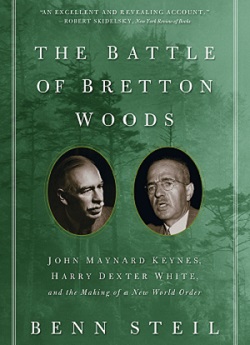

The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order by Benn Steil, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2013, 370 pages.

Benn Steil of the Council on Foreign Relations tells the story of the birth of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates at Bretton Woods, N.H., in July 1944. The United States had already decided on the design of the system in advance. At the actual conference, the American architect of the plan, Harry Dexter White, used his control of the agenda to railroad the American blueprint past the largely parochial and befuddled delegates from the 44 Allied countries represented. The United States wanted a system of international commerce that would allow unfettered access of foreign markets to its ascendant export industry. That meant restricting the ability of foreign countries to devalue their currencies relative to the dollar and to impose tariffs in order to advantage their own export industry.

The Battle of Bretton Woods makes this story of American power both engaging and instructive. It is engaging because of the way in which he portrays the competition over the design of Bretton Woods as a contest between two extraordinarily strong personalities: Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes. It is instructive because of the way in which he uses these two individuals to tell the intellectual history of the first half of the 20th century.

Keynes was 31 years old when, in 1914, the start of World War I brought an end to the international gold standard. The era of the gold standard had encouraged a "classical economics," which emphasized free trade and free markets. This intellectual orthodoxy associated the international gold standard and its free movement of gold and capital with free trade, laissez-faire, and the quantity theory. In the economic sphere, governments should give free rein to market forces.

In the 1930s, when the world economy crashed, so did support for classical economics among both public and professional economists. The demand was for government to master the destabilizing market forces that had presumably brought down the world economy. At the radical left end, intellectuals demanded central planning. White gravitated toward this end in principle. Keynes led the right end with his program to manage trade and the economy. Almost no one supported free markets.

The debate over the design of a postwar monetary system played out in this environment. There was a desire to return to the sense of security and stability that had characterized the earlier gold standard era. At the time, the consensus was that such stability required the fixed exchange rates of the gold standard. Earlier, Keynes, in his 1923 book A Tract on Monetary Reform, had pointed out that a country had to choose between internal stability of prices and external stability of the foreign exchange value of its currency.

A system of fixed exchange rates (providing for external stability) that precluded recourse to deflation (providing for internal stability) would then build in a fundamental contradiction. Keynes' design for the postwar system of international payments would have had fixed exchange rates but would have been made to work through "management" by technocrats to avoid deflation. Moreover, Keynes, like other contemporary observers, saw the capital outflows that forced countries on the gold standard, like Britain, into deflation and eventually into devaluations as evidence of the destabilizing influence of market forces rather than as symptoms of monetary disorder. Keynes' system would have allowed countries like Britain liberal use of devaluations against the dollar and exchange controls in order to deal with trade deficits. This discretionary "management" ran directly counter to the American agenda of wide open markets for American exporters.

In their capacity as negotiators, both Keynes and White pursued the agendas of their respective countries. In his capacity as British negotiator and in his own personal capacity, Keynes wanted to preserve what he could of the old system with London at the center of the world financial system. That meant resisting complete American hegemony. Debate then centered on two issues.

First, what would be the unit of account and the means of payment in the new system? The United States held most of the world's monetary gold. Also, every country after the war would need dollars to finance the imports required for basic commodities like food and energy and for reconstruction. The United States wanted a system based on gold and the dollar. Keynes wanted an entirely new paper currency, which he called bancor, a term combining the French words for bank and gold.

Second, Keynes did not want Britain to be completely dependent on American aid after war. To pay for its postwar imports, Britain would need to export. Keynes wanted Britain to be able to retain its imperial preferences, which restricted the ability of its colonies to import from countries other than Britain. Steil recounts how earlier in opposing the nondiscriminatory trade clauses contained in the Atlantic Charter, which would have ended the preferences, "Keynes exploded in rage in front of the State Department's Dean Acheson," reacting to the "lunatic proposals" of Secretary of State Cordell Hull.

The forceful, combative, yet complex personalities of White and Keynes provide a Technicolor background to the narrative. White wanted to be close to power to exercise influence. Completely apart from the role he played in securing the American agenda at Bretton Woods, White wanted to hasten a new economic order based on the Soviet model of state control. As summarized by Steil, based on an unpublished essay written by White, White believed that after the war the American economic system would move toward the Soviet model. Steil quotes White from the essay, "Russia is the first instance of a socialist economy in action. And it works!"

Keynes could be alternately charming and insolent. He referred to the negotiations at Bretton Woods as the "monkey house." He said of White, "He has not the faintest conception of how to behave or observe the rules of civilized intercourse."

In the end, Keynes knew that Britain would be dependent on American aid after the end of the war. During the war, Britain could not sustain its military without Lend-Lease. Assuring Lend-Lease meant cooperating with White, the U.S. Treasury, and the American demand for a postwar monetary order of fixed exchange rates and free trade. Keynes knew he had to accept the White plan and sell it to British politicians.

Benn Steil has written a book full of historical insight and human color.