Whom Do the Federal Reserve Bank Boards Serve?

The long-standing governance model of the Federal Reserve Banks, including their boards and the directors who serve on them, is under growing criticism. Calls are increasing for the boards to sever direct ties to banking and finance and become more diverse in their representation, as well as to offer more transparency to the public. As history shows, this governance model always has been the subject of political scrutiny, as public concepts of diversity — and the Fed's functions — have evolved over time.

The governance structure of the Federal Reserve System, including the leadership of the twelve Federal Reserve Banks, is increasingly drawing fire from a wide array of critics. Liberal groups have focused on Reserve Banks' boards of directors, which they believe are stacked too heavily in favor of private banking interests, too opaque, and insufficiently representative of women and minorities. The progressive coalition Fed Up, for example, calls for a ban on directors who have direct ties to banking and finance. It also has pushed for public nominations and public hearings for Reserve Bank presidents, who are currently selected by a subset of their Bank's nine-member board of directors (subject to approval by the Fed's Board of Governors). Coming on the heels of pressure from liberal members of Congress, the Democratic Party included language in its 2016 platform to prohibit executives of financial institutions from serving on Reserve Bank boards.

The leadership and board structure of the Reserve Banks also have conservative critics. Mark Calabria of the Cato Institute, for example, recently wrote that the Fed, in general, has a "diversity problem" of too many economists from elite East Coast schools staffing the most senior levels, on the Board as well as at the Reserve Banks. "You are guaranteed to have an institution that suffers deeply from groupthink, as well as being insulated from the everyday experiences of most Americans," he wrote, suggesting reforms that included a ten-year residency requirement for candidates seeking to become Reserve Bank presidents.1

By taking aim at the Fed, including its governance model, these disparate groups are finding common ground. Many of these critics fail to note, however, that the debate over the leadership structure of Reserve Banks is not new. The composition of Reserve Bank boards has been discussed and disputed throughout the last century. These arguments were especially intense in the run-up to the passage of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913, in the Great Depression, and during the civil rights movement and painful stagflation in the 1970s. The question has resurfaced most recently in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession, amid broader public scrutiny of the Fed. In fact, the debate over Fed governance, including Reserve Bank boards, is closely bound to the central tensions and grand compromises of American politics — encompassing the fights over local versus national government, progressive versus populist policies, and Wall Street versus Main Street economic interests. These arguments also reflect the tension between the desire for the benefits of a national bank and fears of financial monopolies and money trusts. The fact that these debates mirror such long-standing fissures in the American polity makes it all the more important to understand what the Reserve Bank boards actually do — and how these functions have evolved over time.

A Balancing Act

The German-American financier Paul Warburg, one of the key architects of the Federal Reserve Act, laid out a clear vision of how central bank boards should operate after the Panic of 1907 galvanized him to analyze America's fractured banking system. As he saw it, such a board should be "independent of politics" and not "swayed by selfish motives in its actions." At the same time, it had to be "thoroughly representative of the various interests and districts of the country ... non-political, non-partisan, and non-sectional." And its members had to be equipped to deal with "broad questions of policy affecting the whole country" while being knowledgeable of local and regional economies.2

The authors of the Federal Reserve Act sought to achieve this diverse set of goals by dividing the nine directors of each of the twelve Reserve Banks into three classes, with each class representing different economic and public interests. Class A directors were bankers, elected by member banks to provide professional expertise and represent the interests of those institutions. Class B directors were also elected by member banks, but they did not work for or own stock in those banks; instead they represented commercial and community interests outside of banking and finance. Finally, Class C directors were chosen by the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., both for their expertise in running large, complex corporations and for representing the general public. Class C directors could not serve as officers, directors, or employees of commercial banks while sitting on the board. However, under the framers' initial interpretation of the Act, two of them — those who served as the board's chair and vice chair — had to have "tested banking experience." In short, in the early years, five out of nine board directors had to have ties to banking or a substantial banking background.3 Under the modern interpretation of the Act, however, it is only one Class C director, the chair, who has to meet this requirement.

