Caution: Pipeline Construction Ahead

It goes without saying that the shale oil and gas boom has had a transformative impact on the U.S. energy sector. After peaking in the 1970s, oil and natural gas production was expected to taper off as exiting stockpiles were slowly depleted. As a result of technology and new extraction methodologies, oil and natural gas production has taken off, and the U.S. is the leading oil and natural gas producer in the world.

U.S. oil production surpassed its previous decades-old high in 2017, and U.S. natural gas production surpassed its previous high seven years ago (and is currently 27 percent higher than its previous peak in 1973). Domestic oil production has grown such that foreign exports have become less necessary; the petroleum trade gap has shrunk considerably. Natural gas production exceeds domestic consumption and the U.S. is now a natural gas exporter. Terminals that were originally designed to receive imports of liquefied natural gas are being converted to allow for U.S. exports.

West Virginia is one of the states caught up in this energy revolution. Located on top of the Marcellus and Utica shale formations, West Virginia has seen a similarly striking change in energy production. Perhaps just one statistic underscores the dramatic change in West Virginia’s natural gas sector: Production rose by roughly 300 percent from 2011 to 2017. And in 2017, West Virginia was the ninth largest producer of natural gas in the U.S. Of course, this increase has been almost entirely due to shale gas production.

Given the increase in supply, natural gas consumption in West Virginia increased as well, up nearly 50 percent from 2011 to 2016 (coal remained the predominant energy source, however). Beginning in 2011, production outstripped demand and excess demand grew substantially as production continued to expand. So what to do with all that gas?

Here come the pipelines. In the first stage of the natural gas revolution, wells were put in at a tremendous pace (as demonstrated by the stunning increase in production), and it was assumed that at some point additional infrastructure would follow that would accommodate the additional volume as well as provide for additional outlets. That next stage is now well underway. West Virginia already has several thousand miles of interstate and intrastate natural gas pipelines traversing the state.

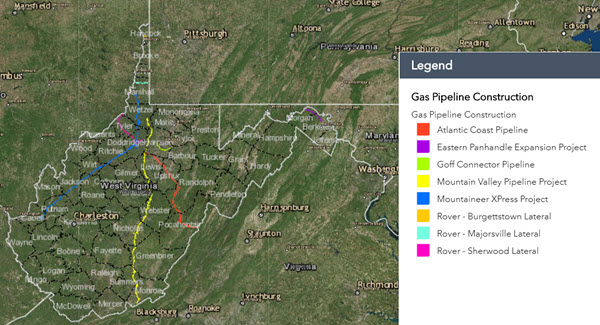

Those existing pipelines are set to be augmented by six new pipeline projects: the Mountain Valley Pipeline, Atlantic Coast Pipeline, Mountaineer Xpress Pipeline, Mountaineer Gas Company Eastern Panhandle Expansion Project, Rover Pipeline, and the Goff Connector Pipeline. These projects add over 600 miles of additional pipeline, but more importantly, they provide additional markets for West Virginia natural gas (see map below). Here is some detail on the larger projects:

- The Mountain Valley Pipeline will be approximately 303 miles in length and will run north-south through West Virginia and into southwestern Virginia where it will connect to another pipeline with access to the Mid- and South Atlantic regions. The pipeline will be capable of transporting at least 2 billion cubic feet (Bcf) per day of natural gas. Construction began in early 2018 with completion (with the pipeline in service) expected by year-end.

- The Atlantic Coast Pipeline will originate in north-central West Virginia and stretch in a southeasterly direction through Virginia and then south through North Carolina with a lateral to Chesapeake, Va., near Norfolk. All told, the pipeline will be roughly 600 miles in length and be capable of transporting roughly 1.5 Bcf per day. Construction began in early 2018 with completion expected by the end of 2019.

- The Mountaineer XPress project received final permitting approval in January 2018 and work on the compressor stations began shortly thereafter. The pipeline will originate in northern West Virginia (Marshall County) and run south to Wayne County, W.Va., and will include approximately 165 miles of new pipeline and will transport 2.7 Bcf per day of natural gas. The $2.1 billion project is the second largest (by volume) new pipeline project for the Marcellus-Utica region. Construction is expected to be completed in the fall of 2018.

With the amount of work to be undertaken to complete these projects, it is not surprising to see a sharp increase in employment growth in the construction sector. Payroll employment in the construction industry increased by 11.1 percent from May 2016 to May 2017, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) monthly survey of business establishments, and was up 14.7 percent for 2017 (December to December).

However, since peaking in December at 34,300 employees, payroll employment in the construction industry has been flat. It appears that most of the hiring to date took place prior to the start of the projects, perhaps once businesses received word on whether their bid was accepted or not. In addition, businesses have been reporting difficulty finding workers for some time now—particularly for workers with specific trade skills such as welding—so it’s plausible that these workers were scooped up early.

Not surprisingly, wages are rising in the sector as well. The BLS also produces employment data based on its Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) program, which contains employment and wages reported by employers and covers more than 95 percent of U.S. employment. Unfortunately, the QCEW are reported with a significant lag—the most recent data are for the fourth quarter of 2017. But because the data represent close to the entire universe of employees, the signals from the QCEW are very telling.

According to the most recent data, construction employment rose by 13.6 percent from the fourth quarter of 2016 to the fourth quarter of 2017, and the average weekly wage increased by 17 percent. As a result of the increase in employment and the increase in wages, total wages in the construction sector increased by 31 percent (from $425 million to $558 million) in 2017.

Have a question or comment about this article? We'd love to hear from you!

Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.