Housing the Workforce in the Rural Fifth District

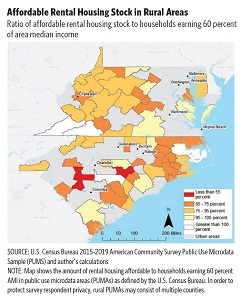

Although real estate is often less costly in rural areas than in urban areas, many low- and middle-income households in rural areas struggle with housing expense. There are multiple reasons why rural households end up financially constrained by housing costs. First, incomes tend to be lower in rural areas. Second, there are limited available units — multifamily or single family — in rural areas for reasons that reflect the unique challenges of the rural housing landscape.

Although these challenges to finding affordable, quality housing tend to cut across the rural Fifth District, there are also differences that arise from the diversity of rural areas. Rural communities possess unique assets that they can use to leverage policy and market-based tools to resolve housing shortages. Depending on local constraints, communities may choose to preserve or repurpose existing properties or create new units to make housing more affordable.

Typically, the terms "affordable housing" and "workforce housing" are used to refer to housing that is affordable to low- and middle-income households, respectively. This article uses the term "low- to middle-income housing" to refer to both — that is, all housing affordable to low- to middle-income households earning up to 120 percent of the area median income (AMI).

The Burden of Rural Housing Cost

When housing practitioners think about the affordability of housing expense, they consider households to be "cost burdened" if rent or ownership costs account for more than 30 percent of gross income. For example, for a household earning $48,000 per year, or $4,000 per month, a home that costs up to $1,200 per month would be considered affordable at that income level (because $1,200 is 30 percent of $4,000). If the household lives in a unit that costs more than $1,200 per month, they would be considered housing cost burdened. This includes households that willingly spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. Housing cost burden can be distinct from housing instability, which can include households facing eviction or experiencing homelessness.

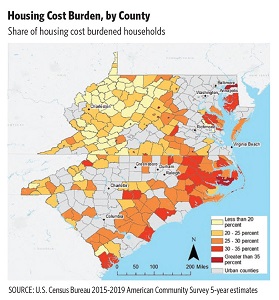

In the Fifth District, rural households are only slightly less likely to be housing cost burdened than urban households. Twenty-five percent of rural households at all income levels are housing cost burdened, versus 28 percent of urban households. Within rural parts of the Fifth District, the share of housing cost burdened households is greatest in areas along the coasts of Maryland and the Carolinas and is less pronounced in the Appalachian region. (See map below.)

"School Quality as a Tool for Attracting People to Rural Areas," Economic Brief No. 20-09, August 2020

Because all affordable home repair programs are subject to resource constraints, many of them limit eligibility to a subset of low- to middle-income households. For example, Section 504 serves homeowners earning 50 percent AMI or less and offers loans of up to $20,000 per home. Other programs prioritize households that include seniors, children, or persons with disabilities. As a result, not all low- to middle-income households will be eligible for these programs. Rebuilding Together Kent County, located on Maryland's rural Eastern Shore, is an example of a program that rehabilitates homes for low-income homeowners. After performing a home assessment, Rebuilding Together Kent County coordinates home repairs to improve the health and safety of the home and home modifications as needed for seniors and persons with disabilities to reduce the risk of falls or injury. In 2020, the organization served 21 unique households, all of whom had incomes below 80 percent AMI. The majority of households served reported improved physical and mental health as a result of the program, and 40 percent reported that their home increased in value.

Community Land Trusts

One mechanism for preserving low- to middle-income housing in the long term is community land trusts (CLTs), through which nonprofit, community-based organizations purchase and retain ownership of the land on which housing is built. Residents who purchase homes located on CLT land benefit from establishing equity, and resale formulas guarantee that the homes will continue to be affordable to low- to middle-income owners in the future (though this dampens appreciation). In many cases, CLTs continually support residents in ways that range from homebuyer education classes to ongoing financial and maintenance counseling, resulting in lower rates of mortgage delinquency and foreclosure.

For example, Piedmont Community Land Trust (PCLT) is a Fifth District CLT that serves Charlottesville, Va., and the surrounding rural counties. PCLT creates homeownership opportunities for households earning 80 percent AMI or less by purchasing land and holding it in trust while the homeowner purchases the home on the land. The homeowner and PCLT enter into a 90-year ground lease on the land, which renews automatically. Removing the cost of land from the purchase price reduces monthly payments for the homeowner by anywhere from 20 percent to 40 percent. PCLT works in partnership with a community development financial institution that administers down payment assistance to eligible homebuyers.

