A Closer Look at Japan's Rising Consumption Tax

Japan plans to raise its national consumption tax next week from 8 percent to 10 percent. Some commentators and economists have blamed previous consumption tax increases for causing recessions in 1997 and 2014, but little statistical analysis has been published to support or refute such claims. This Economic Brief highlights new evidence that significant changes in Japan's household consumption behavior did in fact coincide with the 1997 tax hike.

Japan rose from the ashes of World War II and built one of the largest economies in the world by 1970. Its booming exports of automobiles and consumer electronics prompted some prognosticators to predict that the Japanese economy eventually would surpass the American economy.1

Japan's phenomenal GDP growth slowed somewhat in the 1970s and 1980s, but by 1990, the nation's real estate and stock market valuations had soared to previously unthinkable heights. At one point, a three-square-meter parcel of land in downtown Tokyo reportedly sold for $600,000.2 But the lofty market prices plummeted in the early 1990s, precipitating a financial crisis, a prolonged slowdown in Japan's real economy, and a steady slide into many years of deflation or near-zero inflation.3

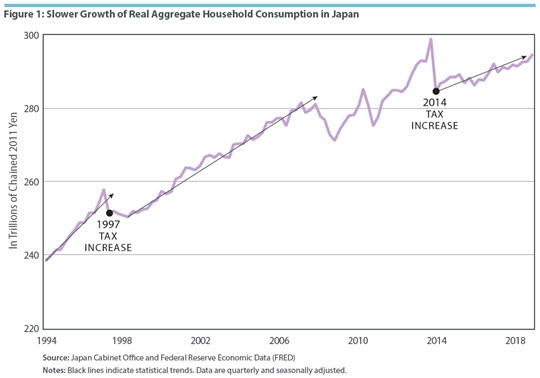

The government responded with numerous rounds of fiscal stimulus, and the Bank of Japan reduced the uncollateralized overnight call rate (its policy interest rate) from 6 percent in 1991 to 0.5 percent in 1995. The economy seemed to be recovering nicely until the government boosted the national consumption tax from 3 percent to 5 percent in 1997. This abrupt and largely unanticipated change in policy induced a small spike in consumption ahead of the tax hike, but after the tax increase, household consumption decreased and remained flat for two years. (See Figure 1 below.)4 Significant growth resumed in 1999 at a much slower pace, but it plummeted during the global financial crisis and again in 2010. Household consumption surged in 2013 after the government announced two more consumption tax hikes — to 8 percent in 2014 and to 10 percent in 2015.

The 2014 increase occurred on schedule, but the 2015 increase was postponed — until now.

A Closer Look at Consumption

To bring more rigorous statistical analysis to the long-running debate over Japan's consumption tax, one of the authors of this Economic Brief (Lubik) has studied the dynamics of consumption, the real interest rate, and measures of labor input in Japan from 1985 through 2013.5

Lubik and Jonathon Lecznar of Boston University analyzed comovement patterns of macroeconomic aggregates, conducted structural break tests, and employed generalized method of moments (GMM) estimations on structural Euler equations for consumption growth. They found that the behavior of aggregate household consumption and its relationship with real interest rates did indeed change considerably in the second quarter of 1997.6 The consumption tax increase from 3 percent to 5 percent in April 1997 coincided with a substantial decline in consumption growth, and the Bank of Japan's target interest rate reduction to 0.5 percent in 1995 (essentially to zero by 1999) coincided with a decline in the real interest rate.

Lubik and Lecznar explain these changes in terms of a simple model represented by the so-called Euler equation, which explains how consumption choices change over time and which is derived from a household's utility-maximization problem. A household and its members want to smooth consumption over time. This goal can be accomplished, for instance, by investing in interest-bearing assets that deliver returns to sustain household consumption when other sources of income decline. Therefore, the optimal intertemporal consumption choice depends on the effective real rate of return on the interest-bearing assets. In addition, consumption growth depends on habit preferences, where consumption smoothing also preserves past levels of purchasing.

