These posts examine local, regional and national data that matter to the Fifth District economy and our communities.

Unemployment Insurance Programs and the Role of the States

The ongoing economic crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic has caused many businesses to temporarily close or reduce staffing and hours, resulting in dramatic increases in unemployment. While this undoubtedly creates hardship for many individuals and their families, we do have “automatic stabilizers” that mitigate the impact for workers and for the economy.

Our unemployment compensation program—created by the Social Security Act in 1935—works counter-cyclically, paying out benefits during recessionary times and replenishing funds during recovery periods. Unemployment insurance helps to buffer individuals against shocks such as downturns within specific industries, or, as is the case today, much broader shocks to the economy. In other words, it provides income to back them up when they find themselves out of work through no fault of their own.

Today, we face unprecedented demand on our unemployment insurance infrastructure, as evidenced by recent historically high spikes in initial claims for unemployment insurance, described in some detail in yesterday’s post. This piece describes—at a high level—the workings of the unemployment insurance program, the role that states play, and the extraordinary programs that have been initiated by the federal government in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Unemployment Insurance Program in “Normal” Conditions

The unemployment insurance program is a federal-state partnership with certain requirements set by federal law, but with the states determining benefit structure and state tax structure as administrators of the program. Specifically, states take in claims from individuals, determine eligibility, and ensure timely payment of benefits to workers. States also determine employer liability and collect taxes. These delegated responsibilities allow for some variation across states. For example, most states pay benefits for a maximum of 26 weeks, but many states vary the number of weeks payable based upon the amount of earnings in the individual’s base period, which is usually calculated from four consecutive quarters of wages.

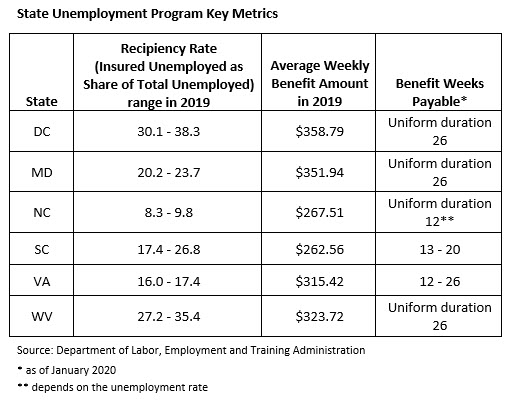

States also have differences in the average weekly benefit received by unemployment insurance recipients and the share of the total unemployed in the state that receive unemployment benefits (i.e., the recipiency rate). Within the Federal Reserve’s Fifth District (DC, MD, VA, NC, SC, and WV), the average weekly benefit in 2019 ranged from $262.56 in South Carolina to $358.79 in the District of Columbia, while the recipiency rate ranged from a low of 8.3 percent in North Carolina to a high of 38.3 percent in the District of Columbia.

All state laws require that certain conditions be met for benefit eligibility; these include that the applicant be able to work, available for work, and actively seeking work. These requirements are intended to make sure that applicants are attached to the workforce and that the benefits received will be supportive as they look for another job or await reemployment with their previous employer. I will come back to these requirements in the context of the COVID-19 crisis response.

Even in “normal” times, some regions of the country may experience high and rising unemployment, so federal law also provides for extended benefits (EB) —determined at the state level—which allow individuals to receive an extra 13 weeks, or 20 in some cases. The primary measure that determines if a state must “trigger on” to EB is the insured unemployment rate, which is the share of insured unemployed relative to total covered employment (i.e., number of employees reported as part of the UI program). It is mandatory for states to trigger on to EB when the insured unemployment rate for the previous 13 weeks is at least 5.0 percent and is 120 percent of the rate for the same 13-week period in the previous two years. There are also optional triggers that some states adopt to determine when they trigger on to EB and start paying for the additional 13 weeks of benefits. Normally, the cost of EB is shared evenly between the federal government and the state. As of April 4, 2020, no state had triggered on to EB.

Unemployment Insurance in Times of Crisis

Under extreme conditions, such as a severe downturn, the federal government may choose to establish new programs that lengthen the potential duration of benefits, expand access beyond those who would normally qualify for unemployment compensation, or increase the amount of assistance provided to unemployed individuals. During the Great Recession of 2007–2009, when unemployment continued to rise for nearly a year after the official end of the recession, special programs were created that increased the duration of unemployment benefits to unprecedented levels of as much as 99 weeks in some states. Researchers explored the impact of such extended unemployment benefits on the duration of unemployment spells (see Econ Focus).

