some of the largest age declines occurred in rural counties.

What Factors into Median Age Changes?

Why might median age decline? One factor is natural change. All else equal, if the oldest resident in a county dies, the median age falls, just as it does if a baby is born. Another factor is migration. Out-migration of older residents or in-migration of younger people lowers the median age. Since rural areas tend to have smaller populations to begin with, median age is more sensitive to small changes in demographics. Of course, a decline in median age might not always indicate a more vibrant economy: A county experiencing population decline and net out-migration could also see a decline in median age.

On the other hand, growth in certain population segments matters for sustaining economic growth or slowing economic decline. For example, having a concentration of 25- to 54-year-olds (prime-age individuals) can motivate potential new businesses to open in those areas as the availability of workers is often a top factor for site selectors. Prime-age individuals are also most likely to have children, which helps to grow the overall population.

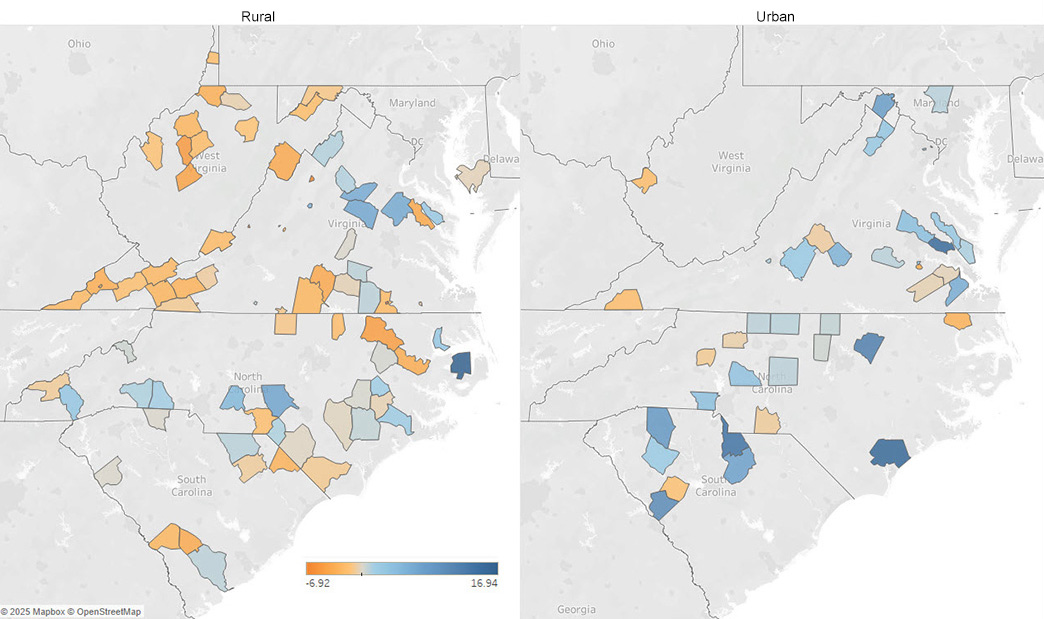

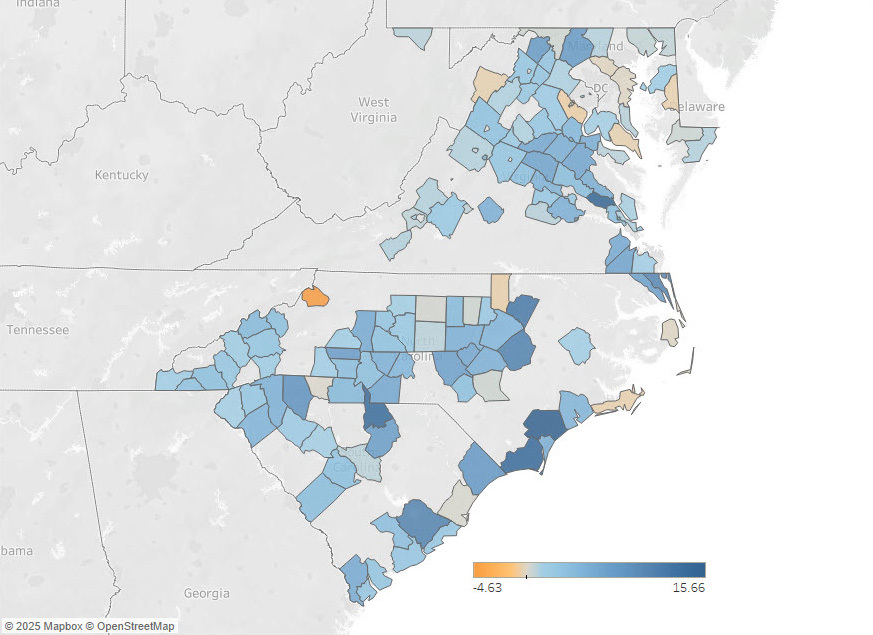

The map above shows the change in prime-age adults from 2020 to 2023 only in counties that saw a decline in median age. Urban counties (righthand map) were more likely to see a decline in median age accompanied by prime-age population growth. In fact, 73 percent of urban counties with median age decline saw growth in their prime-age population. On the other hand, only about 38 percent of rural counties that had a median age decline also saw growth in prime working-age adults. Those rural counties with a growing prime working-age population might be in store for longer-run population growth.