This structure made sense when the United States established the Federal Reserve. To set up this central banking system, Congress needed to convince bankers to provide expertise as well as funds. Federal and state governments did not spend a penny to establish the Fed. Instead, the Fed's founders convinced commercial banks to join the Federal Reserve System, and in doing so, invest tens of millions of dollars in the central bank, all paid in gold coin or bullion. The Fed used this gold to guarantee the value of the dollar, which at that time was on a gold standard.4

Using the model of a traditional corporate board, Congress envisioned directors as officials who would "perform the duties usually appertaining to the office of directors of banking associations and all such duties as prescribed by law," in the words of the Act. These duties covered tasks such as ensuring adequate staffing, establishing bylaws that employees should follow, and interpreting audit reports. As the Act's drafters saw it, then, it made sense to have professional bankers on Reserve Bank boards because they had the expertise to manage a bank. But just as importantly, Congress mandated that boards also have directors from outside the banking world to represent the public interest. This is one manner in which the Reserve Banks have a hybrid public-private governance structure.

Congress struck another careful compromise when it wrote the bill: it crafted the boards' composition to balance different regional and economic interests. To ensure regional representation, Congress directed that the nation be divided into Federal Reserve Districts and within each, a Reserve Bank be established whose directors consisted of residents of that region. The Act mandated that the Class A and B directors hold jobs within their district, while the three Class C directors were required to have been residents of the district for at least two years. Congress also further split the Class A directors into three types to represent member banks by size, which ensured that large, medium, and small banks had equal representation. And to ensure balance of different commercial interests, Congress mandated that the Class B directors be "actively engaged in their district in commerce, agriculture, or some other industrial pursuit."

Finally, a key goal of the Fed's founders was establishing a central banking system that kept the value of the dollar stable. The Act's authors understood that political pressures and private interests might push the value of the dollar down or up, and they feared both inflation and deflation. Accordingly, numerous features of the Federal Reserve System — such as its regional structure and the requirement to back Federal Reserve notes by either short-term bank loans or gold — were designed to insulate decisions about discount rates and the volume of notes in circulation from undue political and business pressures. Such checks against political influence were also incorporated into the Reserve Bank boards — for example, their prohibition of senators or representatives in Congress from serving as a director or officer of a Reserve Bank.

"Science" versus "Democracy"

The origins of the governance model go back to the Fed's founding in 1913, when lawmakers were bitterly divided over the central bank's purposes and functions. The political momentum for a central bank had accelerated after the Panic of 1907, but Congress struggled to resolve differences among those who wanted a regional, confederated structure and those who wanted a powerful central bank. Lawmakers from agricultural states pressed their interests, as did those who came from states active in mining and manufacturing. This was a debate about diversity, but one centered on addressing disparate state, commercial, and regional interests. More broadly, these early divisions reflected the fundamental schisms of that era: "democratic" populism versus "technocratic" progressivism, urban versus rural interests, small versus big banks, and regionalism versus federalism.

How did this effort begin? Central banks were well-established in Europe, but among early American political leaders, the very idea of central banking was deeply controversial, as the demise of the First and Second Banks of the United States showed. This resistance began to change with a series of banking crises in the Gilded Age, capped by the Panic of 1907. Leading figures in finance began to work with like-minded lawmakers on creating a more stable banking system. In 1908, Congress passed the Aldrich-Vreeland Act, which established a National Monetary Commission to study other central banks and recommend a solution. The chairman of the commission, Sen. Nelson Aldrich, a Republican from Rhode Island, convened a small working group to draft the commission's final recommendation, leading to a secret conclave on Georgia's Jekyll Island in 1910 that included Warburg and Treasury official Abram Piatt Andrew. This effort led to the release in 1912 of the Aldrich Plan, the predecessor of the Federal Reserve Act.

