South Carolina's Globalized Economy

Driven by the auto industry, the Palmetto State is a global economic player. How will tariff uncertainty impact its businesses?

When John Lummus moved to Greenville, S.C., from his nearby hometown of Anderson in 1995, he says there were only three restaurants where he could go for lunch in the downtown area. Today, he has his pick of 238.

"The growth is just phenomenal, and that's happened because manufacturing companies have come in, providing jobs and building wealth," says Lummus, president and CEO of the Upstate SC Alliance, northwest South Carolina's economic development organization. He points to companies from across the United States and around the world that have come to call this western corner of South Carolina home, including defense contractor Lockheed Martin, global textile and chemical producer Milliken, French tire giant Michelin, and German luxury carmaker BMW. There are over 1,100 international firms alone in South Carolina, according to the state's Department of Commerce. They employ over 170,000 workers and account for 10 percent of private industry employment.

"These are companies that can be anywhere in the world," he says, "but they've decided to locate here."

A great deal of that wealth and growth — not just in Greenville, but across much of South Carolina — is the result of international trade, as these firms and others buy parts and supplies from abroad and sell many of their finished products on the international market. In 2024, for example, South Carolina exported $38 billion in goods, accounting for 11.6 percent of the Palmetto State's GDP. Manufactured products made up nearly all of that total ($37.2 billion). Foreign companies aren't the only active exporters: A total of 6,261 companies in the Palmetto State sent products abroad in 2023, and 84 percent of them were small- and medium-sized companies with fewer than 500 employees.

Transportation equipment, such as cars and tires, accounted for $19.2 billion of South Carolina's exports in 2024, making it the largest manufacturing export category. In other words, more than half the value of all manufactured goods exported out of South Carolina came from automobiles and automobile-related products. Many of these products require inputs made overseas and imported into the state; automobile parts, including engines and transmissions, accounted for over $3.5 billion in imports.

In April, the United States announced new tariffs on imported goods from every country. Any meaningful increase in tariffs can significantly alter how companies in South Carolina relying on trade do business, forcing some to adjust where they source products and others to rethink where to sell their finished goods. In recent months, the government has frequently adjusted tariffs, leaving firms in a state of heightened uncertainty.

How did South Carolina become such a sought-after destination for international firms and a hub of trade activity? And how are firms across the state navigating a fast-moving and unpredictable trade environment?

Driving the Globally Integrated Economy

The transportation sector is a major element of South Carolina's modern, globally integrated economy, but cars were built in the state long before the likes of BMW and Volvo set up shop.

Just over the border from Charlotte, N.C., the city of Rock Hill was the home of Anderson Motor Co. from 1916-1926. Over the course of those 10 years, buggy maker John Gary Anderson produced and sold over 6,000 high-end cars, but, ultimately, his company was unable to compete with the carmakers that had established themselves in Detroit. The Michigan firms were able to thrive and grow, thanks in large part to the benefits of geographic clustering, or what economists call agglomeration effects. Economists Zhu Wang of the Richmond Fed, Luis Cabral of New York University, and Daniel Yi Xu of Duke University found in a 2013 working paper that inter-industry spillovers (that is, positive productivity and economic effects) from carriage and wagon manufacturers fostered the automobile industry's growth in Detroit and resulted in numerous "spinouts," where workers in one firm leave to create another firm in the same industry.

The modern auto industry in South Carolina began in 1973 when Michelin announced its first tire plants outside of France would be built in Anderson and Greenville, both in the western portion of the state. In the years since, Michelin moved its North American headquarters out of New York to Greenville, and it currently employs almost 10,000 people across 15 facilities. Since Michelin's arrival, Japanese tiremaker Bridgestone and German firm Continental Tire have also come to South Carolina. Today, the state produces 144,000 tires a day and exports more tires annually than any other state. The automotive cluster would take further shape the following year in 1974, when Bosch arrived in South Carolina and began producing fuel injection systems at its Charleston facility. Its presence has remained robust over the years, and the firm currently employs nearly 5,000 people in three locations across the state.

