Intersecting Costs: Housing and Transportation in the Rural Fifth District

Our recent issue of Econ Focus covered a number of challenges facing small towns and rural areas, including the need for affordable, quality housing for low- and middle-income households. Despite typically lower housing costs in rural areas compared to urban areas, nearly four out of 10 low- and middle-income households in the rural Fifth District are housing cost burdened, meaning they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing.

Yet, access to housing is only part of the bigger story of households’ access to jobs, services, and amenities. Transportation also looms large. Housing and transportation represent the two biggest expenses for households on average, and transportation costs tend to increase with rurality. This article builds on previous analysis by exploring combined housing and transportation expenses across rural areas in the Fifth District.

Housing and Transportation in Rural Communities

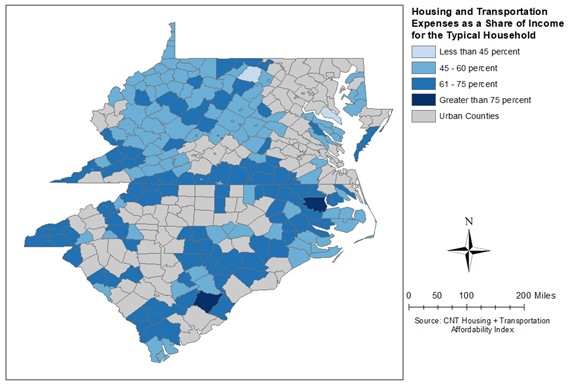

Compared to urban households throughout the Fifth District, rural households earning the area median income (which we’ll refer to as a “typical” household) tend to spend less on housing and roughly the same amount on transportation. However, as a share of household income, housing expenses in rural communities are on par with urban communities while transportation expenses are notably higher. According to the Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT), housing and transportation expenses, together, are considered affordable when they account for no more than 45 percent of household income. The typical urban and rural household both exceed that threshold, but the typical rural household exceeds it to a much greater degree, spending about 60 percent of their income on housing and transportation expenses.

Rural counties in which typical households spend a relatively large amount of their income on both housing and transportation expenses are located throughout the Fifth District. As of the latest update of CNT’s H + T Index in 2017, there are only two rural counties where the typical household spends less than 45 percent of their income on housing and transportation combined: Hampshire County, West Virginia, and St. Mary’s County, Maryland. The two counties where the typical household spends more than three quarters of their income on housing and transportation are Bertie County, North Carolina, and Williamsburg County, South Carolina.

Local Trade-offs Between Housing and Transportation

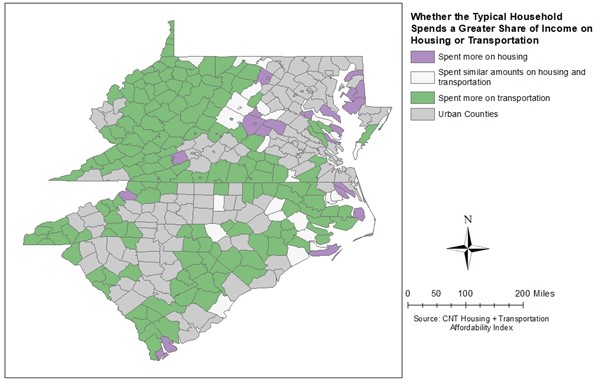

Transportation costs tend to increase as households move away from the city center for two primary reasons: Workers end up being farther away from their place of employment, or all common destinations are more diffuse in suburban and rural spaces. As a result, rural households travel about 33 percent more than urban households. As seen in the map below, typical households in most rural counties throughout the Fifth District spend a larger share of their income on transportation than on housing. This is also the case in urban areas in western parts of the Fifth District, but in urban parts of Maryland, Eastern Virginia, and the Eastern Carolinas, households tend to spend more on housing than on transportation.

Policy Solutions

Transportation policy solutions are often thought of in an urban context, and long travel times might seem unavoidable in low-density, rural communities. But just as in an urban setting, many rural transportation policy options are aimed at providing alternatives to private vehicle usage. Here we discuss three policy solutions:

1. Investing in public transportation

2. Investing in placemaking

3. Expanding broadband infrastructure

Investing in Public Transportation

While often considered a solution for more densely populated communities, there is relatively recent evidence of growing demand for public transit in rural areas. For example, one study conducted between 2007 and 2015 showed that rural public transit ridership increased by 8.6 percent per capita. The benefits to a rural public transportation system include increased resident accessibility to jobs, health services, educational opportunities, and other local amenities.