The Aldrich Plan envisioned a National Reserve Association that had both "scientific" and "democratic" components. The "scientific" elements included technocratic proposals the Jekyll Island group saw as necessary for a central banking system to be effective, such as the authorities to provide an elastic currency and serve as a lender of last resort in panics. The "democratic" elements, meanwhile, were intended to address populist concerns that this new national bank would an all-powerful, centralized entity. One way to do this was to distribute power across states, sectors, and regional interests by establishing local reserve associations. These local groups would in turn be organized into district associations. Each district would contain a branch of the National Reserve Association. Local associations would elect their own local boards of directors, which in turn would elect members of the district and national boards. In the local and district boards, bank-elected directors would make up the majority of the leadership, and voting rights would be weighted in favor of larger banks. By contrast, the central body in Washington, D.C., was to be a relatively weak board made up of forty-six members, only six of whom the federal government would select. After its release, reception of the Aldrich Plan was mixed. Banking groups warmed to the plan, but many Democrats viewed it as tilted toward Wall Street. Meanwhile, the burgeoning Progressive movement was generally hostile to Aldrich and wanted a banking reform plan with far greater public accountability.

Early Compromises

As this debate raged on, the Democrats swept the 1912 election, sending Woodrow Wilson to the White House. Proponents of banking reform expected they would have to start from scratch, but in a surprise move, Wilson championed their cause. He delegated the drafting of the new bill, the Federal Reserve Act, to two Democratic allies, Rep. Carter Glass of Virginia and Sen. Robert Owen of Oklahoma. A finance professor, Henry Parker Willis, provided much of the technical expertise in the drafting of the House bill. Glass was among those Democrats who wanted a regional model with power spread out among as many as twenty Reserve Banks and no central coordinating board at all. Wilson, helped by Owen and more like-minded allies in the Senate, sought a central board and a greater federal role.

Ultimately, the Federal Reserve Act represented a collection of compromises that tried to bridge these divides. But on net, the "democratic" side won some substantive provisions. The bill called for a network of powerful Reserve Banks (ultimately numbering twelve, reduced from the twenty Glass had proposed) that were largely autonomous. They could set their own benchmark lending rates and select which banks to lend to, and they held their own gold stock. The director classifications were set up to ensure occupational "diversity" among directors, while all nine had a vote in appointing their Reserve Bank chief executive officer, then known as a governor, now called the president. Even though the central body in Washington, called the Federal Reserve Board, appointed the Class C directors, the bill required that they live in their Reserve Bank district.

The "scientific" camp secured some concessions as well. Wilson got his Federal Reserve Board, staffed by U.S. presidential appointees, with two executive branch officials, the Treasury secretary and the comptroller of the currency. But the Board's main role was that of a loose oversight body, and it lacked the power to conduct credit or monetary policy on a national basis. In fact, the most dominant national official in the early years was the leader of the New York Fed, Benjamin Strong, also an important early backer of the Aldrich Plan.

This early arrangement reflected the widespread view that the Reserve Banks' primary role was to ensure stable monetary conditions in their districts. The governors who led the Banks came from finance and business backgrounds, and the chief Bank functions were issuing cash and, later, clearing checks. The Reserve Banks also served as lenders of last resort through their discount windows, and they could decide which securities to buy or sell and at which price. In short, through their power in conducting open-market operations and setting a District-wide credit policy, the Reserve Banks had far more control than the central board over monetary policy, a subject that was little understood at the time. But in a speech at Harvard in 1922, Strong noted the importance of these authorities.

"There is ... one function of the Reserve System the importance of which cannot be over-emphasized," he said. "It is, in fact, the heart of the System upon which the operation of every other part depends. I refer to the entirely new element which was super-imposed upon our banking System in 1914 by the establishment of the Reserve Banks, which were given the power to influence or to regulate or to control the volume of credit. Every other function exercised by the Reserve Banks sinks into insignificance alongside of the far reaching importance of this major function."

