How Secondary Trade Affects Social Welfare in an Over-the-Counter Market

Key Takeaways

- Over-the-counter markets with secondary trade and an unfixed quantity of assets suffer from inefficiency stemming from a double-sided hold-up problem between consumers and intermediaries.

- The inefficiency cannot be resolved through bargaining power alone, since efficiency would require both intermediaries and consumers to have full bargaining power.

- A budget neutral tax/subsidy scheme could resolve this inefficiency and increase social welfare by up to 13.3 percent.

A vast amount of trade occurs in over-the-counter (OTC) markets, where assets like real estate, bonds, Treasurys and asset-backed securities are exchanged privately between buyers and sellers. Unlike traditional markets like the New York Stock Exchange, OTC markets require time to find potential trading partners, and prices are contingent on the preferences and bargaining power of parties in a trade.

Significant research has been dedicated to understanding the dynamics of OTC markets, but most work assumes that asset supply in the market is fixed. Generally, this is not the case. For instance, firms can issue more corporate bonds or build more housing provided there are gains from doing so. Thus, features of secondary market trade can increase demand for assets, increasing issuance in the primary market.

My (Nicholas') 2019 paper "Asset Issuance in Over-the-Counter Markets" — co-authored with Zachary Bethune and Bruno Sultanum — studies this dynamic. It models an OTC market featuring agents analogous to securities issuers, consumers and intermediaries. We show that this market's equilibrium cannot be socially optimal. This stems from a double-sided hold-up problem where both consumers and intermediaries fail to internalize the social value of their trades. A government could achieve efficiency by issuing a budget-neutral tax and subsidy regime, increasing social welfare in the market by up to 13.3 percent.

Model Setup

The paper's market environment has three types of agents:

- Issuers issue assets that provide a flow of dividends, and they gain utility only by selling assets to investors, which include both consumers and intermediaries.

- Consumers highly value the dividends of these assets and want to keep assets.

- Intermediaries do not value the dividends of assets enough to keep them, so they will only buy an asset to sell it later to a consumer.

Issuers meet randomly with investors on the primary market, and investors meet randomly with one another on the secondary market. They can trade if one has an asset and the other does not. To simplify the environment, both investor types can hold a maximum of one good at any time.1

Social Failures in the Over-the-Counter Market

We find that, without government intervention, efficiency is impossible in this market. The market planner — an external party to the market that cares about overall welfare — wants a socially optimal asset level in the market and values the surplus generated by all trades. In contrast, intermediaries only consider the value that trades generate for themselves, resulting in a problem.

At the time intermediaries purchase an asset from an issuer, they assess the value that a future trade would provide them. However, instead of considering the whole value of the trade, they consider only a fraction of the value (which would be the value of the whole trade minus the intermediary's bargaining power). This is because of a hold-up problem: The intermediary must make an upfront investment before meeting with consumers to trade. When trades occur, consumers can "hold up" intermediaries for a share of the gains from the investment, preventing intermediaries from capturing the investment's full value. Thus, when intermediaries assess purchasing assets, they consider only the fraction of the gains from the investment that they can capture.

The asset supply in the market depends on the intermediary's valuation of assets, because intermediaries will only buy assets (and, thus, issuers will only issue them) if the value they gain from selling them is greater than the price. Since the planner cares about the full value of trades and the intermediary only cares about its gains, intermediaries will always purchase fewer assets than the planner wants. The only time the quantity of assets purchased matches the planner's desired level is when the intermediary has full bargaining power, capturing the full gains of their investment.

There is a similar problem with the consumer. The planner knows that consumers will, at some point, meet with intermediaries and potentially make purchases, generating a surplus. When consumers purchase assets directly from issuers, however, they can no longer purchase from intermediaries. The planner considers the full value of this loss. Consumers also account for this loss while deciding whether to buy issuers' assets, but they only care about their lost value. Again, this is because of a hold-up problem: When consumers forgo purchasing from issuers, they are making upfront investments — the loss of not having an asset — before they meet with the intermediary to bargain. When the trades occur, intermediaries capture a portion of the gains from the consumers' investment.

Thus, the consumers' loss associated with purchasing from issuers will always be less than the planner's value of the loss unless consumers have full bargaining power. When they don't, consumers will buy too many assets (from the planner's perspective) from issuers, destroying surplus that could have been generated by purchasing from intermediaries.

Taking these two hold-up problems together, replicating the planner's solution requires two things:

- Intermediaries hold all bargaining power to fully consider the social value of buying from issuers to sell later.

- Consumers hold all bargaining power to fully consider the social value of waiting to buy from intermediaries in the future.

These two conditions can never be met simultaneously, so any distribution of bargaining power cannot be efficient.2

In a market with a fixed number of assets, these hold-up problems are not an issue: Asset prices may not reflect the social value of trades, but assets will filter from intermediaries to consumers, resulting in efficiency. When issuers create assets, however, mispricing influences the incentives for investors to purchase assets from issuers. When intermediary bargaining power is too high, investors overvalue assets, and asset supply is inefficiently high. When consumer bargaining power is too high, there is little benefit for intermediaries to buy and resell assets, so asset supply is inefficiently low.

Government Interventions

There are two policy interventions that could remedy the loss of social value caused by this double-sided hold-up problem.

