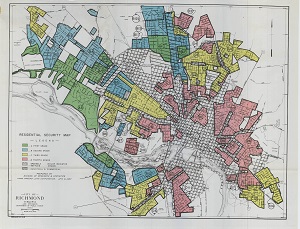

The HOLC grades were used to construct color-coded city maps in which the lowest graded sections were shaded red — thus giving birth to the term "redlining." Maps based on similar methods and biases were drawn at about the same time by the Federal Housing Administration, an institution that would play a major role in post-World War II mortgage markets. It is difficult to judge the extent to which these early redlined maps exerted an independent influence versus how much they simply reflected preexisting practices in real estate and lending markets that may have continued regardless of the maps. What is certain is that the maps represented the official codification of practices that made it difficult for minority and lower-income families to obtain mortgages for home purchases or improvements in redlined neighborhoods. Shut off from homeownership, many families were blocked from what was arguably 20th century America's most important avenue for the intergenerational accumulation of wealth.

A Response to Redlining

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was enacted in 1977 as part of an attempt to remedy the legacy of redlining and to encourage banks to meet the needs of minority and low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities. Although it was meant to address long-standing issues, it was enacted during a period of heightened concern about declining conditions in the nation's urban neighborhoods.

While the CRA did not explicitly target racial discrimination, it was meant to complement civil rights laws that had been passed during the previous decade to address inequities in housing and lending markets. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed many of the discriminatory practices that had shaped the U.S. housing market, including racially restrictive covenants and zoning laws. (Although the U.S. Supreme Court had barred states from enforcing racially restrictive covenants in its 1948 decision in Shelley v. Kraemer, the decision had not barred their use by private parties.) The 1968 law's prohibition of discriminatory mortgage lending was buttressed by the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, which prohibited financial institutions from discriminating against credit applicants based on, among other protected characteristics, their race, color, religion, national origin, or sex. The Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) of 1975 assisted the enforcement of antidiscrimination laws. It required banks to collect and disclose data about the ethnicity and race of credit applicants to aid in the identification of discriminatory lending practices.

Data collected under HMDA played a role in informing congressional debate over the CRA. Sen. William Proxmire (D.-Wis.), the CRA's main architect, stated on the Senate floor, "The data provided by [the HMDA] remove any doubt that redlining indeed exists, that many credit-worthy areas are denied loans. This denial of credit, while it is certainly not the sole cause of our urban problems, undoubtedly aggravates urban decline."

The CRA declares that "banks have a continuing and affirmative obligation to help meet the credit needs of their local communities, including low- and moderate-income (LMI) neighborhoods where they are chartered, consistent with the safe and sound operations of the institutions." The Act directed bank supervisory agencies to examine banks periodically to assess their records of meeting the credit needs of their entire communities, including LMI neighborhoods. To give the CRA teeth, regulators were to factor in their CRA assessments when deciding whether to approve a bank's applications for mergers, acquisitions, or branch openings.

The CRA has undergone several legislative changes. Changes enacted in 1989, for instance, required bank supervisors to publicly disclose institutions' CRA ratings and performance assessments. In addition to legislative changes, bank supervisors have periodically reviewed and revised the regulatory framework they employ to implement the CRA. Regulatory changes in 1995, for example, increased the importance of objective performance measures relative to the more subjective and process-oriented criteria that supervisors had previously emphasized.

Bank Supervision Under the CRA

CRA exams are conducted at roughly three-year intervals by a bank's federal supervisor — either the Fed, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), or the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Banks of different sizes are subject to different CRA tests. Large banks — those with assets above $1.384 billion — are evaluated under separate lending, investment, and service tests. Small banks — those with assets of less than $346 million — are primarily evaluated under a retail lending test. A blended set of tests is applied to banks in between.

For each test, banks are evaluated based on their performance within their geographic "assessment areas," which, as a practical matter, define the communities that they are obligated to serve under their charters. As part of a CRA exam, banks propose assessment areas, which bank supervisors then evaluate. The CRA spells out rules for the delineation of assessment areas, which "may not reflect illegal discrimination" and "may not arbitrarily exclude low- or moderate-income geographies." A bank's assessment areas typically consist of already-defined areas such as metropolitan statistical areas or cities or counties in which the bank locates its main office, branches, and deposit-taking ATMs. Assessment areas are frequently expanded to include contiguous geographies where a bank makes a substantial amount of its loans.

According to William Nurney, a senior manager in the Richmond Fed's Supervision, Regulation and Credit department, which conducts CRA assessments for the Richmond Fed, "We go through an analytical process, before every exam, where we look at the assessment areas that the bank has given us. We apply the criteria from the existing CRA regulations to determine, 'Does that assessment area make sense within the context of the reg or does it not?'" In cases where proposed assessment areas do not appear to conform to regulation, Nurney adds, "We'll ask them, 'Why did you draw the boundary here instead of there?' We really try to understand where they're coming from." The back-and-forth process usually produces an agreed-upon area, he says.

