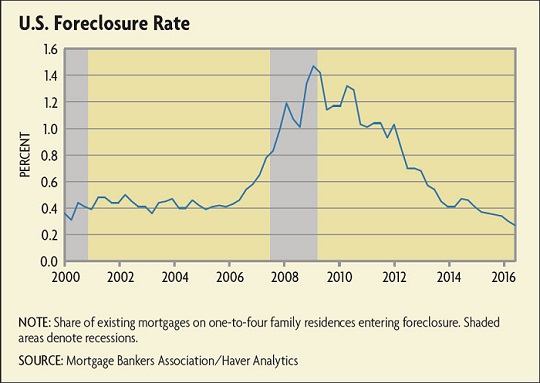

Initially, defaults were concentrated in the nonprime and nontraditional market segments. But as more homeowners became underwater on their mortgages and job losses increased, prime borrowers were affected as well. "The first wave of foreclosures was subprime mortgages blowing up," says Nela Richardson, chief economist for the national real estate brokerage Redfin and a former researcher at Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies. "The second wave was the economic downturn. Borrowers were upside down on their loans and then they lost their jobs — and maybe their health insurance and their kids' college funds. It was a double or triple whammy."

All else equal, subprime borrowers were more than twice as likely to lose their homes to foreclosure or short sale, according to a 2015 paper by Fernando Ferreira and Joseph Gyourko of the University of Pennsylvania. But the authors also found that about twice as many prime borrowers as subprime borrowers wound up experiencing a foreclosure or short sale. That's because prime borrowers still made up the majority of the housing market despite the rise of subprime lending.

Black and Hispanic borrowers were more likely to enter foreclosure than white borrowers. Among borrowers who purchased homes between 2005 and 2008, nearly 8 percent of black and Hispanic borrowers had lost their homes to foreclosure by the end of 2009 versus 4.5 percent of white borrowers, according to a 2010 study by the Center for Responsible Lending, a consumer advocacy group. Blacks and Hispanics also were more likely to be seriously delinquent on their mortgages. The disparities became smaller, but did not disappear, after the researchers controlled for income levels. In a 2016 article, Ferreira, Patrick Bayer of Duke University, and Stephen Ross of the University of Connecticut also found significant racial and ethnic differences in mortgage outcomes, even between borrowers with similar credit scores and loan characteristics. The source of the disparity could be minorities' greater vulnerability to unemployment during economic downturns combined with the timing of their entry into the housing market.

Intuitively, investors should be more likely to default on their mortgages than owner-occupants, since "there's very little reason not to default on an investment property loan if it's offering a negative return," says Haughwout. "It's one thing to move your family if you're underwater — that's very costly. But it's another thing entirely to let go of a property that's not a good investment."

The evidence on investors' propensity to default during the crisis is mixed, however. On the one hand, Ferreira and Gyourko found that investors were about as likely to experience a foreclosure or short sale as owner-occupants with similar loan types and amounts of leverage. On the other hand, Haughwout and his fellow New York Fed economists found that investors' delinquency rates in the nonprime sector increased more rapidly than owner-occupants' rates, and that by 2008 investors' share of seriously delinquent nonprime mortgage debt exceeded their share of overall mortgage debt. Consistent with Ferreira and Gyourko, they also found that some of the difference between investor and non-investor delinquency rates was related to the fact that investors were more likely to take out loans with a greater initial risk of default, for example, because they were in the sand states or had higher leverage. But about half of the difference remained unexplained, which suggests investors might indeed have taken a more pragmatic approach to default than other homeowners with similar characteristics.

Bouncing Back?

Homeowners who enter foreclosure take a serious hit to their credit. According to Fair Isaac Corp., the FICO score's developers, a borrower with a credit score of 780 usually can expect to drop between 140 and 160 points; one with a score of 680 can lose 85 to 105 points, assuming there are no other delinquencies. (Short sales, deed surrenders in lieu of foreclosure, and most loan modifications have a smaller but still substantial negative effect.) During the foreclosure crisis, however, borrowers who lost their homes experienced even larger declines — 175 points on average for prime borrowers, and 140 points on average for subprime borrowers according to a 2016 Chicago Fed Letter by Sharada Dharmasankar of the consulting group Willis Towers Watson and Bhashkar Mazumder of the Chicago Fed.