By the 1990s, automation and the availability of cheaper labor abroad had decimated textile manufacturing in South Carolina. Political leaders were keenly aware that if the state's economy was ever going to recover, they would have to bring in something new, and they began recruiting firms from elsewhere in the United States and abroad. In the late 1980s, then-Gov. Carroll Campbell reached out to German luxury carmaker BMW to ask if it might be interested in establishing a facility in the state. After the dollar declined relative to the deutsche mark, raising the price of cars made abroad, and U.S. sales dropped nearly in half from 1986 to 1991, BMW had to decide if it still wanted to sell cars here. The firm saw the significant market size, protections for U.S.-made cars, and a weak dollar all as reasons not just to remain committed to the U.S. market, but also to build those cars in the States. And South Carolina made an attractive bid, offering a 900-acre site worth $25 million near Interstate 85, a nearby international airport, and a rail line with direct access to the Port of Charleston. The firm would also have no property taxes, and it was given other incentives totaling over $130 million (nearly $300 million in today's dollars). BMW also preferred to be in the Eastern time zone, which allowed for easier communication with Germany.

"Tariff Update: Incorporating Recent Decisions and Deals," Economic Brief No. 25-23, June 2025.

"Supply Chain Resilience and the Effects of Economic Shocks," Economic Brief No. 25-02, January 2025.

"Competitors, Complementors, Parents and Places: Explaining Regional Agglomeration in the U.S. Auto Industry," Working Paper No. 13-04R, April 2013.

BMW would ultimately come to the town of Greer, just outside of Spartanburg, in 1992. A little over three decades later, the carmaker reported that it had invested over $14.8 billion in the state and brought in $26.7 billion in economic activity annually. Greer is its largest production facility globally, employing over 11,000 workers, and the company has grown into the largest car exporter in the United States by value, with over $10 billion in shipments abroad of luxury SUVs and coupes in 2024.

Other European carmakers would follow. In 2006, Mercedes-Benz began producing vans in Ladson, near Charleston, and employs over 1,600 workers. With BMW in the Upstate, Volvo opened its North American operations in Ridgeville, not far from the Port of Charleston, in 2018. Over 2,000 workers at the facility currently build high-end electric SUVs, and Volvo expects to contribute about $5 billion in annual economic activity. Overall, South Carolina's Chamber of Commerce reports 327 firms are currently active in the automotive industry; 143 of them operate under a company based overseas.

Why South Carolina?

Michelin executives in the 1970s were drawn to South Carolina for the available land, convenient access to ports like Charleston, and an available workforce in a state with the weakest labor union presence in the country. According to Joseph Von Nessen, an economist at the University of South Carolina, "Michelin arrived in South Carolina at a pivotal time. As textile manufacturing entered a long decline, Michelin sparked an evolution to advanced manufacturing in our state."

Those resource endowments and policies remain attractive to firms looking for access to both U.S. and overseas markets, especially those in the automotive sector. The Port of Charleston has been the state's door to the world, and the state has worked over the years to develop and expand inland connections to it from places like the Upstate. In an era when communities compete to attract domestic and international businesses, location and logistics mean the difference between success and failure. Communities that are not efficiently connected to the port either by railway or highway may lose out on the benefits that come with foreign investment.

Places positioned to benefit from those connections are likely to continue growing, attracting or generating additional resources that can, in turn, attract more firms to an area. This dynamic likely explains why so much advanced and auto manufacturing and related industries — some 2,450 firms — are concentrated in the Upstate. For example, in 2007, Clemson University founded the International Center for Automotive Research in Greenville, just off I-85. In addition to housing the university's automotive engineering graduate program, the campus is a hub for developing and testing emerging automotive technologies. The center has well-developed business relationships across the automotive sector, and 96 percent of its students find jobs with those firms after graduation. BMW also maintains its information technology research and development center on the campus.

In the 1990s, BMW was also attracted to South Carolina's workforce training system. Jennifer Moorefield is the associate vice president for corporate and continuing education at Greenville Technical College, and, during that time, she worked as a trainer, facilitator, and contractor with the college, helping to support local businesses with employee onboarding and retention. This collaboration between firms and the local technical college gave BMW the freedom to develop its workforce in its own way and bring workers into the BMW culture as it existed back in Germany. Since 2011, that relationship has been formalized through the BMW Scholars program, an apprenticeship program where students can attend class full time at one of four local technical colleges and work part time at BMW, gaining hands-on experience with the potential to become full-time employees. (See "Learning in the Fast Lane," Econ Focus, Fourth Quarter 2017.) Beyond BMW, the college currently has 187 apprenticeships active across 46 different companies.

