How Anecdotes Inform the Fed

Conversations with business and community leaders can shed light on the economy when data lag

Sometimes, the economy moves faster than the speed of data. This year, for instance, a slew of federal policy changes, including large tariff increases, has had cascading effects on the economy and introduced an aura of uncertainty. The impact of those tariff increases is unlikely to show up in official data for months; it takes time for the ripple effects to make their way through the supply chain and into the pricing decisions of companies and consumption decisions of households. For Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin, this is where the Richmond Fed's on-the-ground outreach comes in.

"We talk to businesses nearly every day. It's incredibly valuable. For example, in recent months, we've been asking: 'How are you thinking about the new tariffs? Are you looking at changes to your supply chain? Will you pass on the costs?'" says Barkin. "We get to see how business thinking and planning evolves in real time, which helps us better anticipate how economic conditions will change in the months to come."

The Fed uses a variety of hard data to inform monetary policy decisions in order to effectively fulfill its dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment. But qualitative, real-time information has become increasingly important for providing insights into the economy. The way that the Federal Reserve Banks collect and prioritize that data has evolved as well.

Filling in the Gaps

Quantitative data provide economists with a broad picture of the economy's health. But external shocks to the economy, such as a major policy shift or a global health crisis, can create a rapidly changing environment that is not immediately reflected in backward-looking datasets. There is always a lag — often a month or more — between the period of reference and when data are published. Many economic indicators are also composed of preliminary estimates and incomplete information, so after periods of rapid change or unexpected shocks, data are often revised significantly.

Qualitative information can be especially helpful at filling in the gaps during periods where data are changing rapidly or sending conflicting signals on the economy's health. While monetary policy decisions aren't made solely based on qualitative information, it can supplement hard data by providing a timelier snapshot of the economy at a particular moment, helping policymakers to forecast ahead.

"Data doesn't show the future, but people do," says Urvi Neelakantan, a senior policy economist at the Richmond Fed. "You can always ask contacts about their plans, what's happening in the next three to six months. Hard data are rarely current — the earliest data you have in June is from May, so if there is anything that's happened in the meantime, the only way you are going to hear about that is through sensing."

Sensing on the economy is any interaction, no matter how informal, that provides an insight into the ways people or businesses are making decisions or into the economic environment in which decisions are made. For instance, a conversation with a cashier at a convenience store could involve questions about foot traffic. Are they restocking as usual? Are customers buying store brand snacks or opting not to splurge on impulse treats at all? A conversation with a consumer packaging firm may provide a line of sight into future consumer demand, and a manufacturer might provide an explanation as to whether a surge in inventory is a result of negative demand or frontloading in anticipation of an increase in sales.

Each interaction contributes to an aggregate picture about changes in demand, pricing, consumer spending, and labor tightness — all standard economic indicators measured through larger scale surveys and macroeconomic datasets. This type of sensing differs from formal surveys because the sample size is smaller, so expertise and context is required to extract signal from the noise and to judge the extent to which anecdotes are representative. The flip side is that the information received can be richer, providing the "why" behind data movements and thus where things may go in the future. Further, where surveys often capture cursory responses to specific questions from anonymous participants without opportunity for follow-up, economic sensing involves reciprocal sharing that allows both Fed staff and their contact to validate theories and pursue greater context around salient observations. Both sides benefit from hearing the other's perspective on economic conditions.

Capturing Regional Variation

The 12 Reserve Banks were originally created to facilitate the supply of money throughout the country. Over the last 100 years, the roles, functions, and operations of the Reserve Banks have evolved, but the decentralized structure of the system has been preserved.

In the midst of the Great Depression, banking regulation and monetary policy setting authority was overhauled and consolidated into the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). This policymaking body, still structured the same way today, balances the perspective of a central authority — the Washington, D.C.-based Board of Governors that oversees the Federal Reserve System — with regional representation from independent Reserve Bank presidents who curate individual viewpoints on the overall economy and the best course for monetary policy.

While only five regional bank presidents have voting privileges at any given FOMC meeting, all 12 are responsible for sharing insights about their district's economy. From the earliest FOMC meetings in the 1930s, qualitative data from each district gathered through relationships with businesses and communities were presented to the full committee to inform monetary policy decisions. Through the years, improvements in the availability and analysis of economic data through modeling, forecasting, and surveys have advanced the Fed's ability to respond to shifts in economic activity. But the presentation of regional perspectives, including anecdotal information from regional bank presidents, remains a key component of each FOMC meeting.

Since the early 1980s, regional, anecdotal intel collected by the 12 Reserve Banks has been made available to the public via the Beige Book. Before each FOMC meeting, regional Reserve Banks submit a summary of qualitative information gathered from surveys and interviews with contacts in their district to the Board of Governors. Most often, those contacts are in bellwether industries that have a large influence on the overall economy, such as real estate, retail, shipping logistics, and banking. Enabling public access to that information has made the Beige Book a key source of real-time information on regional economic conditions for a variety of business and community decision-makers.

