The High Point Initiative

Can giving drug dealers a second chance actually reduce crime?

Charles Myres started dealing drugs when he was 11 years old. He was arrested for the first time when he was 15 and was in and out of court for the next four years. In many cities, he would be a statistic today, one of the nearly 800,000 black men who are currently in prison or jail. But instead, Myres — a tall, slim 23-year-old who wears his hair in neat braids — has started a landscaping business with his brother and is raising three children with his girlfriend.

Myres happened to be a drug dealer in High Point, N.C., a city of about 100,000 people between Greensboro and Winston-Salem. In 2004, fed up with decades of high crime and drug violence, the police embarked on a new strategy to combat the city's open-air drug markets: Instead of locking up all the dealers, they would offer some a second chance.

The plan worked. Violent crime decreased dramatically and the drug markets remain closed. Inspired by the success, in 2008 the Department of Justice (DOJ) began a drug market intervention program that provided grants and training to implement the High Point model in more than 30 cities nationwide, including six in the Fifth District. As the country debates the best way to combat drugs and drug violence, the High Point initiative offers an alternative to the traditional model of arrest and imprisonment.

The High Point Model

The traditional model wasn't working in High Point, where open-air drug markets — dealers standing on corners and in parking lots to sell drugs to people who drove up in cars — had developed in several neighborhoods throughout the city. "We made dozens of arrests every month," says Marty Sumner, chief of the High Point Police Department (HPPD). Sumner was assistant chief when the drug market initiative began. "And as soon as we arrested someone, there were five more people to take his place."

Crack cocaine arrived in High Point in the 1980s, as it did in many other areas of the country. In neighborhoods that used to house workers for the region's textile and furniture mills, vacant homes became hideouts for dealers and addicts. Businesses moved away, the dealers became more brazen, and over time, the remaining residents became resigned to the conditions. "You had total disinvestment in the community," Sumner says. "Nobody cared and nobody called, because they saw it every day. They'd given up hope that we could change anything."

In the mid-1990s, the HPPD had worked with David Kennedy, then a researcher at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, on a program to reduce gun violence. Kennedy is currently the director of the Center for Crime Prevention and Control at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The program had been successful, but in 2003 there was a noticeable rise in violent crime; the number of murders, rapes, robberies, and assaults increased more than 10 percent over the year before, from 784 to 867. At that point, the city had the second-highest per capita violent crime rate in the state. Chief Jim Fealy believed that the open-air drug markets were the primary source of the violence and decided to ask Kennedy for help shutting them down.

Kennedy was the architect of a new method of policing called "focused deterrence," which involves carefully targeting a select group of chronic offenders in a crime hot spot.

The basic model is that police, prosecutors, and the community work closely together to identify the offenders who are the source of the problem. Then, the police inform the offenders at a group meeting that law enforcement is aware of their activities and watching them closely. If the dealers change their behavior, they won't be arrested, but if they continue, they will be prosecuted harshly. Community leaders are present at these meetings to inform the offenders that their behavior will no longer be tolerated by their families and neighbors and to offer social services. Kennedy describes three basic messages: "First, your own community needs this to stop. They care about you but they hate what's going on and it has to stop. Second, we would like to help you. And third, this is not a negotiation. We're not asking."

The first application was in 1995 in Boston, where there was a very high youth homicide rate. Police realized that the violence was a gang problem, and that although a small number of gang members actually did the killing, all the members committed lots of other crimes. So the police informed the gang members that "the price to the group for a killing will be attention to every crime that everybody in the group is committing. Using drugs, selling drugs, violating probation, driving unregistered cars, everything," Kennedy says. "It turned out that when all the groups were put on prior notice, the killing dropped off really quickly and dramatically." Operation Ceasefire reduced gun violence by 68 percent within a single year, according to the National Institute of Justice, the research branch of the DOJ.

A New Day in High Point

The key to implementing the model in High Point was to decide that the problem was not drugs per se but rather how they were being sold. Open-air drug markets breed "complete chaos in the public space," Sumner says. Buyers come from out of town, prostitutes know they can find both drugs and clients, and dealers battle each other for turf and customers. "It used to look like a McDonald's drive-through here. You couldn't even turn on to the street because of all the cars lined up to buy drugs," says Lt. Anthro Gamble, who was a narcotics officer at the time. If the city could shut down the markets — even if they didn't get rid of drugs completely — they could reduce the violence and create stability in the affected neighborhoods.

After analyzing the city's crime data, the police decided to target the West End neighborhood first. They held a series of public meetings to explain the initiative to the community and ask for their support, and then the narcotics agents went to work. They spent months observing the drug market to identify the dealers, and built cases against them using informants and undercover drug purchases.

One surprise was that the problem was limited to a relatively small number of dealers. "I figured there would be over 100 people that were really involved in the drug dealing. It seemed like they were everywhere," says Jim Summey, a former minister in the West End and the executive director of the High Point Community Against Violence (HPCAV), a nonprofit organization that works closely with the police department. But when police analyzed the data, there were actually only 16 active street dealers in that market.