Strong also underscored the importance of the Fed's public function — and its inherent relationship to the elected officials of the U.S. government. "The Federal Reserve System has always impressed me as being essentially a social institution," he said. "It is not a super-government, it is simply the creature of Congress, brought into being in response to a public demand. It was not created only to serve the banker, the manufacturer, nor the merchant, nor the Treasury of the United States. It was brought into being to serve them all."5

An Early Test for the Fed

The shortcomings of this system became apparent in the early years of the Depression. Faced with a wave of bank failures, the Reserve Banks were unable to unite around one common policy. Some officials believed in the "real bills" doctrine, which held that the Fed should act procyclically (that is, curtail lending and tighten liquidity during downturns). Others sought a countercyclical approach that boosted liquidity by cutting the discount rate and lending permissively. What this meant was that Reserve Banks took different responses in 1929-32 to extending credit, expanding the monetary base, and acting as lenders of last resort. This led to divergent economic outcomes across the nation. In a 2009 paper that compared bank failures in southern and northern Mississippi, a split-district state, researchers found a significantly lower rate of bank failures and a much milder recession in the southern half of the state, reflecting the Atlanta Fed's aggressive actions as a lender of last resort. By contrast, the northern half, which was under the St. Louis Fed, saw much less aid to banks beset by runs and fared worse.6

The Fed's inability to use its tools effectively and to pursue unified policy to counteract the Depression is now a well-known lesson. But this failure also produced the reforms that led to the structure of the far more centralized modern Fed. The most important was the 1935 Banking Act, which established the modern structure of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), taking over the monetary-policy and credit-policy powers previously held by Reserve Banks. The Federal Reserve Board was renamed the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and it received enhanced powers to set bank reserve requirements, the discount rate, and interest rates for member-bank deposits.7 Furthermore, the Treasury secretary and the comptroller of the currency lost their seats on the Board, helping set up a wall between the Fed and the executive branch that was cemented with the Fed-Treasury Accord of 1951. A more centralized and effective central bank emerged.

As for the Reserve Banks, they lost their exclusive authority to select their own chief executive officers, as the Board was given the power to veto appointments as well as renew them every five years. The Reserve Banks' CEOs, the "governors," were demoted and renamed "presidents." While still an important position, this job now required collaboration over national monetary and credit policies with the Board of Governors in Washington — for example, by setting up a voting rotation for presidents on the FOMC and allowing them, voting or not, to participate in all policy meetings. Congress also slashed the pay of the Reserve Bank board chairmen. In short, after the challenges of the Great Depression, Congress altered the Fed's governance model, moving away from the regional system established in 1913 to become a more centralized organization.

Checks and Balances

While the FOMC's creation reduced Reserve Bank directors' roles in crafting monetary and credit policy, they have continued to perform many of the functions that the Fed's founders envisioned. One of their most important tasks is to select, supervise, and advise their Bank's CEO, whose title, since the 1935 Banking Act, has been president. In the Fed's early decades, the presidents were drawn mostly from banking, business, and sometimes law. Starting in the 1960s, however, Ph.D. economists began filling the ranks of presidents, as Reserve Banks built up their own research departments with trained academic economists to assist the presidents. In 1940, for example, nine of the twelve presidents were bankers and three were lawyers; none were economists. By 1980, eight of twelve were Ph.D. economists, a ratio that has largely continued to this day.8

Reserve Bank boards of directors also tend to select presidents who favor keeping the value of money stable, rather than risking inflation or deflation in hopes of attaining other policy goals. A 2014 study by Daniel Thornton and David Wheelock, both from the St. Louis Fed, documented this pattern. They found that since the creation of the FOMC, bank presidents dissented from the committee's decision 180 times in favor of tighter (less inflationary) policy and thirty-five times in favor of looser (more inflationary) policies. Members of the Board of Governors, in contrast, dissented only sixty-nine times in favor of tighter policy and 125 times in favor of looser policy. Overall, presidents accounted for 72 percent of all dissents in favor of less inflationary policies, while governors accounted for 78 percent of all dissents in favor of more inflationary policies.9