Using various statistical methods, the authors find little evidence of habit formation from 1986 through the first quarter of 1997. However, starting in the second quarter of 1997, they find strong evidence of the presence of habits. The evidence of a greater responsiveness of consumption growth to real interest rate fluctuations also appears in the second quarter of 1997. But after the Bank of Japan's policy rate hit zero in 1999, consumption growth became less volatile and remained at a lower level.

In addition, various structural break tests clearly identify the second quarter of 1997 as the break point in household consumption.7 The date of this break "aligns ominously" with the April 1997 consumption tax hike, suggesting the possibility that the policy change induced the break. The researchers' GMM estimation of the Euler equation compared with a benchmark GMM estimation of the Euler equation confirms their finding that the 1997 tax hike coincided with a break in household preferences.

Overall, Lubik and Lecznar conclude that Japanese households formed stronger habit preferences and exhibited greater sensitivity to real interest rate movements in the wake of the consumption tax hike. The higher degree of habit formation arose largely from households becoming less risk averse or equivalently from the elasticity of intertemporal substitution. In other words, consumers became more willing to buy sooner (ahead of the tax increase) in lieu of buying later (after the tax increase).

While all of these equations and statistical tests stop short of blaming the 1997 tax increase for turning a nice recovery into a nasty recession, they add statistical rigor to the correlation between the tax hike and Japan's long-term decline in consumption growth. They suggest that the timing of the tax increase was unfortunate at best.

No Easy Choices, No Single Solution

In hindsight, the decision to increase the consumption tax in 1997 may seem like an obvious misstep, but in the 1990s, household consumption growth was fairly robust, and Japan was looking for a way to get its burgeoning national debt under control. The combination of higher government spending, lower taxes, and flat output had boosted general government gross debt from 63 percent of GDP in 1991 to 107 percent of GDP in 1997.8

Unfortunately, the tax increase did not produce enough revenue to stem the tide, and gross debt soared to 229 percent of GDP in 2012. At that point, as stated above, the Japanese government announced plans for two more consumption tax increases — from 5 percent to 8 percent in 2014 and from 8 percent to 10 percent in 2015. The 2014 increase coincided with a spike in household consumption ahead of the increase and flatter consumption growth after the spike. The proposed 2015 increase was postponed twice, but now it seems certain for October 1. Japan's prime minister, Shinzō Abe, has declared that nothing short of "the global financial crisis triggered by the collapse of Lehman Brothers" will delay the tax increase this time.9

Clearly, there are no easy fiscal policy choices for Japan. To continue issuing public debt to cover substantial annual budget deficits, the people who purchase the bonds must continue to believe that the nation will have the ability to pay them back when the bonds mature. Economists call this concept the "intertemporal government budget constraint." Even though credit-rating agencies have downgraded Japan's debt, yields on Japanese government bonds have remained low and stable.10 This observation implies that the purchasers of the bonds — primarily Japanese citizens and companies (in the primary market) and the Bank of Japan (in the secondary market) — are not overly concerned at the moment. But there are new challenges on the horizon. Most notably, the Japanese workforce is shrinking, and the average age of its population is increasing rapidly. Productivity growth has remained low, and the economy seems to need both expansionary fiscal policy and expansionary monetary policy to sustain a modest recovery.11

The problem seems too big for any single solution.12 A recent survey of Japan's economy by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development endorsed the imminent consumption tax increase and recommended further incremental hikes.13 The report also recommended that the country expand its workforce by embracing immigration and encouraging greater participation among women. Other observers have suggested all of the above plus public pension reforms, reductions in public health expenditures, programs to promote larger families, and the sale of government-owned enterprises and other nonfinancial assets.14 Eventually, the intertemporal budget constraint may necessitate several of these policy actions, but additional consumption tax increases, against the backdrop of Lubik and Lecznar's research, would argue for further study of the relationship between tax policy and aggregate consumption dynamics. Specifically, policymakers need to know more about the extent to which consumption tax increases affect the behavior of households, especially in the United States, where private consumption is the backbone of the economy.

