Hurricane Helene's Impact on Housing in Western North Carolina

Approximately six months ago, Hurricane Helene brought devastation to parts of the Fifth District, with communities in Western North Carolina1 (WNC) sustaining particularly severe damage. Today, communities are still recovering from Helene's impact — from profound loss of life to loss of property and critical infrastructure.

Hurricanes can create unfavorable housing market conditions in affected areas, including damage to existing housing stock, reduction in housing supply, and deterioration of asset values. Prior to the storm, many WNC communities already exhibited signs of substantial housing market tightness. Now, Helene's destruction of residential real estate has disrupted the housing market, raising questions about the storm's long-term impact on housing availability and affordability.

A Tight Housing Market Before Hurricane Helene

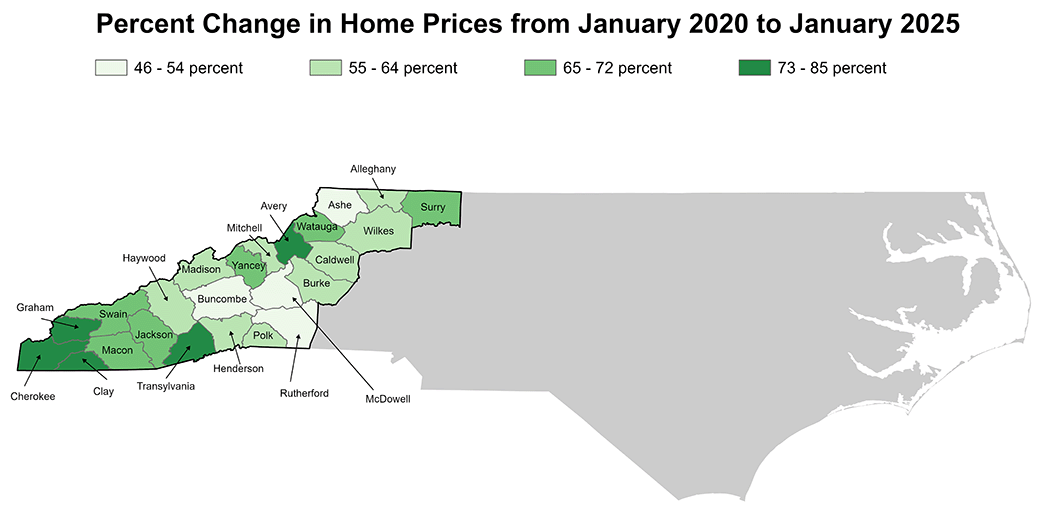

Prior to Hurricane Helene, housing availability and affordability were major concerns for many residents in WNC. Housing supply and demand imbalances driven partly by robust in-migration over the last decade have created housing affordability issues in the region. Many WNC communities have become hotspots for tourists, new residents, and retirees due to their picturesque landscapes and lower cost of living. Subsequently, home prices have surged over the last five years, outpacing state and national annual growth in most WNC counties during 2022.2 Home price growth has moderated over the last two years, but it still remains above national and state trends in many WNC counties.

Avery, Transylvania, Graham, Cherokee, Clay, Watauga, and Macon counties led the region with over 70 percent home price growth between January 2020 to January 2025, with most of that growth occurring during 2022. Even for some counties with less cumulative growth, such as Buncombe County (53 percent), home prices grew faster than the national pace (46 percent).