Allan Meltzer's research on the causes of inflation in the 1970s helps to explain this difference between members of the Board of Governors and Reserve Bank presidents. In a 2005 essay, he argued that "politicians elected for four- or five-year terms put much more weight on employment — jobs, jobs, jobs — than on a future inflation." Politicians have tended to select members of the Board of Governors whom they think have beliefs aligned with their own. And politicians have sometimes pressured members of the Board of Governors to adopt policies aligned with their short-term interests. These pressures often have fallen directly on the chair of the Board of Governors. For example, in the 1960s and 1970s, Fed Chairmen William McChesney Martin Jr. and Arthur Burns were pressured to limit anti-inflation efforts by Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, respectively. Burns, in particular, felt he had to acquiesce, at least to some extent, so that he could also remain an economic advisor to Nixon. By contrast, presidents of Reserve Banks may have felt less political pressure because they have reported directly to their boards of directors, composed of businessmen and community leaders who typically took a longer-term view of the economy's economic health than politicians running for reelection.10

The Modern Fed

Although many core features of the Reserve Bank governance structure date back to 1913, it has seen substantial changes as well. Some of those came in the 1970s, at a time when the Fed's reputation, more generally, was suffering during the Great Inflation. Amid concerns over conflicts of interest at certain Banks, Congress conducted a probe in 1976 that included a review of Reserve Bank board minutes, which led to a set of proposed reforms. This push contributed to the 1977 Federal Reserve Reform Act, best known for establishing the dual mandate that the public is familiar with today. But it also expanded the scope of a federal conflicts-of-interest statute to include Reserve Bank employees, officers, and directors. This statute makes it a crime for a director, officer, or employee of a Federal Reserve Bank to participate in a matter in which, to his or her knowledge, he or she has a financial interest.11

Moreover, Reserve Banks have had a long-standing practice, which the Board formalized as policy in 2011, of not providing directors with confidential supervisory information. Class A and Class B directors who are affiliated with thrift holding companies supervised by the Federal Reserve may not participate in matters such as approving the supervision and regulation department budget and the selection, appointment, or compensation of officers with responsibility for supervision and regulation.

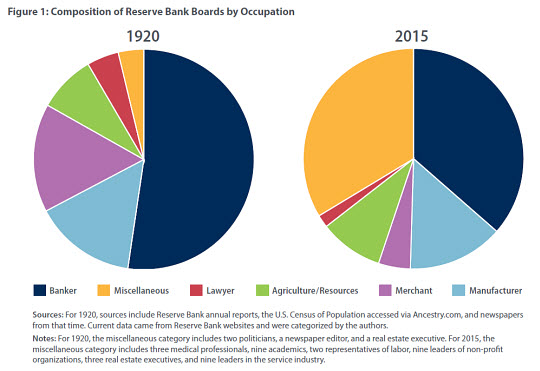

The 1977 reform was significant in other ways. It amended the Federal Reserve Act's rules about the Reserve Banks' boards of directors, requiring that all directors be appointed "without discrimination on the basis of race, creed, color, sex, or national origin." And notably, it expanded the pool of potential directors on boards beyond the sectors outlined in the 1913 Act of agriculture, commerce, and industry. Under the new provision, the Class B and Class C directors were to be elected "with due but not exclusive consideration to the interests of agriculture, commerce, industry, services, labor, and consumers." A comparison of the entire population of directors from 1920 to today, in fact, shows that the percentage with formal banking affiliations has dropped from 52 percent to 36 percent, with a more diverse occupational mix — nonprofits, academia, medicine, and services — making up most of the difference. (See Figure 1 below.) The academics include presidents, chancellors, and professors at major public and private universities. The nonprofit representatives include senior executives from the United Way, Goodwill, and Habitat for Humanity.