By law, many negative credit events, including foreclosure, are removed from individuals' credit records after seven years. In principle, then, borrowers who experienced a foreclosure in 2007 should have seen their credit scores recover in 2014 and successive waves of borrowers in the years following. In a 2015 report, the foreclosure analytics company RealtyTrac estimated that 7.3 million people would have their credit sufficiently repaired to buy homes over the next eight years. Other trade groups and analysts also calculated that millions of former homeowners would have the credit to become homeowners again in the coming years. That prompted speculation that a wave of "boomerang buyers" was poised to re-enter — and reignite — the housing market. In the same report, RealtyTrac called these former homeowners "a massive wave of potential pent-up demand."

But history says not all those buyers are likely to come back. According to a 2016 study by CoreLogic, fewer than half of those who lost a home in 2000 or later have purchased new homes, even among those 16 years past a foreclosure.

The boomerang rate has been especially low so far for people who lost their homes during the crisis. A little over 30 percent of borrowers who lost their homes in 2000 had purchased another home seven years after the event. But only about 15 percent to 20 percent of borrowers who lost a home between 2006 and 2008 had returned to the housing market after seven years. Dharmasankar and Mazumder found similar results. Within seven years of a foreclosure that occurred between 2000 and 2006, about 40 percent of prime borrowers and 30 percent of subprime borrowers had purchased another home. But among borrowers who experienced a foreclosure between 2007 and 2010, only 25 percent of prime borrowers and 17 percent of subprime borrowers were homeowners seven years later.

Once Bitten, Twice Shy

A variety of factors could explain why homeowners (both owner-occupants and investors) who experienced foreclosure during the most recent crisis have been slow to return to the housing market. First, foreclosure generally is not an isolated incident; consumers tend to have higher delinquency rates on other forms of credit after a foreclosure than they did before the foreclosure. "It's not very common that all your credit is fine except for the foreclosure," says Haughwout. "And once you've experienced a foreclosure, the interest rate increases on your other debt, and it becomes harder to keep up with. The foreclosure has a deleterious effect for years."

The foreclosure crisis and Great Recession might have been particularly damaging financially. At least through 2011, borrowers who lost their homes between 2007 and 2009 had higher delinquency rates on credit cards and auto loans than borrowers who lost their homes in the early 2000s, a similar length of time after the foreclosure, according to a 2010 paper by Cheryl Cooper and Kenneth Brevoort of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and subsequent research by Brevoort. Dharmasankar and Mazumder found that the credit scores of people who went through a foreclosure between 2007 and 2010 have been slower to recover than those who had a foreclosure between 2000 and 2006. Prime borrowers have been especially slow to regain their former scores since they have a higher score to return to.

As of 2016, previously foreclosed homeowners who had not returned to the housing market had significantly higher delinquency rates and lower credit scores than those who had returned, according to research by Michele Raneri of Experian. They also had higher delinquency rates than the U.S. average, which suggests continuing credit problems could be a hindrance for some former homeowners.

Tighter lending standards could also be preventing some people from re-entering the housing market. To the extent some borrowers were able to obtain larger or riskier mortgages during the boom than they would have at other times, that may reflect a prudent amount of risk-taking by lenders. Still, there might be some creditworthy borrowers who would like to purchase a home but cannot. Although mortgages currently are easier to obtain than they were in the years immediately following the crisis, when lenders drastically curtailed lending, mortgage credit during the first quarter of 2017 was only about one-half as available as it was in 2004, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association's Mortgage Credit Availability Index. In addition, many potential homebuyers perceive that they would be unable get a loan. According to the New York Fed's 2016 Survey of Consumer Expectations Housing Survey, nearly 70 percent of current renters thought it would be very difficult or somewhat difficult for them to obtain a mortgage.

"The market the boomerang buyers bought into the first time around doesn't exist anymore," says Richardson.

Some borrowers who could re-enter the housing market might not want to. Particularly for owner-occupants, research points to deep emotional scars from experiencing a foreclosure, which could affect one's willingness to purchase a home again. Also, many of the people who lost their homes during the crisis were first-time homebuyers, and there is some evidence the crisis altered their views about the prudence and benefits of homeownership, at least in the medium term. As of December 2014, the credit bureau TransUnion estimated that about 1.26 million previously foreclosed consumers had recovered enough financially to meet strict underwriting standards. Of them, only 42 percent had taken out a new mortgage.

