These posts examine local, regional and national data that matter to the Fifth District economy and our communities.

State Revenues Hit Hard by COVID-19

The negative impacts of COVID-19 on the U.S. economy have been staggering and are only just starting to show up in the economic data. After the government-ordered shutdowns went into effect in mid-March, we began to see an unprecedented rise in initial unemployment claims. Previous posts have discussed the changes made to unemployment insurance programs in Fifth District states by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) and have looked at how the sharp increase in initial claims data would precede other labor market measures, namely payroll employment and the unemployment rate. Since then, on May 8, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that just over 20 million jobs were cut in April and the unemployment rate rose from 4.4 percent to 14.7 percent, both of which were record-setting month-over-month changes. For some perspective, the 20 million jobs lost in a single month wiped away the gains that had accumulated over the preceding nine years.

Additionally, the Bureau of Economic Analysis recently released data on gross domestic product for the first quarter of 2020, which measured the contraction of the U.S. economy at an annual rate of 4.8 percent. This was a large negative swing from the fourth quarter of 2019, when the economy was growing at an annual rate of 2.1 percent. The main contributor to the net decline in the first quarter was personal consumption expenditures, particularly for spending on big-ticket items, such as motor vehicles, and for services in the industries that have been largely shut down, such as health care, food services (e.g. restaurants) and accommodations, and recreational services. Health care might stand out as an odd category to be down during a health crisis, but this is likely due to the limitations put on nonemergency procedures.

Having fewer people working and spending less on goods and services not only hurts the U.S. economy as a whole, but also negatively impacts state and local governments that depend on income and sales taxes as their primary sources of revenues. In fact, the National Association of State Budget Officers estimates that, on average, about 45 percent of state revenues in fiscal year 2019 came from income taxes and another 30 percent came from sales taxes. This, of course, varies by state.

The chart below shows the distribution of general fund revenues for Fifth District jurisdictions. Virginia is the most heavily dependent on income tax revenue, while the District of Columbia is the least dependent. In the District of Columbia, half of general fund revenues come from other sources, with property taxes being the largest other source. In North and South Carolina, about one-third of general fund revenues come from sales taxes.

Status of State Revenue Collections in the Fifth District

Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, state governments were generally in strong financial positions. According to NASBO’s most recent Fiscal Survey of States, many states experienced revenue surpluses in fiscal years 2018 and 2019 and used those surpluses to bolster rainy day funds. In fact, the median rainy day fund reached a record 7.6 percent of general funds in fiscal year 2019. And in addition to growing their rainy day funds, general fund spending was on the rise. Across all states, spending was up 5.8 percent year-over-year in fiscal 2019, and spending was expected to increase another 4.8 percent in 2020.

Revenue reports from February and March generally indicated that Fifth District states were on pace to end fiscal year 2020 at or ahead of revenue projections. For example, data from February for South Carolina showed revenue growth of 8.5 percent, which outpaced the projected 5.3 percent growth. Similarly, Virginia had projected that total general fund revenues for March would be 3.2 percent above 2019 numbers, but instead collections came in 6.6 percent higher. However, the March revenue report for Virginia specifically said that the March numbers did not reflect any issues from COVID-19, but that they would begin to show up in the April numbers. At the time of writing this article, figures for April were not available yet.

Despite the fact that Fifth District jurisdictions have yet to release revenue numbers that show a direct impact from the pandemic, each state and the District of Columbia has said that they are anticipating revenue shortfalls. Among those that have given estimates for the current fiscal year, North Carolina officials have projected a 3 to 5 percent expected revenue shortfall, while the comptroller of Maryland has warned state officials of a possible a 15 percent drop. Some state officials have also said that they expect continued shortfalls going into fiscal year 2021.

Dealing with Shortfalls: Pre-COVID-19

So what typically happens when state revenues fall short? Under normal circumstances, state budgets, unlike the federal budget, have to be balanced. That means that in the face of a revenue shortfall, a state has to do some combination of the following: cut spending, pull money out of their rainy day fund, or raise additional revenues through new taxes, fees, or by receiving additional funding from the federal government.

To date, there have been a few official statements from governors and budget officials recommending ways to address the shortfalls, most of which have focused on freezing any non-necessary spending. The governor of Virginia, for example, recommended that several allotments for discretionary spending be rescinded, some of which included pay increases for teachers and corrections officers. He also proposed cuts to community college funding and financial aid to state universities. Similarly, the governor in Maryland froze all non-COVID-19 related payroll spending, halted hiring for all vacant positions, and asked the department of budget and management to identify further budget cuts. In North Carolina and West Virginia, officials have stated that they are looking at ways to cut budgets but no specifics have been released yet.

As mentioned before, rainy day funds are available for states to fill budget shortfalls and have been growing to historic levels in recent years. However, even the largest rainy day fund among Fifth District jurisdictions (14.4 percent of general fund spending in West Virginia) might not be enough to cover the potential gaps. The revenue secretary in West Virginia said that the state could be facing a 10 percent shortfall in the current fiscal year that ends June 30, even though the economic shutdown only took hold in the final few months. He expects further lost revenue in the next fiscal year as well.