Tax Structure

Taxes can be designed to ensure investors internalize the surplus of their trades:

- Subsidize intermediaries' asset purchases so they internalize the full surplus of an eventual sale

- Tax consumers' asset holdings so they internalize the full loss of not purchasing assets in the future3

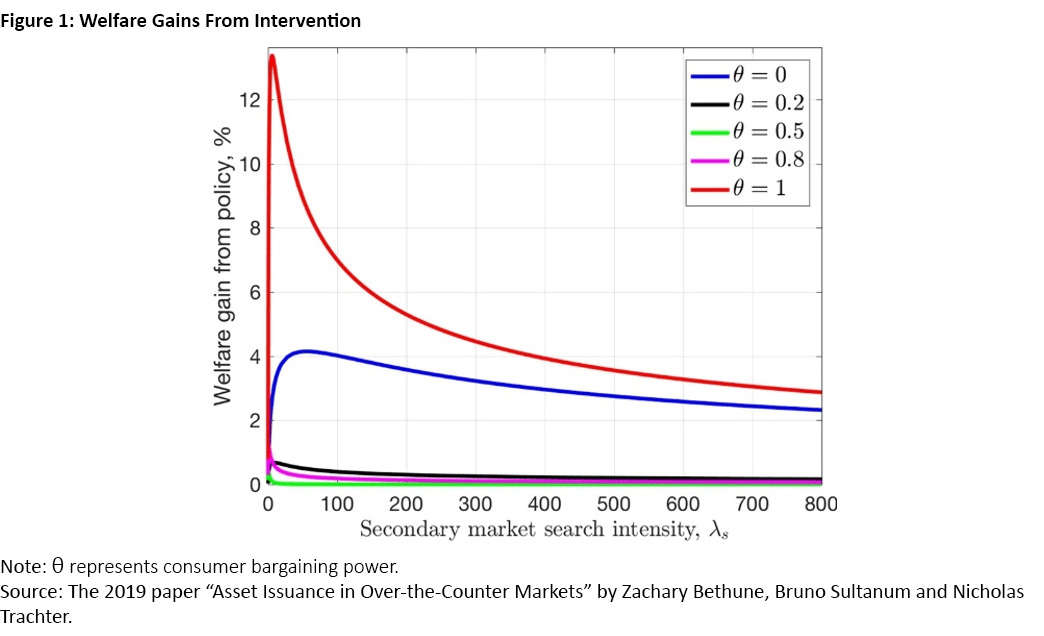

We use our model to test the impact of implementing this scheme, allowing for different levels of secondary market search intensity — the expected number of times an investor finds a trading partner over the course of a year.4 Figure 1 displays the effects of government intervention dependent on search intensity and consumer bargaining power.

The benefits of intervention are most pronounced at the extremes of bargaining power: When the consumer has full bargaining power, welfare gains from government intervention could be as high as 13.3 percent. When the intermediary has full power, welfare gains could be just above 4 percent.

Search intensity is another important factor in the efficacy of government intervention. Intervention is most effective in markets where trade is slow, but the double-sided hold-up problem ensures that a tax-subsidy scheme would increase welfare even when trading speed is extremely high, especially at the extremes of bargaining power.

Market Structure

A slight modification to the initial market structure — one that restricts the agents who can access the primary market — would also result in market efficiency. In some three-party markets, only intermediaries buy assets on the primary market (due to technological restraints, regulations or other barriers to entry), and consumers trade only on the secondary market. Because consumers no longer have access to the primary market, they become passive agents that will purchase assets from intermediaries regardless of who has buying power.

This is a solvable single-sided hold-up problem, with some level of buying power where consumers' utility from purchasing assets is the same as the social value of them having those assets. This market is efficient within its given structure, but it is not socially preferable to a market where all agents have access to the primary market: It is only mentioned as a potential OTC market where the double-sided hold-up problem would have no impact.

Conclusion

Using a three-party model, we describe the social inefficiencies that could emerge in an OTC market due to a double-sided hold-up problem, and we discuss the budget-neutral tax/subsidy scheme that could remedy these inefficiencies. While these results do not hold for all market configurations (for example, when not all consumers have access to the primary market), they demonstrate the need to consider the structure and regulation of OTC markets to maximize the social benefit that they provide.

Nicholas Trachter is a senior economist and research advisor, and Spencer Cooper-Ohm is a research associate, both in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

This simplification is obviously a large deviation from real-life markets, but the inefficiencies discussed in the remainder of the article still exist as long as investors have diminishing marginal returns to owning assets.

This result occurs in a framework in which it is assumed that issuers on the primary market have no bargaining power, but the same inefficiency occurs when that assumption is relaxed. A proof of this is available in the paper.

If revenue from taxation does not equal the cost of subsidies, lump sum taxation could be used to ensure a balanced budget.

In practice, the speed of trade varies depending on the type of asset being traded. The median time for a municipal bonds intermediary to secure a deal between two parties is five days, as noted in the 2007 paper "Dealer Intermediation and Price Behavior in the Aftermarket for New Bond Issues" by Richard Green, Burton Hollifield and Norman Schürhoff. The same process for securities takes 37 days, as noted in the 2017 paper "Bid-Ask Spreads, Trading Networks and the Pricing of Securitizations" by Hollifield, Artem Neklyudov and Chester Spratt.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Trachter, Nicholas; and Cooper-Ohm, Spencer. (December 2025) "How Secondary Trade Affects Social Welfare in an Over-the-Counter Market." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-46.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.