Moorefield sees firms' relationships with the state's technical college system — originally developed as textiles declined in the 1960s and 1970s to train workers for the manufacturing jobs of the future — as a key element of South Carolina's manufacturing growth and success. For example, on its production line, Michelin employs a significant number of individuals for whom Spanish is their native language, and the company asked the college to develop a customized Spanish language curriculum so that plant supervisors could better communicate with their employees. "If you have a challenge, tell us what it is, and then we'll figure out the solution," says Moorefield.

Allen Smith is the president and CEO of OneSpartanburg, Spartanburg County's business, economic, and tourism development organization. He notes that the county is the 10th fastest-growing county in the United States, attracting about 10,600 new residents a year, a fact not lost on companies that are considering relocating to the area. Coupled with the fact that there are seven colleges in the county, he suggests that there's a workforce in place that can respond quite well to any industry needs. And firms, Smith argues, have been pleased with this arrangement. "Companies are coming here, and they're not one and done," Smith says. "Several years ago, Magna, the Canadian seat supplier, was announcing an expansion of their second facility before they had finished their first facility."

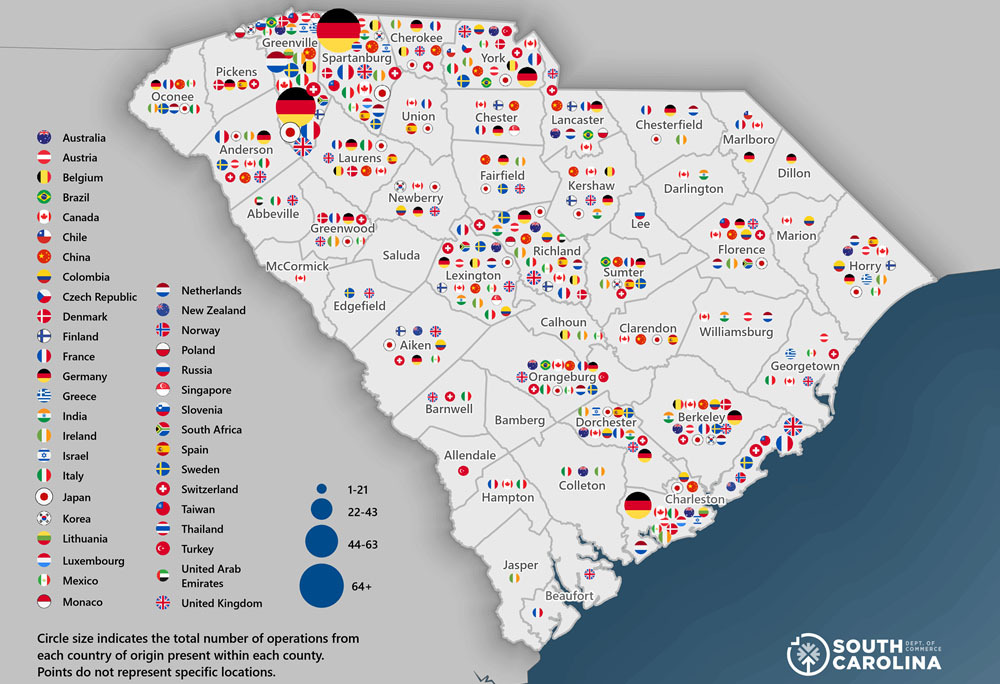

The state and local governments have also developed initiatives aimed at encouraging international firms of varying sizes to invest. (See map.) In 2016, for example, the South Carolina Department of Commerce established the Landing Pad program, which aims to help smaller international firms that plan to hire fewer than 10 employees and invest under $1 million as they settle into the United States.

Uncertainty Grows

In 2018, the United States imposed tariffs on Chinese goods. Those fees are typically collected at the goods' point of entry, but many firms were able to avoid paying by obtaining exemptions from the policy. Even still, the tariff changes proved disruptive.

"Lots of people did get exemptions," recalls Lummus, the CEO of the Upstate SC Alliance. "But it took time away from what businesses were trying to do because they were worried about getting an exemption rather than making a better product."