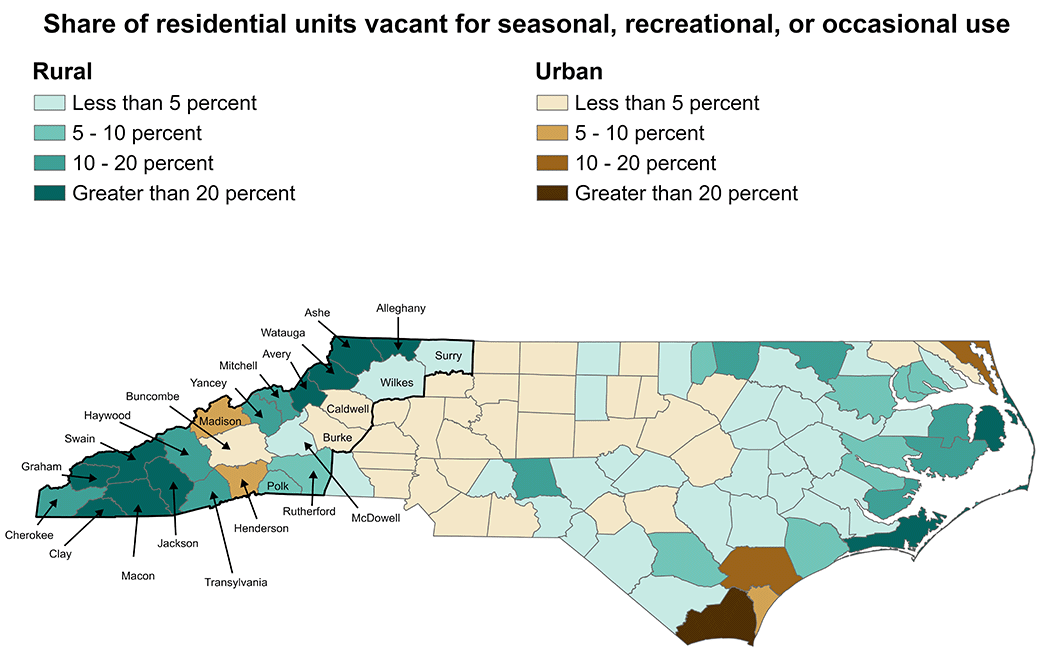

The outsized presence of leisure and hospitality in the region may also give rise to unique housing cost pressures. Vacation homes and short-term rentals are more prevalent in WNC than in other Fifth District counties, which could inadvertently reduce the supply of housing for full-time residents and place upward pressure on rents and home prices. The map below shows that many WNC counties, especially in the high-country region, have a higher share of residential units that are vacant for seasonal, recreational, or occasional use compared to other North Carolina counties.

Residential Real Estate Devastated by Helene

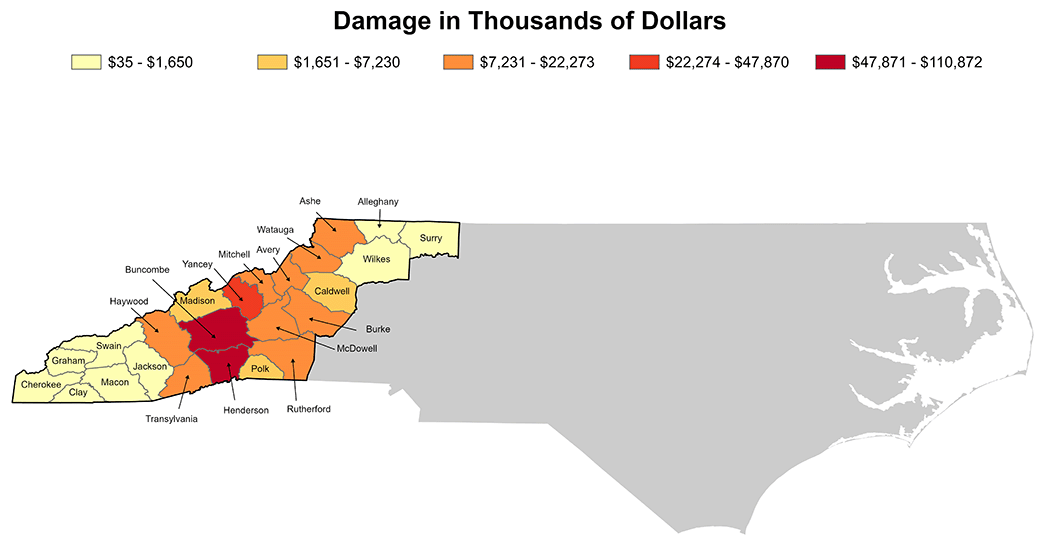

What has been most apparent in the aftermath of the storm is the visible structural damage incurred by thousands of residences in WNC. Underlying the physical damage to homes is the cost of temporary housing, rental and mortgage payments while being displaced, and personal property damage. In preliminary estimates from the North Carolina Office of State Budget, residential repair needs due to Hurricane Helene amount to over $12 billion. In addition to the cost of repairing physical damage to residential structures, an additional $3 billion is estimated to be needed for other housing assistance such as transitional housing for displaced individuals, personal property replacement, and disaster mitigation investments.