While it is not uncommon for states to receive federal funding for specific purposes, such as for public welfare, education, or infrastructure spending, the federal government does not generally provide direct revenue replacement for jurisdictions facing shortfalls. That fact did not change in the recent historic stimulus and relief packages passed by Congress. However, given the dramatic shortfalls in revenue coupled with the rising costs of responding to the public health crisis, Congress did include targeted financial assistance for states and local governments to use to alleviate the fiscal crunch caused by the pandemic.

Federal Government Assistance: CARES Act

In an effort to help state, local, tribal, and territorial governments meet the demands of the pandemic response, Congress included a $150 billion Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) as a part of the $2 trillion CARES Act. While other sections of the CARES Act included billions to boost existing grant funding and new spending to help the public education system meet their financial and educational challenges, the CRF is the primary vehicle for state and local governments to respond to the public health and economic impacts of COVID-19.

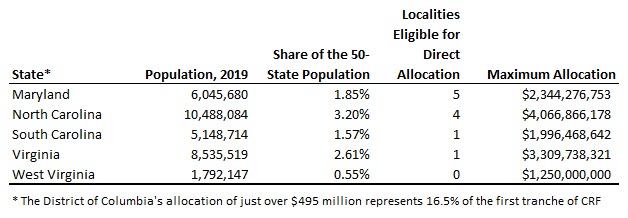

Within the $150 billion CRF appropriation, there are three different tranches of funds. The first is $3 billion set aside for payments to the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa, which is to be allocated in proportion to the share of the total combined population. The second is $8 billion set aside for tribal governments, allocated in proportion to tribal populations, with the smallest tribal populations receiving a minimum payment of $100,000. The remaining $139 billion is allocated to states at a rate proportional to their population, with a minimum allocation of $1.25 billion per state.

Local governments serving a population above 500,000 are eligible to claim a share of their state’s overall allocation and can elect to receive that share directly from Treasury, while smaller localities must rely on their state governments to share the funding. A local government claim on funding reduces the amount that goes to their state, creating a situation where a state with a higher number of large localities could have a substantial portion of their allocation diverted to cities and counties.

The CARES Act did not give recipients carte blanche to use their CRF allocation; it placed parameters on how governments can spend the money. The legislation stipulates that the CRF can only be used to cover costs that are necessary expenditures incurred due to the COVID-19 public health emergency; that were not accounted for in states’ most recent budget as of March 27, 2020; and that are incurred during the period March 1, 2020, through Dec. 30, 2020. The legislation, and subsequent guidance from the U.S. Department of the Treasury, target the funding toward only COVID-19-related expenses. Any unused funds must be returned to the Treasury.

As a top-line rule, recipients of CRF funding cannot use the money to fill shortfalls in government revenue, or otherwise replace revenue, to cover expenditures that do not otherwise qualify under the statues. Despite this limitation, CRF provides states with a good deal of flexibility in how they can use the money to meet pandemic-related needs, which will limit the amount of cuts to essential programs that governments will have to make in order to respond to the wide range of health, economic, and education challenges stemming from the pandemic.

According to guidance issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, recipients of CRF funds can use the money to cover the costs of directly responding to the pandemic, such as public health or medical needs and payroll for workers directly involved with virus response and mitigation, as well as second-order effects of the emergency, including providing economic support to unemployed individuals or businesses facing interruptions from government-ordered closures. For example, North Carolina recently passed the 2020 COVID-19 Recovery Act, which directs $1.6 billion of the state’s $4 billion CRF allocation to a wide range of eligible expenses. That legislation included:

- $50 million to purchase personal protective equipment and sanitation supplies

- $125 million in low-cost small-business loans

- $95 million for hospitals

- $44 million for online summer school for the University of North Carolina system

- $150 million for immediate distribution to local governments

- $9 million for rural broadband

While CRF will provide a substantial lifeline to state, local, tribal, and territorial governments, a prolonged economic slowdown will undoubtedly strain their resources. The National Governors Association has already called on Congress to provide an additional $500 billion in support to make up for revenue losses related to the pandemic. That idea has already become a point of contention between parties, as some members do not believe the federal government should be backfilling budgets for states they believe are not being well managed. There are also proposals in Congress to allow states greater flexibility in how they use existing funds from the CRF, including using CRF funds to replace revenue shortfalls. This is an ongoing debate within Congress and will continue to be a point of concern as legislators consider additional actions to combat the many effects of the pandemic.

Conclusion

From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, elected officials at all levels of government began to take dramatic steps to stem the spread of the virus. The shutdown measures are not without serious financial implications for state and local governments as they face major new response expenditures at the same time that they experience serious revenue shortfalls from a prolonged economic slowdown. While the federal government is providing some support for the added costs, states are still going to be left with lower revenues and tough decisions. Spending cuts seem inevitable to maintain balanced budgets, but details are still emerging on how state and local governments are going to adjust.

Have a question or comment about this article? We'd love to hear from you!

Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.