Prime-Age Primes for Growth

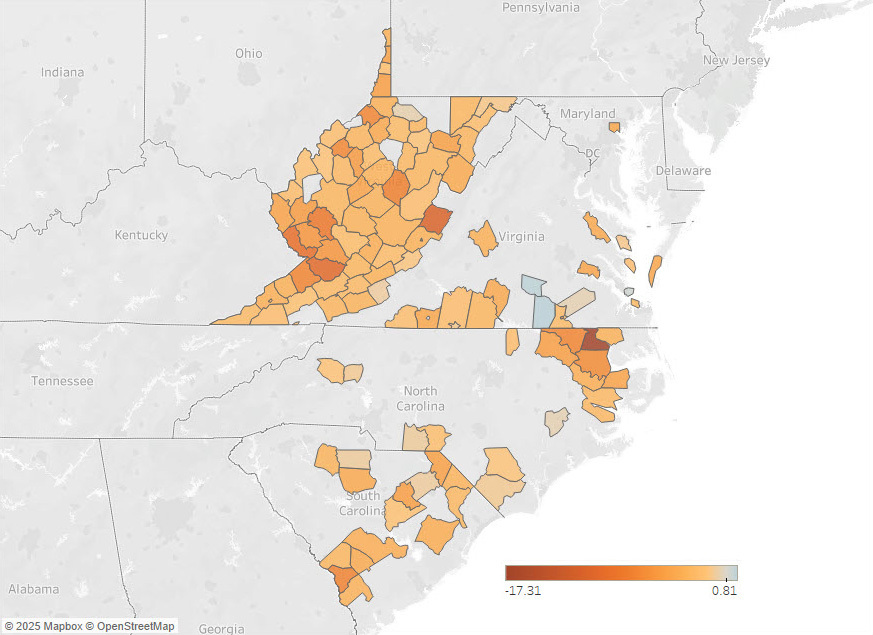

Growth in the prime working-age population matters for population growth in rural areas. Among counties that saw population decline from 2010-2023, nearly all lost prime working-age adults. Conversely, among growing counties, 93 percent had growth in prime working-age adults. This doesn't mean other population groups like children or seniors were growing or contracting, but the link shown between prime working-age adults and total growth is undoubtably strong.

The above maps highlight why growth in prime age adults might be important to the rural counties. If their growth is being driven by this prime-age population, it could set these counties on a path for longer-term population growth, as has been the case in most areas where this segment of the population has been growing.

Conclusion

Although the U.S. has been graying, many rural counties have actually grown younger over the last several years. Growing younger, however, might not be the right barometer for a vibrant economy: Urban areas are still more likely than rural areas to see growth in prime working-age populations. Those rural areas that have seen growth in prime working-age populations might be better situated to take advantage of economic opportunities and grow their population over time.

Views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.