The extent of the damage and needs for assistance vary widely by geography. The Federal Emergency Management Agency's Individual Assistance dataset shows the total assessed housing damage for counties impacted by Hurricane Helene. To provide a rough estimate of the variation in the amount of damage incurred by homes in the WNC region, we calculate the total assessed damage for both homeowners and renters. However, it's important to emphasize that these figures do not represent the total damage incurred in these areas — only what has been reported as assessed. The maps below show the assessed damage as well as a per-unit measure using the number of housing units in each county.

In total, all 24 WNC counties had a combined assessed damage of $347 million, with Buncombe, Henderson, and Yancey counties having the highest reported damages.

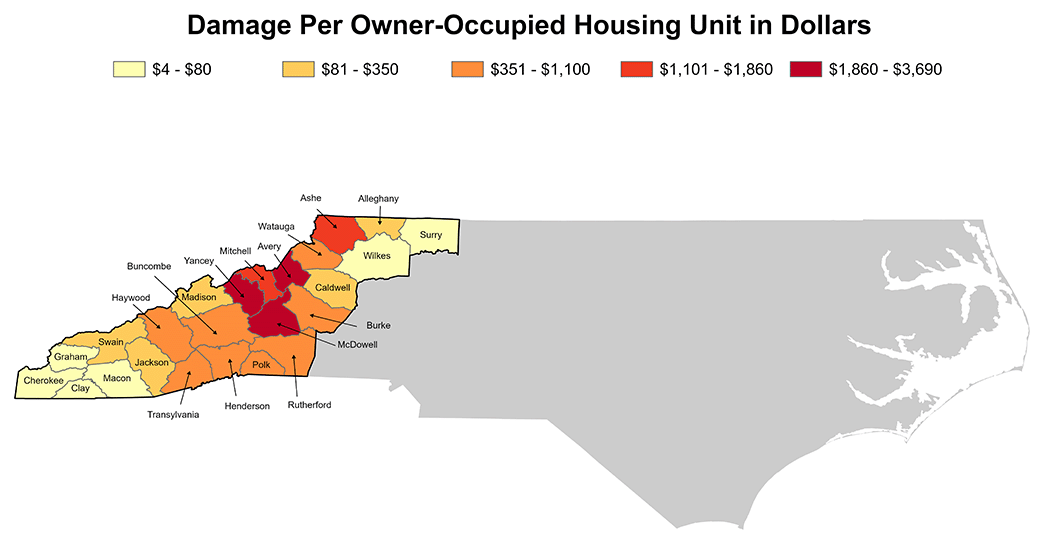

When looking at per-unit damage, the narrative changes slightly. McDowell, Avery, and Ashe counties, which are less populated, join Yancey County in having the highest damage per owner-occupied housing unit. This underscores that the damage borne per household is likely more extensive in these counties.3 The areas with the most severe damage may not be fully captured by county-level boundaries, however. At a more granular level, communities near bodies of water, such as the Swannanoa River and Lake Lure, sustained intense flood damage.

How Might the Storm Impact Housing Moving Forward?

Empirical evidence on the medium- and longer-term impact of hurricanes on housing markets is mixed. The severity of a storm and the social and economic characteristics of an area can create vastly different scenarios in the housing landscape. In one scenario, tight housing market conditions can worsen after a storm's impact, first due to a decline in housing stock and an increase in demand for housing as affected residents escape uninhabitable conditions. This scenario of restricted supply may be more acute in some of WNC's rural areas, where mountainous terrain may delay rebuilding efforts and increase costs. Additionally, efforts to increase housing supply may be delayed as resources are diverted to repair efforts. On the other hand, the impact of the storm may alleviate some housing market tightness as property values decline due to damage and residents temporarily relocate, reducing the demand for housing.