Of those 16, four were arrested right away because police and prosecutors thought that they were too violent or had too many pending charges to be offered a second chance. The remaining 12 dealers were each sent a letter explaining that they had been the subject of an undercover investigation, and that they were invited to a "call-in" where they would be offered help in exchange of quitting dealing. "You will not be arrested," the letter read. "This is not a trick. You will receive a one-time offer of help and hear how the rules are being changed for you."

On May 18, 2004, nine of the invited 12 dealers showed up. They were shown the evidence against them, as well as arrest warrants lacking only a judge's signature. Pictures of the men who had already been arrested were taped to empty chairs. The police informed them if they stopped dealing immediately, they wouldn't be arrested, but if they were caught again, they would be zealously prosecuted.

Social workers, ministers, family members, and other citizens were also at the call-in to share the message that the community cared about the dealers, but that it would no longer tolerate their behavior. The HPCAV offered to help them connect with social services or job training programs.

The gamble the police and the community were making was that the dealers would respond rationally to the change in their cost-benefit calculation. Before the meeting, the dealers perceived the risk of being caught as very small; low-level drug dealers can conduct hundreds of transactions between arrests. But now, the dealers were being told that they would be arrested and they would go to prison. "They had to make a different decision when they left there that night. They couldn't walk out of here and go right back to work tomorrow," says Sumner.

The calculation changed for Myres, who was part of a 2010 initiative in the Washington Drive neighborhood. "You've got to weigh out your options," he says. "So I just walked out and started a new day."

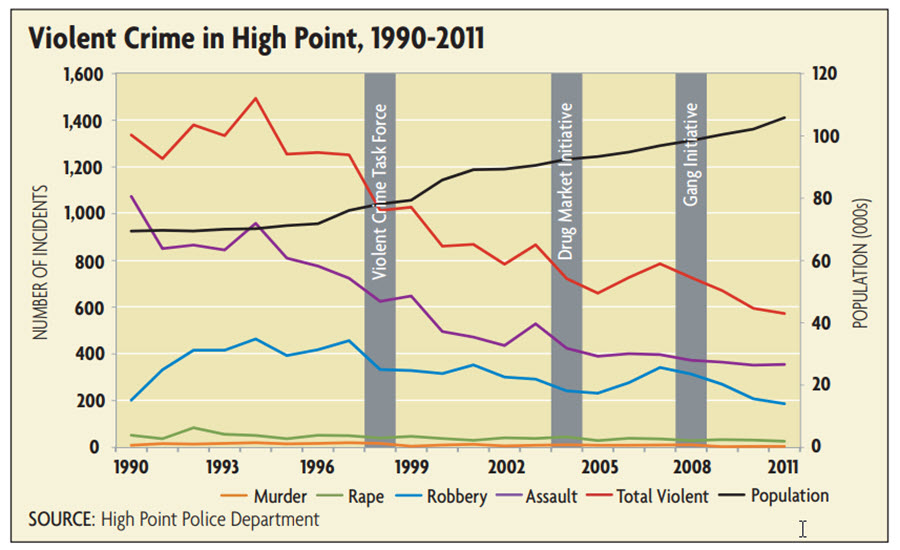

He wasn't the only one — the West End drug market closed down overnight. One hundred days after the call-in, violent crime in the West End was down 75 percent; four years later, it was still down 57 percent. Over the next six years, High Point repeated the intervention in four additional neighborhoods with the same success. Citywide, the number of violent crimes has decreased 21 percent since 2004, even though the population has increased 14 percent. (See chart below.) The recidivism rate among called-in dealers is about half the North Carolina average. (In 2008, the city saw an uptick in violence that was associated with gangs; the police re-enlisted Kennedy's help to develop a focused deterrence program for gang violence and saw the crime rates come back down.)

Before the initiative, some feared that the drug markets would simply reopen in other parts of the city. But there are several reasons that hasn't happened, according to Sumner. First, most of the customers were people who drove in from out of town. Once the market was gone, they couldn't wait around for it to be re-established. In addition, it takes years for the conditions to develop that allow an open-air drug market to take hold; it isn't the kind of business that can easily pick up and move.

Other cities that have tried the High Point model, such as Seattle, Nashville, Tenn., and Rockford, Ill., have had similar results. In Rockford, for example, nonviolent crime decreased 31 percent and violent crime decreased 15 percent following the drug market initiative. In the Fifth District, cities including Durham, N.C., Roanoke, Va., and Baltimore are currently undergoing training on the process.