Although CLTs have been around since the 1960s, many communities lack knowledge about how they operate and, as a result, are hesitant to adopt policies to encourage their establishment. Even with the support of the local community, creating a new CLT can be challenging as it requires coalition building, financial resources, and organizational capacity. Acquiring land can be difficult or expensive, particularly in counties where land is priced at a premium. Lastly, CLTs are not a suitable mechanism for resolving all low- to middle-income housing shortages because they often limit eligibility to a subset of low- to middle-income households, such as households with incomes below 80 percent AMI.

Repurposing Existing Properties

Underutilized or vacant properties in rural areas provide an opportunity to create low- to middle-income housing and simultaneously prevent or resolve blight.

Many small towns have vacant commercial or industrial properties that could be rehabilitated by a developer. Finding a developer willing to undertake property acquisition and redevelopment costs might be difficult for some rural jurisdictions, and in some cases current owners might be unwilling to sell their properties. Local governments and community-based organizations can facilitate this process by brokering relationships between property owners and developers and minimizing permitting and redevelopment costs for viable adaptive reuse projects.

Graham, N.C., is home to an example of an industrial property that was redeveloped into affordable housing in 2017. Prior to the building's redevelopment, the Oneida Mill Lofts had lived a previous life as a textile mill before sitting vacant for two decades. Today, the property consists of 133 one- and two-bedroom units affordable to households earning up to 60 percent AMI. The development team took care to preserve the historic character of the building during redevelopment.

Communities with a significant network of vacant and abandoned properties might benefit from establishing a land bank, which is an entity that systematically acquires properties and prepares them for sale or lease. In addition to converting previously unused property to low- to middle-income housing, land banks are a strategy for improving public safety, increasing property values of adjacent properties, and expanding the jurisdiction's tax base. Within the Fifth District, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland have legislation enabling land banks. CLTs may complement land banks if the land bank agrees to sell remediated land to the CLT to redevelop.

Acquiring vacant and underutilized properties can be challenging. For a land bank to assume control of a vacant property, either the owner has to willingly transfer the property or the property needs to be foreclosed upon, usually due to a tax foreclosure. After either of these events occur, the land bank may need to overcome a number of legal obstacles to assume ownership of the property, such as issues related to property right law, tax foreclosure law, or titling defects. After obtaining new land, the land bank may need to finance remediation activities and may experience funding limitations.

Roanoke, Va., established a land bank in 2019 with the goal of converting abandoned and derelict properties into affordable housing. After properties have gone through the tax delinquency process, the city will turn them over to a partner organization, Total Action for Progress (TAP). TAP will then work with other nonprofits, such as Habitat for Humanity, to renovate or construct new affordable housing on the site.

Direct Subsidies

Several public programs exist to provide direct rental subsidies to low-income households. Housing choice vouchers (HCVs) and USDA-RD Section 521 (which subsidizes rent in some USDA-RD Section 515 properties) are two types of direct rental subsidies in rural spaces. In addition to these, local nonprofit and public entities can create public-private partnerships with local employers to develop dedicated housing affordable to low- to middle-income households, as has been done in urban communities with constrained rental housing markets.

HCVs and USDA-RD Section 521 do not reach all income-eligible households due to funding limitations. Due to limited availability, the median waitlist length for HCVs is one and a half years nationally and up to seven years in high-need areas. Only households earning 50 percent AMI or less are eligible for HCVs. By definition, USDA-RD Section 521 serves only Section 514, 515, or 516 properties, which meet the needs of only a fraction of low- to middle-income households.

Public and nonprofit organizations can help working families afford housing by creating programs to help cover the upfront costs associated with purchasing a home. For many low- to middle-income households, these costs are a greater barrier than monthly mortgage payments. Down payment assistance (DPA) and closing cost assistance programs can provide either grants or low-interest loans and are usually intended to help low- to middle-income first-time homebuyers. In the Fifth District, state-level organizations in North Carolina and South Carolina offer DPA programs for qualifying households, whereas other local jurisdictions use these programs to allow public employees to live locally. Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia go a step further to provide funding to help with closing costs. These state-level organizations also provide low-cost mortgages to qualifying households.

Conclusion

As evidenced by the persistence of housing cost burdens and measured housing shortages, rural areas have unmet low- to middle-income housing needs. Local housing market conditions, including demographics, housing stock quality, and other assets, vary and therefore point toward different policy solutions. At the same time, many available policy solutions are designed for low-income households but not middle-income ones. This reflects what the Richmond Fed has been hearing from businesses in rural areas: that local housing shortages have made it challenging to attract and retain workers, especially low- to middle-income workers.

In addition to longstanding housing challenges in rural communities, the pandemic-driven migration of households from more densely populated areas has increased demand for housing in rural markets, reducing the amount of time homes spend on the market and putting upward pressure on prices. Rural areas that have lost population in recent years may welcome additional residents as contributors to their tax base and community. At the same time, this recent trend heightens the need for new low- to middle-income housing solutions in rural communities throughout the Fifth District.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.