The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 was the most recent reform of Fed governance, as part of a much more sweeping overhaul of financial regulation. One of its consequences was taking away the power of Class A directors (and certain Class B directors) to vote in the selection of Reserve Bank presidents on grounds that member banks should not have a direct say in selecting an official who influences when and how they can receive assistance from their lender of last resort. This measure addressed, in part, public anger at the New York Fed and its central role in bailing out Bear Stearns and American International Group in 2008. In the years preceding that crisis, then-President Tim Geithner recruited board directors from Lehman Brothers (Dick Fuld), JP MorganChase (Jamie Dimon), and Goldman Sachs (Steve Friedman). Fuld resigned just before Lehman collapsed in September 2008, while Friedman resigned from the New York Fed's board in 2009 after news broke that he bought Goldman Sachs stock during the crisis (technically while in compliance with Fed rules at the time).12

"The New York Fed president is often viewed as a servant of the financial establishment, in part because the optics of the institution's governance are awful," wrote Geithner in his memoir, Stress Test. "I made some changes to the board that unfortunately made those bad optics even worse."13

Since the Board of Governors enacted the changes in the Dodd-Frank Act, however, Class A directors (as well as Class B directors affiliated with thrift holding companies) may not participate in most aspects of the appointment process of Bank presidents and first vice presidents. This means they do not serve on the search committees for the president and first vice president or take part in the committees' deliberations about the candidates, nor do they vote for a president or first vice president, including voting for reappointment.

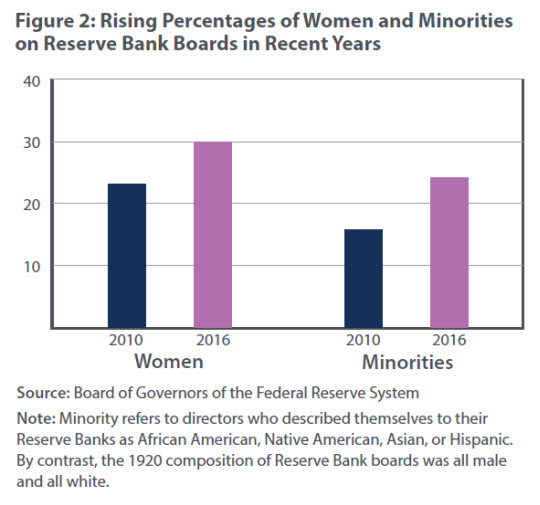

Meanwhile, the Dodd-Frank reforms have coincided with changes that have been less visible to the public eye, including a jump in the representation of women and minorities on Reserve Bank boards. Since 2010, minority representation has increased from 16 percent to 24 percent among Reserve Bank boards, including branch boards, while the share of women has risen from 23 percent to 30 percent. (See Figure 2 below.) As for the Federal Reserve System more broadly, in 2015 staff at the executive senior level was 18 percent minority and 37 percent female.14 The Dodd-Frank reforms included a provision creating an Office of Minority and Women Inclusion across all banking agencies, as well as at each Reserve Bank. Moreover, the Fed has launched an interdisciplinary effort to focus on all initiatives that relate to diversity and financial inclusion, from hiring to community development to credit access, which Fed Chair Janet Yellen noted in congressional testimony in June.15

A common thread among Fed critics is that a reformed Fed, with a more diverse composition and a broader balance of interests among its boards, would act more boldly to help those who have struggled the most economically. This particular debate no doubt will continue as the Fed continues to weigh plans to tighten interest rates and unwind its balance sheet as the economy recovers. Many economists argue, however, that monetary policy alone is not a sufficient or particularly well-designed tool to address inequality, which primarily stems from structural changes relating to globalization, technological change, demographics, and labor markets. As former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke wrote last year, the effects of monetary policy on inequality are "almost certainly modest and transient" in contrast to these long-term factors. For their part, he added, policymakers should look to "other types of policies to address distributional concerns directly, such as fiscal policy (taxes and government spending programs) and policies aimed at improving workers' skills."

