Whose Land Is It? Heirs’ Property and Its Role in Generational Land Retention

The U.S. economy — like many modern economies — is built on the premise of clearly delineated property rights. When it comes to land or homes, clear ownership is generally required to secure a loan for property improvements or qualify for a government grant after a disaster. Property ownership has also been a way to build wealth both within and across generations. Heirs’ property occurs when property is transferred from one generation to the next without estate planning or a clear will with a line of ownership, and it can be an impediment to both the current and future economic trajectories of those who live on the property.

Property loss has contributed to creating and widening the wealth gaps that have existed in our nation since its inception. Heirs’ property has been one definable way that this loss — in some cases theft — has occurred. For example, scholars who have studied heirs’ property have argued that it has contributed to the racial wealth gap we experience today. In the Fifth District, and in much of the South, this problem of heirs’ property has resulted in substantial loss of both wealth and land and has hampered economic opportunity for many families.

The Challenge of Heirs’ Property

Imagine this: One couple with four children purchases 100 acres of land in 1910. Each child has children, and each grandchild has children. Some subset of the family stays on the land and many children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren move away. Each time a generation passes away, the land stays with the descendants living on the land, and the title remains in the name of the original buyers. By 2020, there could be 30 or 40 (or more) living descendants, all of whom — regardless of their physical/financial investment in the land or their living distance from the land — have the same rights to the 100 acres purchased in 1910. The lack of property title will limit the ability of those who are living on and maybe even working the land to access credit, sell natural resources, or participate in land improvement programs.

This 100 acres is the definition of heirs’ property, also referred to as tenancy in common. In addition to creating barriers (e.g., credit access), heirs’ property is more susceptible to legal forfeiture or sale. Partitioning is a legal method that allows tenants to exit this fractional land ownership. However, heirs that do not intend to sell their land can lose it through a certain type of partition (i.e., partition sales) for two reasons: (1) Any tenant in common can request to partition; and (2) If partition is requested, any tenant in common can request — or a judge can order — that the entire property is sold at auction. Therefore, if one heir sells their share of the property to a developer, for example, that developer can request to auction the entire property. While partition sales are not the only outcome for heirs’ property, Thomas W. Mitchell, a lawyer and scholar at Texas A&M University argues that since 1900, judges have ordered them more frequently than alternative forms of partition.

Who Is Most Likely to Have Heirs’ Property

The extent of heirs’ property is not clearly understood. In a 2017 land use policy article, Gaither and Zarnoch wrote, “U.S. estimates concentrate almost singularly on approximations of heirs’ property prevalence among southern, rural, Black Belt African American landowners … these approximations range from thirty to roughly forty percent of all African-American owned land in the South. But … generational poverty in central Appalachia may be attributed, in part, to the proliferation of questionable land titles in that sub-region of the South.” The rural Appalachian population and the rural black population are the two populations in the Fifth District for whom heirs’ property is perceived as the most prevalent. Lack of access to, or distrust in, the legal system and services largely shapes which groups experience heirs’ property at high rates. (In other Federal Reserve Districts, the problem is most likely to occur among some Native American groups or in the colonias of southwest Texas.) For these populations, land loss has contributed to, and continues to exacerbate, wealth gaps in this nation.

Although there have been several studies over the decades, most of them are geographically small in scope; we don’t have a comprehensive understanding of how much U.S. land is heirs’ property. A 2019 article by Cassandra Gaither and Stanley Zarnoch referenced a 1978 study where five southern states asserted that 33 percent of black-owned land is heirs’ property. In addition, a 1984 report by the Emergency Land Fund (ELF) estimated that about 27 percent of black-owned parcels in 10 American Southeast counties were heirs’ property. Furthermore, the Atlanta Fed estimated that up to 11 percent of residential lots in its districts’ rural counties are heirs’ property.

Heirs’ property is notoriously challenging to track and quantify, as evidenced by the studies conducted thus far. Reports from the 1970s and 1980s are now dated; many cases of heirs’ property have been resolved since then — many to the adverse interest of families. In fact, when the ELF study was published, it reported that black agricultural land ownership had already fallen about 37 percent between 1910 and 1974, some of that loss attributable to heirs’ property. Beyond the recency of published reports, the data itself is hard to access, and parcels can be difficult to categorize as heirs’ property. Data that reports heirs’ property is incomplete, and only the laborious efforts of retrieving and parsing county-level records and connecting with landowners directly would reveal its true scope.