When conducting the CRA lending tests, bank examiners address three questions about a bank's record. First, is the bank meeting the needs of its community at large by lending sufficiently within its assessment areas? Here, examiners gauge whether a bank's overall lending is sufficient relative to its deposit base and whether the bank's lending inside its assessment areas is sufficient relative to its lending outside the areas. Second, is the bank making a sufficiently high fraction of its loans to borrowers located in LMI census tracts? Finally, is the bank making a sufficiently high fraction of its loans to LMI borrowers?

The CRA's investment test evaluates a bank's record of serving its assessment areas through qualified community development investments. "For a large bank's investment test, we basically look at the bank's securities portfolio to see how much of it consists of qualified CRA investments," says Nurney. "Those would include investments that focus on affordable housing, such as bonds issued by the Virginia Housing Development Authority. Another qualified investment would be a bond issued by a qualified small business development company."

The CRA's service test evaluates the availability and effectiveness of a bank's retail banking services and the extent of its community development services. "We look at where a bank has opened and closed offices to assess whether the changes have positively or negatively affected their ability to service their assessment area as a whole," Nurney explains. "We also look at a bank's service activities, such as whether the bank's officers serve on the boards of community development organizations — Habitat for Humanity is one example that comes to mind."

There are four possible CRA ratings: Outstanding, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve, and Substantial Noncompliance. According to a 2020 report by the Congressional Research Service, approximately 97 percent or more of the banks examined between 2006 and 2018 received CRA ratings of Satisfactory or Outstanding.

CRA Rationales and Criticisms

For proponents of the CRA, the law was needed to overcome market failures that may have inhibited lending in low-income neighborhoods, even in the absence of discrimination. By its nature, lending is about risk assessment, which requires information that is often in short supply in lower-income markets. Compared to higher-income neighborhoods, lower-income neighborhoods often have fewer home sales and more varied housing structures, which makes property appraisals challenging. In addition, credit evaluations can be more costly for lower-income borrowers, who often have short or irregular credit histories. According to former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, "The high costs of gathering information, together with the difficulty of keeping information proprietary, may have created a 'first-mover' problem, in which each financial institution has an incentive to let one of its competitors be the first to enter an underserved market."

In the eyes of many, the CRA serves as a coordinating mechanism to increase the number of transactions in low-income lending markets, thereby increasing the availability of information and helping to overcome the informational "first-mover" problem. The CRA may also help overcome another "first-mover" problem: peoples' reluctance to be the first to invest in housing improvements in a poor neighborhood.

Critics of the CRA contend that credit markets tend to be highly efficient — that, if there were profits to be made from lending to LMI communities, banks would readily make loans without regulatory intervention. This proposition is particularly true today, they argue, because institutional changes that have occurred since the law's 1977 enactment have made financial markets increasingly competitive. According to Diego Zuluaga, writing in a 2019 essay published by the Cato Institute, "Branching liberalization and the advent of online lending have allowed for freer local bank entry, substantially reducing the likelihood of persistently low lending rates in LMI communities." He argued that the emergence of nonbank lending has had a similar effect, pointing to data from the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection showing that the largest U.S. nonbanks, which are not subject to CRA regulation, actually made a higher percentage of their mortgage loans to LMI borrowers in 2017 than the largest U.S. banks, which are subject to it.

CRA critics also contend that the law is costly to administer, encourages banks to make risky loans, and undermines their ability to diversify their loan portfolios geographically. In addition, some observers have argued that the current CRA framework perversely discourages banks from adding new branches or entering new lending markets in cases where the banks perceive that these activities may cause an expansion of their CRA-related requirements.

Whatever the CRA's shortcomings, numerous studies have found evidence suggesting that it has at least partially achieved the core goal of increasing banks' LMI lending. One such study, by Robert Avery of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Glenn Canner of the Federal Reserve Board, and Raphael Bostic, now president of the Atlanta Fed, examined survey data collected by the Board about the performance and profitability of CRA-related lending. The study found that the "majority of surveyed institutions engaged in some lending that they would not have done in the absence of the act." They also found that "the vast majority of institutions ... were able to do so profitably," but "that a significant minority incurred losses from some of their marginal CRA-related lending." The researchers concluded with the caveat, however, that the CRA's effect on loan volumes and profitability appeared to be small. (Bostic was a professor at the University of Southern California at the time of this research.)

Reform Proposals

In October 2020, the Fed published an advance notice of proposed rulemaking to seek public input about the modernization of its CRA regulatory and supervisory framework. The notice advanced several reform proposals and posed numerous questions with the goal of eliciting responses from community groups, financial industry representatives, and scholars.