Charles Gascon and Joseph Martorana of the St. Louis Fed are the latest researchers to analyze whether the Beige Book indicates turning points in the economy before they show up in the data. They looked at changes in economic sentiment, political shocks like wars or labor strikes, and physical shocks like natural disasters and found that over its 50-plus year history, the Beige Book has captured statistically useful information about the U.S. business cycle in real time.

"While we still have to see what comes out in the data, anecdotes help us understand what direction the data are headed and why," says Gascon. "Being able to tell a story about the data matters."

Signaling Turning Points

Transcripts of FOMC meetings (made public with a five-year lag) provide further evidence that soft data like that published in the Beige Book can supply an early indication of economic shocks, giving monetary policy decision-makers a longer runway to consider impending challenges.

For example, excerpts from the Oct. 30-31, 2007, FOMC meeting illustrate one crossroads when anecdotes painted a different picture than quantitative data. Throughout the prior year, many committee members had been elevating informal intel from contacts in their districts suggesting that vulnerabilities in the housing market could have wider implications for the overall economy. The Fed cut interest rates for the first time in September 2007 in response to the housing fallout that, at the time, was perceived as an isolated tremor. At the October meeting, then-St. Louis Fed President William Poole shared how sensing was reshaping his views on the appropriate monetary response.

"Two weeks ago I was pretty adamant in my own mind that the recommendation I would be offering was no change, but I have reluctantly tilted in the other direction and favor a 25 basis point cut," shared Poole in his district statement. "I have changed my mind because ... in my discussions with our directors, in my phone calls before the meeting, and around the table yesterday, I think there has been fairly pervasive anecdotal information indicating a soft economy — not disastrously weak but just soft, certainly softer than the hard data that have been coming in."

And Poole was not alone in his pivot on the appropriate policy response.

David Stockton, the Board of Governors economist responsible for presenting cyclical estimates of GDP, inflation, and unemployment, conceded that there were "still some touchy-feely kinds of things that we're looking at," referring to additional surveys of Beige Book contacts that led his team to adjust its forecast. "Those anecdotes gave us a little more confidence that something may be happening on the capital spending side going forward."

Other Reserve Bank presidents shared anecdotal insights from their districts, like CEOs lamenting difficulty controlling inventories due to soft consumer demand, banks indicating credit card usage had declined, department stores noting sales were down, and general signs of spillover into the rest of the economy. These exchanges happened months before the empirical measures of a recession, defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research as "a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months," actually showed up in hard data.

Since the Great Recession of 2007-2009, the Board of Governors has prioritized engagement with public stakeholders through an event series called Fed Listens as a way to hear how monetary policy affects their daily lives. At one such event at the St. Louis Fed in April, Gov. Christopher Waller remarked that "the Federal Reserve was, in important ways, actually designed to promote this kind of engagement and input from the public."

Waller, who previously served as the director of research at the St. Louis Fed, spent a lot of time tracking data indicators about inflation and the job market in the Eighth District, but said he "learned just as much about how important it is to hear from people directly about their experiences as well as their perceptions, which are sometimes just as consequential for the economy. We call this part of the 'soft' data that supplements the hard numbers of the government statistics that policymakers eagerly await. The 'hard' data is indispensable for setting monetary policy, but we can't get a full and detailed picture of the economy without the soft data you can provide."

Sensing Evolves

The Beige Book remains the central source for anecdotes collected across the Fed System, but many Reserve Banks have formalized additional input mechanisms and processes to collect and deploy economic insights. Public engagement allows the Fed to better communicate with local stakeholders about the economy and how monetary policy decisions are made, as well as better evaluate the real economy across different sectors and regions. That matters because the regional economies of each Reserve Bank's district are impacted differently by the Fed's actions. For example, there was a perceived difference in how the Great Recession affected national financial sector stakeholders and the local public.