A Nation of Inmates

Nationwide, however, incarceration is still the preferred method of law enforcement. The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world: About 720 people per 100,000 are in prison or jail, for a total of 2.3 million. (Prisons are operated by state governments and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Jails are operated by sheriffs and local governments and are designed for people awaiting trial or serving short sentences, typically under one year.) In Russia, the rate is 477 per 100,000; in China, it's 121 per 100,000 (or 170 per 100,000 if people held in administrative detention are included). In most European countries, the rate is less than 150 per 100,000.

The rate hasn't always been so high; until the early 1970s, it was only about 100 people per 100,000. But in 1975, an influential study concluded that efforts to rehabilitate criminals were failures, a finding that helped to shift the goal of imprisonment from rehabilitation to simply incapacitation. At the same time, the country was ramping up its war on drugs and citizens wanted politicians to get tough on crime. Incarceration rates were further increased by the introduction of mandatory minimum sentencing in the 1980s and "three strikes" laws in the 1990s. As a result, the prison population has increased by about 500 percent over the past 35 years, compared with 45 percent for the population as a whole.

Maintaining that population is expensive: The average annual cost to keep a single person in prison is about $29,000 per year. In 2012, the Federal Bureau of Prisons spent $6.6 billion. The states spent nearly $50 billion on corrections in 2010, the most recent year for which data are available, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Spending time in prison is costly for the inmates as well. Prisoners disproportionately have low levels of education — about half haven't completed high school or its equivalent — and going to prison further decreases the likelihood that they will eventually earn a high school diploma or GED. Once they have been released, former inmates have lower earnings and higher unemployment rates than people with similar work experience and education, according to research by Becky Pettit at the University of Washington and Bruce Western at Harvard University. In addition to the fact that convicted felons are barred from working at many companies and government agencies, there is a strong stigma associated with prison, as Devah Pager of Princeton University has found. She sent pairs of fake job seekers out to apply for real jobs with identical resumes, except that one was randomly assigned to have a criminal record. The job seekers with records were 50 percent less likely to receive a call back from prospective employers.

High incarceration rates also affect entire communities, particularly black communities. Although black people make up 13 percent of the U.S. population as a whole, they are 37 percent of the prison population. One out of every nine black men between the ages of 20 and 34 is in prison, compared with one out of every 57 white men, according to Pettit and Western. "There are neighborhoods where virtually all the men end up going to lockup," Kennedy says. Not only does that create hardship for the women and children of those communities, it also can breed antagonism toward law enforcement, which makes it difficult to police those neighborhoods effectively.

Reducing that antagonism was a major goal of the High Point model, says Kennedy. "The initiative was designed to get rid of the overt drug market, in a way that didn't lead to all these men going to prison, and in a way that could reset relationships between the residents and the police."

From Drug Market to Suburb?

Resetting those relationships required the High Point police to change the way they respond to complaints. Previously, if someone called and said they thought there was a crack house next door, a detective would start investigating, but that investigation would be invisible to the person who made the call; the caller would think that the police were unresponsive. Now, an officer goes out, knocks on the door immediately, and maintains a visible presence until the issue is resolved. That puts criminals on notice, but perhaps more important, it creates a two-way street between the police and the community, with citizens involved in enforcing community standards. "I remember one community meeting where people wanted to take the police's head off," says Gretta Bush, president of the HPCAV. "But when the question was asked, 'How many times did you call the police?' nobody raised their hand. It really evened the playing field for the community to realize, it's just as much me and what I'm not doing."

Critics of the High Point model say that it doesn't actually solve the drug problem; it just pushes it underground. That's okay with Kennedy, who says that eliminating all drugs isn't the goal. Instead, it's to create basic safety and stability. "I know neighborhoods where young men are selling drugs and using drugs, but they're not carrying guns and they're not selling drugs on people's front lawns. And the name for those neighborhoods is the suburbs."

It's also true that despite the HPCAV's offers of help, most of the former drug dealers have not gone back to school or found jobs. But from the law-enforcement perspective, Sumner says, as long as the violence has stopped, the community has won, regardless of the outcomes for the individual dealers.

The former drug market neighborhoods have not turned into the suburbs. The people who live there are still poor; the homes have sagging porches and peeling paint, and unemployment is high. But some businesses have returned, and the city is tearing down former crack houses and building new homes. Where children once weren't allowed to go outside, a young girl pushes her baby sister in a stroller and a group of boys play basketball in the street. Myres has one word to describe the neighborhood these days: "Quiet."

Readings

Kennedy, David. "Drugs, Race and Common Ground: Reflections on the High Point Intervention." National Institute of Justice Journal, March 2009, no. 262.

Lee, David S., and Justin McCrary. "The Deterrence Effect of Prison: Dynamic Theory and Evidence." Center for Economic and Policy Studies Working Paper no. 189, July 2009.

Western, Bruce and Becky Pettit. Collateral Costs: Incarceration's Effect on Economic Mobility. The Pew Economic Mobility Project and the Public Safety Performance Project, September 2010.

Sites trained in the Drug Market Initiative by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Michigan State University School of Criminal Justice

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.