A key question was how to best define bank assessment areas so that they do not reflect illegal discrimination or arbitrarily exclude LMI census tracts. Some community advocates favor a broadening of assessment areas. "This is a huge area," says Josh Silver of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC). "We think it's critically important to expand assessment areas to places where banks do a significant amount of lending beyond their branches." The NCRC also favors incorporating race and ethnicity more explicitly in the determination of CRA assessment areas, proposing that CRA exams "require banks to affirmatively include communities of color in their assessment areas." While usually stopping short of favoring an outright expansion of assessment areas, some bankers have advocated flexibility that would allow bank examiners to give them credit for community development activities outside their current assessment borders.

The Fed is considering a variety of approaches to assessment areas. For large traditional banks, it has proposed expanding assessment areas to better reflect activities, such as deposit taking and loan origination, that take place in geographies far outside of their currently delineated assessment areas. Such an approach is being considered for banks with high concentrations of online business. For pure online lenders without physical loan-making locations, the Fed has proposed the establishment of national assessment areas in lieu of the current approach, which bases assessment areas on the locations of an online bank's main office.

The Fed also asked for comments about changing the CRA ratings system. "The CRA has done some tremendous good, but the full potential is not realized," says Silver. "Part of the issue is CRA ratings. About 98 percent of banks pass, and 90 percent get Satisfactory, which is like a B. Imagine if 90 percent of the students in the class are getting a B — it wouldn't exactly encourage excellence." Silver and others have proposed adding different gradations or adopting numerical scores that would similarly differentiate banks' CRA exam outcomes. Some bankers also appear to favor a rating system that would better differentiate them from their peers. To make the ratings more consequential, the NCRC also favors strengthening the role of ratings in bank merger reviews.

The Fed proposal seeks to increase the transparency of CRA lending tests. One idea is to set quantitative targets based on community and market standards. In the case of, say, mortgage lending, the percentage of a bank's mortgages in an assessment area that are made to LMI families would be compared to a community benchmark based on the percentage of households in the area that are LMI and to a market benchmark based on the percentage of peer-bank mortgages in the area that are LMI. One idea is to set quantitative targets based on community and market standards. In the case of, say, mortgage lending, the percentage of a bank's mortgages in an assessment area that are made to LMI families would be compared to a community benchmark based on the percentage of households in the area that are LMI and to a market benchmark based on the percentage of peer-bank mortgages in the area that are LMI.

As a general matter, the banking industry is receptive to the idea of increased transparency. "One of the complaints we hear from banks is that there isn't a lot of predictability about what kind of activities and products are viewed favorably — particularly community development activities," says Paige Paridon of the Bank Policy Institute, which conducts research and advocates for the banking industry. Thus, banks have asked for greater clarity about what level of activity is required to achieve certain ratings.

The banking industry is also asking for greater flexibility. "There's a need for the CRA and the regulators to adapt some of the assessments and performance tests under the CRA to recognize that there are just such a broad range of business models," says Paridon. "We would like to see increased flexibility about looking at the different ways banks serve their communities."

Yet transparency and flexibility may be hard to combine. "It's a difficult trade-off," says Paridon. "We recognize that it's hard for regulators to offer the transparency that comes with quantitative standards while also maintaining flexibility."

Next Steps

There is one outstanding issue, in the view of bankers and consumer advocates, that cannot be addressed by the supervisory agencies alone — and that is the fact that banks are subject to CRA regulation, and nonbank lenders are not. The banking industry favors expanding the CRA's jurisdiction to nonbank lenders to create a more level playing field for compliance. "To the extent that you are providing the same sort of products and services as banks, you should be held to the same requirements," says Paridon. On this, consumer advocates tend to agree with the bankers. "If you have CRA applied to some financial industry sectors and not others, you will not be as effective in reaching traditionally underserved or formerly redlined communities," says Silver. "The community reinvestment obligation should apply throughout the financial industry." Such an extension of the CRA's scope, however, would require new congressional legislation.

Thus, regulatory reform remains the main task at hand. The Fed, OCC, and FDIC are currently working toward creating a CRA framework that is consistent across the agencies. "There have been a lot of conversations and discussions — a real effort to find an approach that all three agencies can sign off on and implement and reinforce," says Nurney of the Richmond Fed. "They have been at it since last year, and they have received a lot of insights based on industry and public feedback." A likely next step is for the agencies to formulate a set of proposed rules that can be published for public comment.

READINGS

Avery, Robert B., Raphael W. Bostic, and Glenn B. Canner. "Assessing the Necessity and Efficiency of the Community Reinvestment Act." Housing Policy Debate, 2005, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 143-172.

Barr, Michael S. "Credit Where It Counts: The Community Reinvestment Act and Its Critics." New York University Law Review, May 2005, vol. 80, no. 2, pp 513-652.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. "Community Reinvestment Act: Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking; Request for Comment." Federal Register, Oct. 19, 2020, vol. 85, no. 202, pp. 66410-66463.