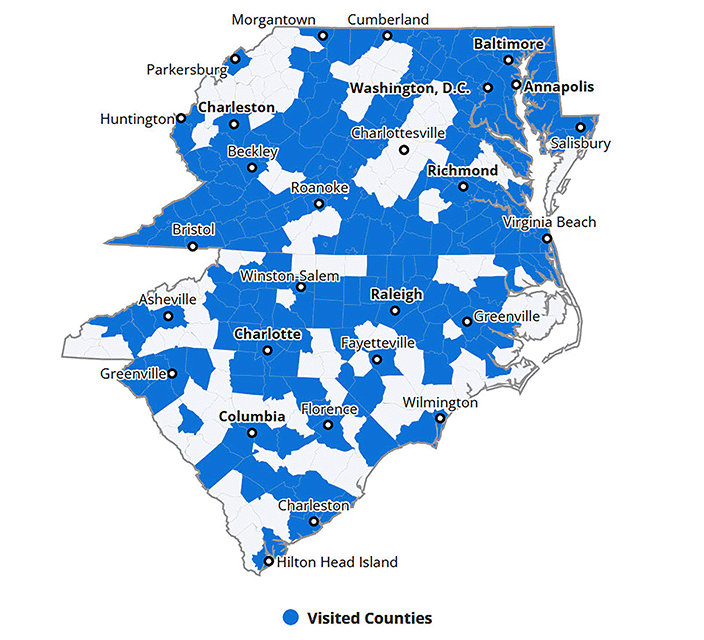

"The distance between Wall Street and Main Street is about three weeks," reflects Matt Martin, a regional executive at the Richmond Fed who helps lead business outreach in North and South Carolina. At the time, it was not well understood by the public how quickly the financial crash would spiral throughout the economy, nor how long the recovery would take. In the wake of that crisis, Martin says Reserve Banks expanded their public stakeholder relationships because "the more people understand who we are and what we're about, the better we can support our mission, our goals, and our congressional mandate. But we want it to be a two-way street, to give information back."

In recent years, the Richmond Fed has significantly expanded its outreach and engagement functions to enhance anecdotal information collection and support in-house research and analysis. Through a collaborative economic sensing process, outward-facing staff work alongside economists to turn both qualitative and quantitative data into useful insights about the economy. Direct engagement on the ground through business and community outreach, industry roundtables, external events, initiatives, and partnerships all yield anecdotes about real-time trends from multiple perspectives. That intel is shared back internally, synthesized, and evaluated for ways it can inform monetary policy decision-makers, researchers, and the public. Macroeconomic research has also evolved to better use qualitative information.

"Now, more data allows us to better inform economic modeling and, in particular, to build from the ground up in a way that couldn't easily be done 20 years ago," says Pierre-Daniel Sarte, senior macroeconomic advisor at the Richmond Fed. "Through our colleagues' interactions with contacts on the ground, we can better understand interconnections in the economy — how different sectors and industries interact with one another, how they make business decisions and so on."

"I believe one of the best moves you can make is to surround yourself with people who know more than you. When the goal is to really understand a community, no one has more expertise than the people who live and work there every day," says Barkin.

Stories Not Captured in Aggregate Data

Direct engagement in his district helps Barkin understand the economy in real time, and it also solves some challenging data limitations. Nearly one-quarter of the Fifth District's population lives in small towns or rural areas where economic data is time-consuming to collect, difficult to construct or estimate reliably, and often does not exist at the granular levels necessary to do meaningful economic analysis. Just because rural areas can be harder to understand using aggregate data does not mean those regions are not important to the economic vitality of the Fifth District. The Richmond Fed has placed a strategic focus on rural communities to better understand their unique economic challenges and assets compared to urban and suburban counterparts.

Part of that focus has included initiatives like Community Conversations, where Barkin, regional executives, and community development staff visit dozens of small towns each year to learn directly from local leaders and businesses about their strengths and exchange ideas about opportunities for growth.

These regional or sectoral differences are not always relevant to monetary policy, since its goals concern the overall economy, and interest rates are known as a "blunt tool" affecting the whole economy at once. But as the Richmond Fed learns deeply about its district, it shares that information broadly to help other decision-makers seeking to support the economy, sectors, regions, or communities. For example, in a recent speech, Barkin summarized insights from the ground about why certain rural communities grow when others don't and what they can learn from one another.

Data alone do not always tell the full story of the economy. Economic researchers understand that there are trade-offs to using any one data source, and anecdotes can fill in the gaps between retrospective quantitative data collected at set intervals and the economic activity that happens in the margins. Today, on-the-ground sensing is helping economic decision-makers like Barkin understand how tariffs and other changes are impacting his district and their implications for monetary policy. At a roundtable with Durham, N.C., business leaders in May, Barkin took on the role of an "economic detective," according to a report in the Wall Street Journal, investigating how decisions are being made about price increases and labor in real time, gaining insight into what might show up in data months down the line.

Readings

Assanie, Laila, Ethan Dixon, and Emily Kerr. "Has the Beige Book Become Disconnected From Economic Data?" Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, May 27, 2025.

Bobrov, Anton, Rupal Kamdar, Caroline Paulson, Aditi Poduri, and Mauricio Ulate. "Do Local Economic Conditions Influence FOMC Votes?" Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter No. 2025-13, June 2, 2025.

Filippou, Ilias, Christian Garciga, James Mitchell, and My T. Nguyen. "Regional Economic Sentiment: Constructing Quantitative Estimates From the Beige Book and Testing Their Ability to Forecast Recessions." Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary No. 2024-08, April 16, 2024.

Gascon, Charles S., and Joseph Martorana. "Quantifying the Beige Book's 'Soft' Data." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis' "On the Economy" blog, Jan. 7, 2025.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.