Bottoms Up

Craft brewers raise the bar in the American beer industry

In many places across the country, it's hard not to notice the shift in product offerings at local bars and restaurants and in the beer aisle of the grocery store. The colorful, ornate tap handles of craft brewers have joined the classic blue, red, and silver posts of the traditional powerhouses, and bartenders play the role of consultant purveying the selections. Shoppers who once stood in the beer aisle trying to decide how many cans of beer to buy now stand in front of coolers filled with different brands and styles of beer available in single bottles, packs of four, six, or 12, and even on tap in a growing number of stores. Many of them have been made at a brewery down the street; according to the Brewer's Association (BA), the trade association that represents the craft beer industry, approximately 75 percent of the drinking-age population in the United States lives within 10 miles of a brewery.

In 2014, there were 615 new craft breweries that opened, pushing the number in the United States to 3,418, more than twice the number that existed just five years earlier. The BA defines a craft brewery as one that produces fewer than 6 million barrels a year, is less than 25 percent controlled by an alcoholic beverage industry member that is not itself a craft brewer, and produces a beverage "whose flavor derives from traditional or innovative brewing ingredients and their fermentation." The ownership restriction excludes the craft-style subsidiaries — such as Shock Top, Goose Island, Leinenkugel, and Blue Moon — of large brewers like Anheuser-Busch InBev and MillerCoors (the two largest brewers in the United States).

Although craft beer remains a relatively small segment of the market, accounting for only 11 percent of the beer produced in the United States in 2014, the segment is growing rapidly. Craft beer's share of production has more than doubled since 2010, when it was just 5 percent. In 2014, craft beer sales volume increased nearly 18 percent, according to the BA, versus just 0.5 percent for the overall beer industry. The retail dollar value of craft beer grew 22 percent in 2014, while the total U.S. beer market increased only 1.5 percent in value.

The growth of small breweries runs counter to the trend of consolidation in the beverage industry that persisted through much of the 20th century. Why are craft brewers thriving?

American Beer's Backstory

The recent growth of craft brewing is only the latest chapter in the centuries-old story of beer in America.

Americans have brewed and consumed beer for a long time, with production dating back to some of the first European settlers in the mid-1600s. Before the Civil War, beer was mostly British-style ales or malts that were brewed locally, stored in a wooden keg, and consumed in the local tavern. In the years following the Civil War, beer became an industrial product that was mass produced and widely distributed.

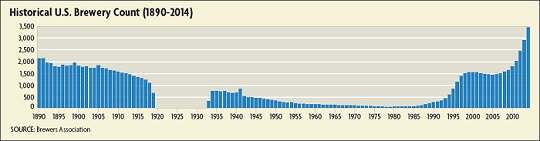

This change resulted in part from the large inflow of immigrants from beer-drinking countries such as Germany and Ireland, who brought both new styles of beer and a beer-drinking culture. Higher wages for some workers and the technological advancements that accompanied industrialization also helped fuel growth in aggregate beer consumption and production. In 1865, 2,252 breweries supplied 3.7 million barrels of beer annually to Americans, who consumed 3.4 gallons per drinking-age adult. By 1910, a total of 1,568 breweries produced 59.6 million barrels, and the consumption rate had increased to 20 gallons per drinking-age adult.

The aggregate picture of the American beer industry during this chapter hides crucial brewery-level decisions that helped shaped the modern American beer industry. In the late 19th century, for example, some breweries decided to leverage the growing transportation network and new technologies, such as pasteurization, bottling, and refrigeration, to expand their product reach beyond what they could sell from their own establishments. When Prohibition was enacted in 1920, these firms were relatively less inclined to sell off their assets and cease operations than their smaller competitors. They decided that rather than divest from the brewing business altogether, they could stay in business by producing near-beer malt beverages, sodas, and syrups. While Prohibition was in effect, these firms were perfecting beverage bottling and packaging processes, developing relationships with retailers, gaining marketing experience, and improving manufacturing processes to achieve economies of scale. By the time Prohibition was repealed in 1933, they were much better situated to resume beer production than their former competitors.

Craft Beer in the Fifth District

A web-exclusive look at recent developments in the craft beer industry in the Fifth District.

Prohibition changed the market in other ways as well. Prior to Prohibition, most breweries sold their beer on draft in saloons they either owned or controlled; temperance advocates believed this system contributed to the overconsumption that led to Prohibition. As a compromise reached during the repeal, a three-tier system was adopted: Brewers would now sell their beers to an independent wholesaler who would then sell the beer to independent retailers. The introduction of a middle-man to the market structure had several effects. First, it protected retailers from pressure from larger brewers to only sell certain products. Second, it provided small brewers with better access to the consumer, as the wholesaler would provide distribution equipment, marketing, and sales expertise — costs that could be barriers to entry for many small players. Finally, wholesalers made it easier for the government to tax alcohol and monitor overall alcohol consumption.

In the years immediately following the repeal, many breweries attempted to resume operations; the number of legal breweries rose to around 850 in 1941. But the three-tiered system that helped small brewers in some respects wasn't enough to erase the advantage held by the firms that rode out Prohibition making syrups and malts. In addition to the experience they had gained, these firms did not have to incur the fixed costs associated with opening a brewery.

After Prohibition, there was a huge unmet demand for beer. According to economists Eric Clemons and Lorin Hitt of the University of Pennsylvania and Guodong Gao of the University of Maryland, this demand could best be met by mass producing standardized products. As they wrote in a 2006 article, all the major producers of the time "followed Anheuser-Busch [which was founded in 1862] in a race for scale-based, quality production of largely undifferentiated products." Rather than creating truly differentiated products, large producers created barriers to their competitors "through massive marketing and advertising investments intended to create perceived differentiation for otherwise similar products."

As a result, advertising became a major cost component in the production of beer and forced smaller brewers out of the market. The American beer market consolidated from the end of World War II to 1980. By that year, just 101 firms were producing 188.4 million barrels of mostly American-style lager and drinking-age adults consumed an all-time high of 23.1 gallons per year.

Craft Beer Comes to a Head

With domestic beer production heavily skewed toward light lagers, other styles of beer that were no longer being produced domestically had to be imported. From 1950 to 1972, the quantity of beer imported annually by the United States grew from less than 100,000 barrels to about 1 million barrels. Then, in October 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed a bill that legalized home brewing and shortly after, individual states began legalizing brewpubs — restaurant- breweries that sell 25 percent or more of their housemade beer on premise. The craft brewing segment was born.

In the early 1980s, there were only eight craft brewers in the country. They found a foothold in the market by producing beer other than lagers and thus did not compete directly with the non-craft brewers. From 1980 to 1994, the number of craft breweries nationally rose to just over 500. Then, the craft beer industry began its first major boom, growing rapidly through the end of the decade; the number of breweries nearly tripled to 1,509 in 2000. Many of these breweries were very small, however, with annual production levels of between 5,000 and 100,000 barrels, according to economist Martin Stack of Rockhurst University. As a result, the market was still highly concentrated, with the three largest producers at the time (Anheuser-Busch, Miller, and Coors) accounting for 81 percent of the domestic supply. In the early 2000s, the number of craft brewers slowly but steadily declined — perhaps as a result of "over-exuberance," as economists Victor Tremblay, Natsuko Iwasaki, and Carol Tremblay of Oregon State University wrote in a 2005 paper. In other words, the first entrants may have proved the viability of the industry, which began a cycle of entry, success, and further entry that exceeded the market's capacity, leading to the eventual exit of some players. But by 2008, craft beer was again on the rise. The number of craft breweries nationally reached 3,418 in 2014, more than double the number reached during the previous expansion.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.