Time to Watch and Learn

The Japanese economy never did surpass the American economy, but once again, Japan has arrived at an economic crossroads well ahead of the United States. (Japan's financial crisis preceded the U.S. financial crisis by about eighteen years.) It would be difficult to advise Japanese policymakers on which combination of treatments would be most effective at this point, but the best advice for U.S. policymakers is clear — watch and learn. The Japanese economy is a valuable laboratory for observing various approaches (such as a national consumption tax) to dealing with a looming government debt crisis exacerbated by a baby boom generation that is leaving the workforce, living longer, and breaking the entitlement bank. Japan's present could become America's future.15

Thomas A. Lubik is a senior advisor and Karl Rhodes is a senior managing editor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Eamonn Fingleton, Blindside: Why Japan Is Still on Track to Overtake the U.S. by the Year 2000, Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1995.

Timothy Knight, Panic, Prosperity, and Progress: Five Centuries of History and the Markets, Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2014, p. 284.

Some economists have blamed Japan's economic slowdown on low productivity growth rather than a breakdown in the financial system. See Fumio Hayashi and Edward C. Prescott, "The 1990s in Japan: A Lost Decade," Review of Economic Dynamics, January 2002, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 206–235.

Consumption data come from the Japan Cabinet Office via Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED).

Jonathon Lecznar and Thomas A. Lubik, "Real Rates and Consumption Smoothing in a Low Interest Rate Environment: The Case of Japan," Pacific Economic Review, December 2018, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 685–704.

The authors also find evidence of a structural break in the behavior of employment and hours worked that occurred earlier in the decade.

Specifically, the sequential Bai and Perron test to determine the number of breaks in the data indicates only one break over the entire sample period. The global financial crisis did not qualify, but the second quarter of 1997 did. This result supports the notion that the break in consumption was caused by policy choices as opposed to economic forces. The Andrews test for a single unknown break point also flags the second quarter of 1997. To assess this finding's robustness, the authors perform a standard Chow test for a range of known break dates around this period. Again, the second quarter of 1997 emerges as a break point.

Calculations of general government gross debt are from the International Monetary Fund via Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED). Japan's gross debt is substantially larger than its net debt, defined as gross debt minus financial assets that correspond to debt instruments. By that definition, net debt to GDP was 19 percent in 1991 and 42 percent in 1997. See Tanweer Akram, "The Japanese Economy: Stagnation, Recovery, and Challenges," presentation to the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, Atlanta, January 5, 2019.

Satoshi Sugiyama, "Abe Sticks with Plan To Raise Japan's Consumption Tax Despite Weak Tankan Results," Japan Times, July 1, 2019.

See Tanweer Akram and Anupam Das, "The Determinants of Long-Term Japanese Government Bonds' Low Nominal Yields," Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 818, October 2014.

See Ben S. Bernanke, "Some Reflections on Japanese Monetary Policy," presentation at the Bank of Japan, May 24, 2017. Near the conclusion of the presentation, Bernanke says: "When central bank action on its own reaches its limits, then fiscal policy is the usual alternative. However, in Japan, even fiscal policy may face constraints, resulting from the high debt-to-GDP ratio that already exists in Japan. This leads, inevitably I think, to discussions of coordination between monetary and fiscal policy. There are many ways such coordination could be implemented, but the key elements of a possible approach are that (1) the government commits to a new program of spending and tax cuts and (2) the central bank promises to act as needed to offset any effects of the program on the path of Japan's ratio of government debt to GDP."

See Selahattin İmrohoroğlu, Sagiri Kitao, and Tomoaki Yamada, "Achieving Fiscal Balance in Japan," International Economic Review, February 2016, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 117–154.

See Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, "OECD Economic Surveys: Japan 2019," April 2019. Additional support for incremental consumption tax increases comes from Michael Keen et al., "Raising the Consumption Tax in Japan: Why, When, How?" International Monetary Fund Staff Discussion Note 11-13, June 16, 2011.

See the conclusion of Gary D. Hansen and Selahattin İmrohoroğlu, "Fiscal Reform and Government Debt in Japan: A Neoclassical Perspective," Review of Economic Dynamics, July 2016, vol. 21, p. 223.

Keen et al. (2011), p 18.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.