Investors might be less sanguine about real estate as an investment strategy. Raneri also found that between 40 percent and 45 percent of investors (including second-home owners) who went through foreclosure between 2001 and 2006 returned to the market. The share for those who experienced a foreclosure between 2007 and 2010 was between 16 percent and 19 percent. (The lower share could reflect in part that 2010 foreclosures had not been erased from credit reports.) The number of people flipping houses is also significantly lower than it was during the boom. In 2005, more than 275,000 investors flipped 340,000 homes, or 8.2 percent of sales, according to ATTOM Data Solutions (which operates RealtyTrac). In 2016, 125,000 investors flipped fewer than 200,000 homes, or 5.7 percent of sales. That's a slight increase from 2015, but overall the number of homes flipped has been relatively flat since 2010.

By some measures, the housing market looks quite strong. In many areas of the country, house prices have rebounded to their 2006 peak and the length of time homes remain on the market has declined. But this in part is the result of low inventory; new housing permits and new home construction starts have increased since 2010 but are low by historical standards. This relative lack of supply could be preventing some former homeowners from boomeranging. "We're in a seller's market,"says Richardson. "And there are a lot of cash buyers who are able to make sizeable down payments. That curtails the ability of boomerang buyers to make a successful bid in this market."

Does Homeownership Matter?

The U.S. homeownership rate, defined as the percentage of households who own the home they live in, was 63.6 percent in the first quarter of 2017, compared to the peak of 69.2 percent in 2004. Since the Census Bureau began keeping track, the lowest recorded value was 62.9 percent in 1965.

At first glance, it might seem that the increase in the homeownership rate during the early 2000s was driven by the expansion of mortgage credit to certain categories of borrowers, and that the decline is the result of these borrowers losing their homes. But the increase in nontraditional and nonprime loans does not seem to have had much effect on the homeownership rate. In part, that's because the increase might have helped people obtain bigger mortgages than they otherwise would have rather than pushing them into homeownership to begin with. And to the extent the expansion of credit did increase the number of homeowners, it still might not have had a large effect since the owners of rental homes or other investment properties aren't counted in the homeownership rate. "After 2004, many new purchases were by speculative investors," says Haughwout. "There was a lot of buying and selling that didn't have anything to do with the homeownership rate."

In large part, the rise in the homeownership rate through 2004 reflected the aging of the U.S. population, since older adults are more likely to own their homes, according to research by Haughwout and fellow New York Fed economists Richard Peach and Joseph Tracy. And much of the decline since then is the result of a secular decline in homeownership for young and middle-aged adults, particularly those aged 25-54, a trend that backs to the 1980s. (The remainder does seem to be due to people who left the market via foreclosure.) Multiple factors could explain this decline in homeownership, such as declining real incomes for some groups or changes in preferences. Whatever the cause, it suggests that even if many more buyers boomeranged, the homeownership rate would be unlikely to return to its pre-crisis peak.

Does that matter? For someone trying to buy or sell a home, the answer surely is "yes." But for society as a whole, the answer is less clear. Some studies point to large social externalities; homeowners may have stronger incentives to maintain their homes and neighborhoods and invest in their community's civic and social lives. But it's difficult to establish a causal link between homeownership and community engagement. It could be that people who are more likely to plant attractive landscaping or vote for school board members are also more likely to buy homes rather than homeownership inducing those actions. And in some ways, homeownership might actually have negative effects, such as making labor markets less flexible if it is more difficult for people to move for new employment opportunities.

The housing market is a vital part of the U.S. economy. Increases in residential investment, including new homes and remodeling, generate a lot of jobs — not only in construction, but also in real estate, finance, and transportation, to name just a few industries. Moreover, rising home prices create a wealth effect that enables many households to fund consumption. Some economists and policymakers thus pointed to the sluggishness of the housing market after the recession as a factor contributing to slower-than-desired economic growth. If potential boomerang buyers remain on the sidelines and current trends in homeownership continue, it's unlikely that housing activity will return to the levels of the boom years — or that it will make as large a contribution to GDP growth. But to the extent the economy is in the process of adjusting to a sustainable level of housing activity, that may be an unavoidable cost.