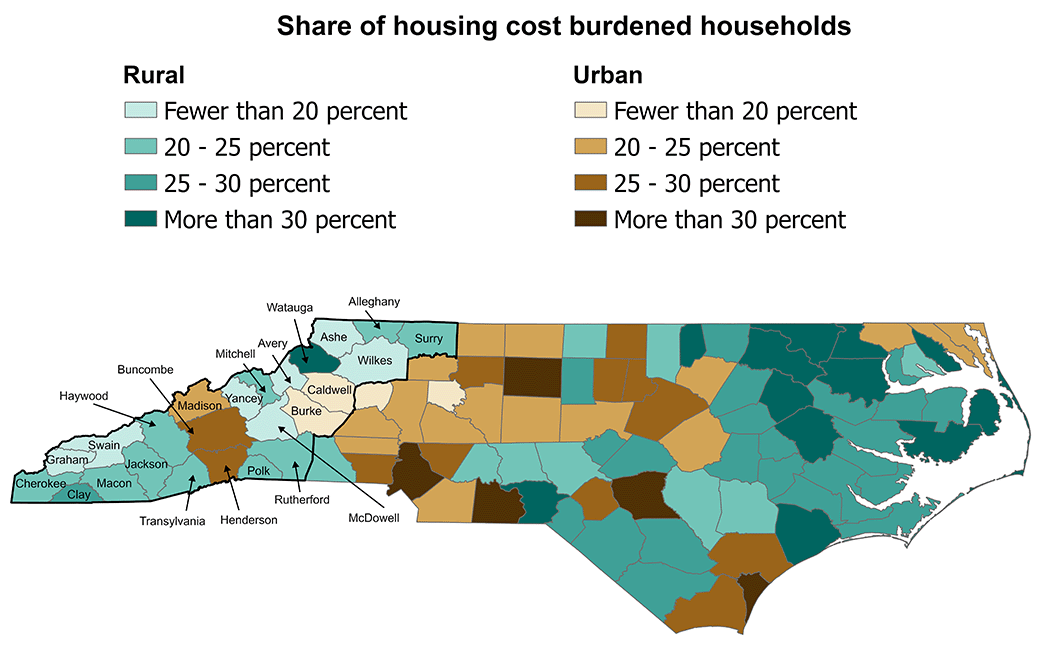

Renters face unique challenges after a hurricane, as the rental market responds to reduced housing supply and renters may face evictions due to unemployment or underemployment. This is likely a more acute issue for impacted urban counties, namely, Buncombe, Henderson, and Madison, where there is a higher share of renters. Residents of these counties also have a higher share of individuals who are housing cost burdened compared to surrounding rural areas, meaning they are more likely to spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. According to recent Zillow rent data, in the six months following Hurricane Helene, rent growth in Asheville softened by a few percentage points, going from 4 percent year-over-year growth in October 2024 to 2 percent in January 2025. This moderation may indicate an outflow of displaced residents that has reduced the demand for housing, especially since renters are more mobile. However, the longer-term impact on rent affordability is unknown and will depend on the return of displaced residents and the restoration of damaged rental units.

Closing Thoughts

The longer-term implications of Hurricane Helene on the housing landscape have yet to be realized. However, housing market disruptions due to damaged housing stock are already being felt. The response to the fallout will be key in sustaining and improving residents' ability to live in and return to the area in the months and years to come. Some initiatives are already underway to address current housing needs and mitigate the storm's longer-term impact on housing. For example, North Carolina has proposed three programs in its action plan for grant funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: rebuilding and repair of severely damaged homes, the construction of homes for low- and — moderate-income residents, and repair of rental housing stock. As rebuilding efforts continue, we are committed to relaying additional insights on the storm's lasting impact on our Fifth District communities.

Western North Carolina comprises Alleghany, Ashe, Avery, Buncombe, Burke, Caldwell, Cherokee, Clay, Graham, Haywood, Henderson, Jackson, Macon, Madison, McDowell, Mitchell, Polk, Rutherford, Surry, Swain, Transylvania, Watauga, Wilkes, and Yancey counties.

These are Alleghany, Avery, Burke, Caldwell, Cherokee, Clay, Graham, Haywood, Jackson, Macon, Madison, Mitchell, Polk, Surry, Swain, Transylvania, Watauga, and Yancey counties.

Per capita damage ranges are anywhere from $4 per housing unit in Clay County to almost $4,000 per housing unit in Yancey County.

Views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.