Heirs’ Property in the Fifth District

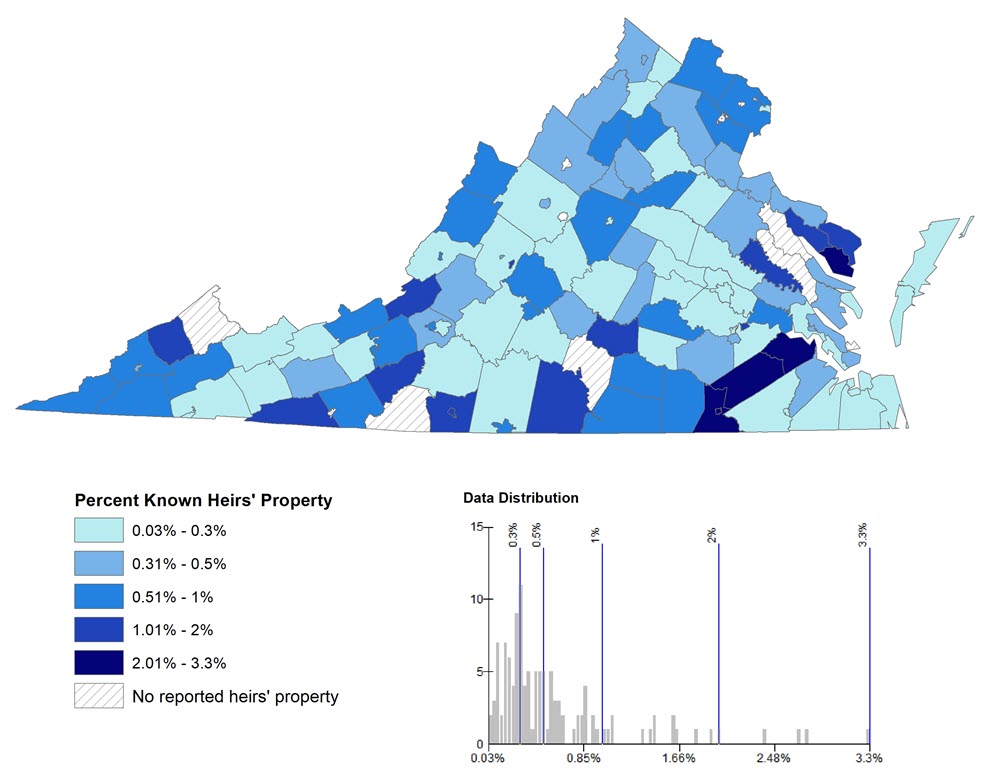

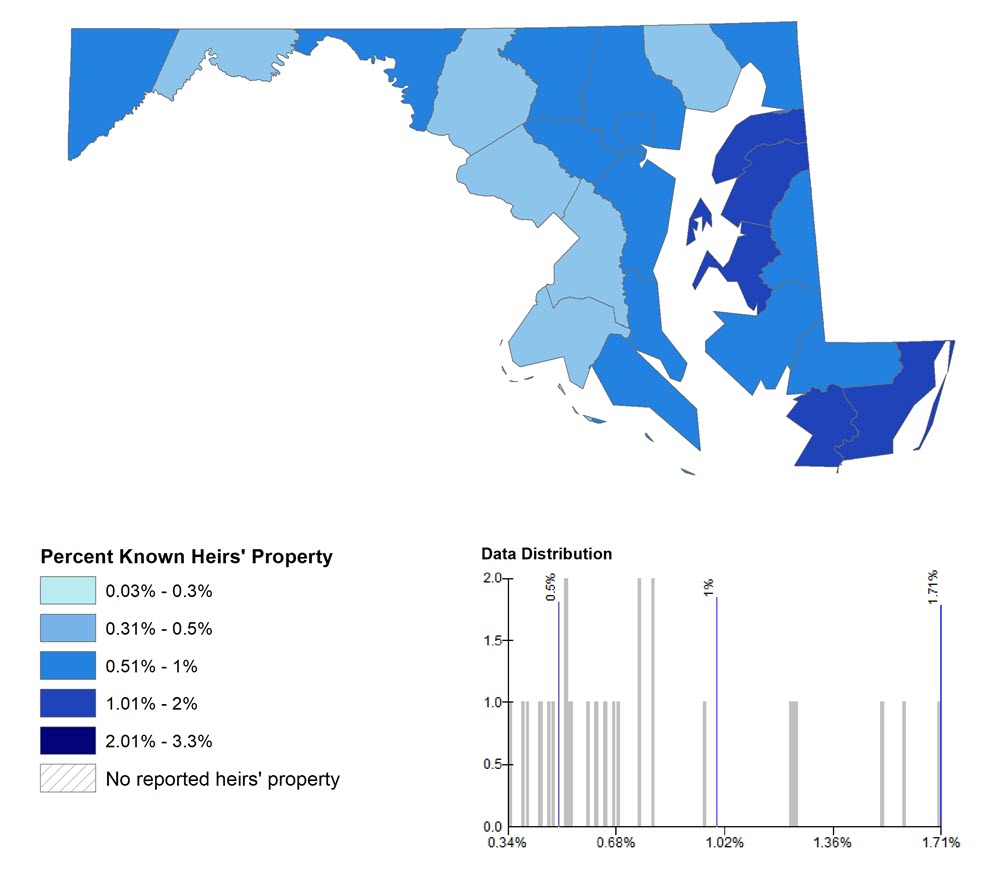

Although much of the discussion of heirs’ property prevalence is in the Black Belt south, engaging with nonprofit organizations in Virginia and Maryland led the Richmond Fed to start trying to understand the prevalence of heirs’ property in these two states. Similar to the Atlanta Fed’s approach, we used the 2012-2016 CoreLogic Real Estate Tax Dataset to establish which counties are likely to have high concentrations of heirs’ property, relative to each state. The maps below show the percent of county parcels that are known heirs’ property.

These maps represent a low estimate, or a floor, for the prevalence of heirs’ property. The data not only includes only residential properties (without farm or farmland), but also standards of record collection/reporting vary across counties, resulting in incomplete data representation of heirs’ property. In fact, many properties known to be heirs’ properties by our nonprofit partners did not show up in the data. Therefore, it is likely that the several counties labeled below as having no known heirs’ properties in the map actually do contain heirs’ properties, and the inability to capture that is a limitation of our data.

Nonetheless, this exercise provided areas of each state that likely have greater concentrations of heirs’ property. In Virginia, higher concentration areas include south central and southeastern counties (from Halifax County to Surry County). An earlier report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated a notable concentration of heirs’ property in a similar, but smaller, area.