"Policies designed to affect the distribution of wealth and income are, appropriately, the province of elected officials, not the Fed," he added. "Alternatively, if fiscal policymakers took more of the responsibility for promoting economic recovery and job creation, monetary policy could be less aggressive."16

Helen Fessenden is an economics writer in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Gary Richardson served as the Federal Reserve System historian from July 2012 to July 2016 and currently is a professor of economics at the University of California, Irvine.

See Mark Calabria, "Yes, the Federal Reserve Has a Diversity Problem," Blog posting on Alt-M: Ideas for an Alternative Monetary Future, June 23, 2016.

See Paul M. Warburg, The Federal Reserve System: Its Origins and Growth, Vol. 1, New York: Macmillan Company, 1930. The quotes cited here are on pages 22, 50, and 122, respectively.

See the 1914 Annual Report of the Federal Reserve Board, pp. 7-8, which notes that "tested banking experience" should apply to the two "Federal Reserve agents" who were Class C directors.

The Federal Reserve required member banks to pay in their initial capital over time. Capital that was paid in exceeded $54 million in May 1915 and remained over this level through the rest of the year. In December 1915, capital paid in stood at $54,915,000. See 1915 Annual Report of the Federal Reserve Board, p. 46.

See Benjamin Strong, "Address Made before Students of Graduate College," Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., November 23, 1922.

See Gary Richardson and William Troost, "Monetary Intervention Mitigated Banking Panics during the Great Depression: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from a Federal Reserve District Border, 1929-1933," Journal of Political Economy, December 2009, vol. 117, no. 6, pp. 1031—1073. A working paper version is available online.

Prior to the Banking Act of 1935, Reserve Banks had to receive approval from the Federal Reserve Board to change their discount rate, but the Board could not compel Reserve Banks to change their rate. The Board received that power from the Banking Act of 1935.

See Betty Joyce Nash, "The Changing Face of Monetary Policy," Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Region Focus, Third Quarter 2010, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 7-11.

See Daniel L. Thornton and David C. Wheelock, "Making Sense of Dissents: A History of FOMC Dissents," Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Third Quarter 2014, vol. 96, no. 3, pp. 213-228.

See Allan H. Meltzer, "Origins of the Great Inflation," Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, March/April 2005, vol. 87, no. 2, part 2, pp. 145-175.

See 18 U.S. Code § 208. This change in the 1977 Act specifically brought Fed employees, officers, and directors within the scope of the existing federal conflicts-of-interest statute, which had previously applied only to federal employees.

The New York Fed applied for and received a waiver from the Board in January 2009 to allow Friedman (a Class C director) to stay on the Reserve Bank board after Goldman Sachs was converted to a bank holding company in fall 2008. Because he owned Goldman stock at the time and bought more shares during the crisis, Fed rules would otherwise have required him to step down. The waiver brought him into compliance, but Friedman stepped down from the New York Fed in spring 2009 anyway. Scott Alvarez, general counsel to the Fed Board of Governors, told the Wall Street Journal at the time that Friedman was needed during the New York Fed's transition and that the conversion of Goldman into a bank holding company was "outside his control." See Kate Kelly and Jon Hilsenrath, "New York Fed Chairman's Ties to Goldman Raise Questions," Wall Street Journal, May 4, 2009.

See Timothy F. Geithner, Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises, New York: Crown Publishers, 2014, pp. 88-89.

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, "Report to the Congress on the Office of Minority and Women Inclusion," March 2016, p. 4.

Hearing on the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress, 114th Cong. (2016) (testimony of Janet Yellen, Chair of the Federal Reserve System Board of Governors).

See Ben S. Bernanke, "Monetary Policy and Inequality," Blog posting, Brookings Institution, June 1, 2015.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.