The precipitous increase in unemployment resulting from the social distancing practices required to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, has given rise to a number of new guidelines and programs. In mid-March, the Department of Labor issued guidance to remind state workforce agencies of their flexibility in determining eligibility for benefits in light of the special circumstances of COVID-19 that might cause employers to cease operations, employees to be quarantined, or to care for family members who had been infected. This guidance was followed by additional support, through administrative grants, to state workforce agencies through the Emergency Unemployment Insurance Stabilization and Access Act of 2020 (EUISAA). The EUISAA also provided for full federal funding during extended benefit periods through December 31, 2020.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed by Congress on March 27, 2020, provided a range of economic stimulus measures to support various sectors of the economy and included significant relief for workers through the unemployment insurance program. Among the actions taken, temporary coverage was provided for individuals who have exhausted their entitlement to regular unemployment compensation as well as individuals who are not eligible, such as self-employed workers or those with a limited work history. In addition, the normal one-week waiting period was effectively waived, as the federal government plans to fund 100 percent of this cost for states. Perhaps most significantly, individuals collecting benefits through most unemployment compensation programs will receive an additional weekly payment of $600 for weeks of unemployment ending on or before July 31, 2020. For perspective, the average weekly benefit amount in the U.S. was just under $378 in the fourth quarter of 2019.

The key programs of the CARES Act and their provisions are summarized below:

- Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA)

Provides up to 39 weeks of benefits and is available starting with weeks of unemployment beginning on or after January 27, 2020, and ending on or before December 31, 2020. Covers individuals who are self-employed, seeking part-time employment, or who otherwise would not qualify for regular Unemployment Compensation (UC) or EB under state or federal law or Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC). Coverage also includes individuals who have exhausted all rights to regular UC or EB under state or federal law, or PEUC.

- Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC)

Provides up to 13 weeks of benefits to individuals who have exhausted regular UC. States must offer flexibility in meeting the “actively seeking work” requirement if individuals are unable to search for work because of COVID-19, due to illness, quarantine, or movement restriction. Covers weeks of unemployment through December 31, 2020, starting with date of signed agreement of the state agency and DOL.

- Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC)

Provides an additional $600 per week to individuals who are collecting regular UC, PEUC, PUA, EB, and payments through some additional programs. Available for weeks of unemployment through July 31, 2020, starting with date of signed agreement of the state agency and DOL.

States Managing Massive Influx of Applications

With economic conditions changing so swiftly and new programs quickly responding to the crisis, state workforce agencies have been overwhelmed with applicants almost overnight. Most states receive initial claims for unemployment insurance through their websites (see chart below), and as of early April, every state workforce agency in the Fifth District (and likely the country) displayed messages explaining that their systems were experiencing high volume and were having technical difficulties. Many individuals reported having trouble getting through as the application systems were overwhelmed. At one point, the centralized system that validates social security numbers was also unable to keep up with the demand. To help regulate the flow, Maryland’s Department of Labor requested applicants to apply according to their last name, with last names starting with A–F filing claims on Mondays; last names starting with G–N filing on Tuesdays; last names starting with O–Z filing on Wednesdays; and anyone filing online Thursdays through Sundays.

In addition to state workforce agencies working on their technical capacity to accept applications, they have also made changes to their systems to accommodate the new programs. For example, applicants that were previously ineligible for regular unemployment insurance—but now meet the requirements of the PUA—could not initially apply without being rejected, as changes were put in place to reflect updated eligibility requirements. Similarly, states needed to enter agreements and receive specific guidance before they could start issuing the $600 weekly federal PEUC, although all of the state agencies reassured applicants that they would be paid retroactively for all of the weeks for which they were eligible. Meanwhile, applicants can only be patient as programs more fully ramp up, systems catch up, and much needed funds make it to them.

State Workforce Agency Websites:

Virginia: http://www.vec.virginia.gov/covid19

Maryland: http://www.dllr.state.md.us/employment/unemployment.shtml

North Carolina: https://des.nc.gov/need-help/covid-19-nc-unemployment-insurance-information

South Carolina: https://www.dew.sc.gov/covid-19-resources

West Virginia: https://workforcewv.org/covid19

District of Columbia: https://does.dc.gov/page/ui-benefits-claimants

Have a question or comment about this article? We'd love to hear from you!

Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.