While current changes to tariffs are still being negotiated, researchers at the Richmond Fed led by economist Marina Azzimonti found that the average effective tariff rate could move from a benchmark of 2.3 percent to about 22 percent, second globally only to Bermuda. This scenario includes a 20 percent tariff on all Chinese imports, a 25 percent tariff on all auto imports except those exempt under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), a 25 percent tariff on all aluminum and steel imports, a 10 percent tariff on all Canadian potash and energy imports, and a 25 percent tariff on all non-USMCA exempt imports from Mexico and Canada. Due to its advanced manufacturing industrial base, South Carolina is particularly exposed to tariffs on aluminum and steel, as well as those on goods coming from China and Germany, the two countries with the largest number of imports entering through the Port of Charleston. According to Azzimonti's team, 10 counties in the state could see average effective tariff rates of at least 10 percent, and three could face rates of at least 14 percent.

South Carolina's auto manufacturers, BMW and Volvo, which combined exported $10.9 billion in automobiles in 2024 and together, along with Mercedes-Benz, support over 80,000 jobs, are very much aware of how a tariff policy raising prices on these supplies might impact their business, and they are trying to adjust. Both BMW and Volvo announced in early April they would increase production of cars for sale in the United States with the intention to localize production and potentially offset any declines in overseas sales due to retaliatory tariffs.

While these large firms might have the ability to bring online more production for domestic sales, where the tariff rates will end up remains a looming question. The government has imposed tariffs in recent months from as low as 10 percent to as high as 145 percent, and the numbers have changed frequently, creating significant challenges for firms trying to plan ahead.

Recent research suggests that uncertainty about tariffs can have meaningful adverse effects at both the macro and micro levels. A 2020 Journal of Monetary Economics paper by economists at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors showed that increased uncertainty reduces investment at the firm level and in the aggregate. A 2024 paper by Lukas Boer of the International Monetary Fund and Malte Rieth of Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg found similar results: Uncertainty depresses imports and investment, although output is less affected because exports rise as the exchange rate depreciates.

The first quarter 2025 CFO Survey, conducted by Duke University's Fuqua School of Business in partnership with the Richmond and Atlanta Feds, also indicated uncertainty regarding tariffs has dampened firms' optimism for growth, especially among those that source their inputs and supplies from Canada, China, and Mexico — the countries targeted under the initial round of U.S. tariffs. These firms were less optimistic about overall GDP growth and their own growth than firms not exposed to tariffs.

This uncertainty appears to be taking hold in South Carolina, as many tariff-exposed firms are pausing planned activities and investments. While trade volumes at the Port of Charleston were stable as of early June, planning has been difficult at the Port of Charleston. "We are on pause," noted Mary Beth Richardson, the port's director of financial planning, who says noncritical hiring and capital improvement projects have been placed on hold. "As an example, we were planning to buy two ship-to-shore cranes this year, and at this point pricing and sourcing are extremely difficult to predict," she says. "Thus, this project has been delayed for now until there is better clarity."

Volvo announced in early May it would be laying off about 125 workers at its Ridgeville facility due to tariffs. Small businesses are also trying to adapt. Many local businesses, from clothing retailers to outdoor suppliers, source much of their inventory from overseas because there are no domestic alternatives. Some small businesses have reported in local media that they have tried to get ahead of the tariffs, increasing their inventories before price increases kicked in. But after those are exhausted, they face an uncertain future.

Such a future contrasts with a vibrant, globally competitive present — in the auto industry and beyond — that has brought immense growth and pride to South Carolina. Allen Smith, the CEO of OneSpartanburg, maintains that free trade "has worked for us and continues to work for us."

Readings

Boer, Lukas, and Malte Rieth. "The Macroeconomic Consequences of Import Tariffs and Trade Policy Uncertainty." International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 2024/013, Jan. 19, 2024.

Caldara, Dario, Matteo Iacoviello, Patrick Molligo, Andrea Prestipino, and Andrea Raffo. "The Economic Effects of Trade Policy Uncertainty." Journal of Monetary Economics, January 2020, vol. 109, pp. 38-59.

Cole, David. "Revving the Economic Engine: South Carolina's Auto Cluster." National Association of Development Organizations Research Foundation, April 2013.

"Economic Impact Report." Autos Drive America and American International Automobile Dealers Association, 2024.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.