Thanks to Parker Agelasto of the Capital Region Land Conservancy, Ebonie Alexander of the Black Family Land Trust, Ellen Shepard of the Virginia’s United Land Trusts, and Alex Marre of the Cleveland Fed for their help in this work.

Have a question or comment about this article? We'd love to hear from you!

Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Additional Resources

“The impact of heir property on black rural land tenure in the southeastern region of the United States.” Emergency Land Fund, 1984.

Pippin, Scott, Shana Jones, and Cassandra Johnson Gaither. “Identifying Potential Heirs Properties in the Southeastern United States: A New GIS Methodology Utilizing Mass Appraisal Data. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service and the Carl Vinson Institute of Government at the University of Georgia, September 2017.

Deaton, B. James. “Intestate Succession and Heir Property: Implications for Future Research on the Persistence of Poverty in Central Appalachia.” Journal of Economic Issues, December 2007, vol. XLI no. 4, pp. 927-942.

Gaither, Cassandra Johnson, Ann Carpenter, Tracy Lloyd McCurty, and Sara Toering. “Heirs’ Property and Land Fractionation: Fostering Stable Ownership to Prevent Land Loss and Abandonment.” U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southern Research Station e-General Technical Report SRS-244, September 2019.

Expansion of New Law in Southeast May Stave Off Black Land Loss.” Atlanta Fed. Gaither, Cassandra Johnson, and Stanley J. Zarnoch. “Unearthing ‘dead capital’: Heirs’ property prediction in two U.S. southern counties.” Land Use Policy, September 2017, vol. 67, pp. 367-377.

Graber, C. Scott. “Heirs Property: The Problems and Potential Solutions.” Clearinghouse Rev., September 1978, vol. 12, pp. 273–276.