Access to public transportation is especially important for seniors, persons with disabilities, and households that do not have access to a personal vehicle. In the Fifth District, seniors make up a larger share of the population in rural areas compared to urban areas (19 percent versus 15 percent), as do persons with disabilities (17 percent versus 12 percent). About 7 percent of households do not have access to a vehicle across both urban and rural parts of the Fifth District.

The type of public transportation system depends on how the program will be funded, community density, and community preferences. On-demand travel may be most effective in some areas, while in others, fixed-route is feasible in more densely populated places. Country Roads Transit, which has served Randolph and Upshur counties in West Virginia since 2006, takes a hybrid approach by providing both fixed routes and special pickups and drop-offs upon request. In addition to revenue from rider fares, Country Roads Transit has been financially supported by grant funding and private and nonprofit contributions.

Investing in Placemaking

Most small towns were originally designed with pedestrians in mind. Engaging the community to update infrastructure and public spaces is not only a strategy for improving walkability and connecting local residents with amenities, but also improving streetscapes in small towns makes communities safer for pedestrians and drivers by encouraging reduced driving speeds. At the same time, locating new housing opportunities close to town centers reduces reliance on personal vehicles for everyday trips.

As discussed in our recent Econ Focus article, many small towns have underutilized properties close to their town center. In many cases, these properties have good bones and can be converted into housing or commercial space to revitalize the town center. For example, in Harrisonburg, Virginia, designer and entrepreneur Kristen Moore led the renovation of Big L Tire Pros, an unused tire shop and garage space built in the 1940s. Moore used federal and state historic tax credits to convert the building into an award-winning, mixed-use space that houses the Magpie Diner, Bakery at Magpie, Chestnut Ridge Coffee Roasters, and a coworking space called The Perch. This building renovation has enhanced foot traffic, has improved the success of nearby restaurants, and has been a catalyst for other adaptive reuse rehabilitations in the neighborhood.

Redeveloping streets to be pedestrian-oriented is especially beneficial in small towns that are bisected by highways, such as Hillsboro, Virginia. Recently, Hillsboro updated the stretch of State Route 9 that serves as the town’s main street. Upon entering Hillsboro, drivers are encouraged to slow down by roundabouts at either end of the town and narrowed lanes within the town. Parking lanes and raised sidewalks also protect pedestrians. According to Hillsboro Mayor Roger Vance, “There were people who had never walked through town, ever, because it was simply not safe to do. It’s created a different sense of a place where you can walk down a street.” As a result of the award-winning project, residents are more likely to walk than drive short distances within town and have a greater feeling of safety and community connectivity. In addition, residents have benefitted from water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure upgrades that were implemented simultaneously.

Expanding Broadband Infrastructure

Having access to broadband reduces the number of trips for rural households. For example, improved access to broadband would allow rural residents to visit their doctors over telehealth visits, reducing the need to drive to doctors’ offices or hospitals to receive medical care. Broadband would also further expand rural residents’ access to amenities and economic opportunities not available in their local communities, such as online education and remote work.

Federal legislation, such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, has prioritized expanding access to broadband nationwide, with a focus on rural areas. State and local governments can further create incentives for local utilities to extend fiber to rural communities. For example, Virginia passed legislation to permit utilities to recover costs associated with extending fiber-optic cable lines to rural communities. This supported Dominion Energy’s Rural Broadband Program, in which Dominion Energy will lay fiber-optic cable lines connecting urban to rural communities. They are partnering with local internet service providers to then connect rural households to the newly available fiber lines.

As an example of how local governments can facilitate the expansion of broadband to their residents, Hillsboro, Virginia, used their Route 9 streetscape improvements as an opportunity to lay the conduit for fiber to each residence along the street. The town then attracted an internet service provider using the American Rescue Plan Act funding to cover the initial cost of running fiber cable through the town and to each residence, and then providing a limited-time grant to the company to cover the initial installation cost for individual households to connect to the fiber network.

Conclusion

When we look at housing and transportation costs together, we see that compared to urban households, rural households throughout the Fifth District spend a larger share of their income on these two expenses. In most rural counties, households spend more on transportation than housing, pushing these combined expenses well beyond what is commonly considered affordable. Policymakers, local leaders, and community-based organizations can help defray rural residents’ transportation expenses by reducing the number of trips requiring a personal vehicle while at the same time improving local connectivity.