Supply Chain Resilience and the Effects of Economic Shocks

Key Takeaways

- Supply chains are key for transmitting shocks internationally. About half of a disruption's total effect may come from amplification through the supply chain network.

- The pandemic and its aftermath brought supply chain resilience policies to the forefront. About a quarter of GDP and inflation effects after 2020 are attributed to shocks outside the U.S. that propagated through the input-output network.

- Strategies to improve resilience are costly and might raise input prices. Firms are increasing input sources and inventory accumulation. Policies that re-shore production domestically or towards "friendlier" countries are also on the rise.

Supply chains have long been integral to the U.S. economy, allowing firms to capitalize on specialization and efficiency. However, recent developments like the COVID-19 pandemic, global geopolitical tensions and increasing climate risk have revealed their vulnerabilities as well as their abilities to propagate and amplify economic shocks. In response, firms and policymakers are increasingly focusing on strategies to bolster supply chain resilience. This article explores how economic shocks can propagate through the supply chain, the trade-offs associated with resilience investments, and policy responses aimed at strengthening the stability of U.S. supply chains.

Supply Chains Transmitting Shocks

Economic research has extensively analyzed how disruptions such as natural disasters cascade through supply chain networks, affecting not only firms but also their customers and suppliers. When a firm faces such a disaster, its immediate operations are disrupted, often due to physical damage that halts production temporarily.

However, the shock rarely stops there. Downstream firms — those that rely on inputs from the affected firm — experience indirect disruptions. Without access to critical supplies, these firms may face production delays or even a complete halt. Similarly, upstream firms — those supplying the disrupted firm — also feel the impact. With affected firms unable to purchase goods, suppliers face reduced sales until operations resume.

A 2016 study provides empirical insights into these dynamics, focusing on U.S. firms affected by natural disasters.1 Its findings highlight significant amplification effects: For every $1 sales the impacted firm loses, customer firms lose an average of $2.40 in sales. These effects were most pronounced when the disrupted firm produced differentiated or research-intensive goods (that is, inputs that are challenging to replace quickly).

A 2021 paper extended this analysis to the Great East Japan earthquake of 2011, tracing the shock's ripple effects across the supply chain.2 This paper found that half of the total economic impact stemmed from propagation to firms up to four degrees separated from those directly affected. These findings underscore how interconnected supply chains magnify localized disruptions, spreading their economic consequences far beyond the epicenter of the shock.

The Role of Supply Networks After the Pandemic

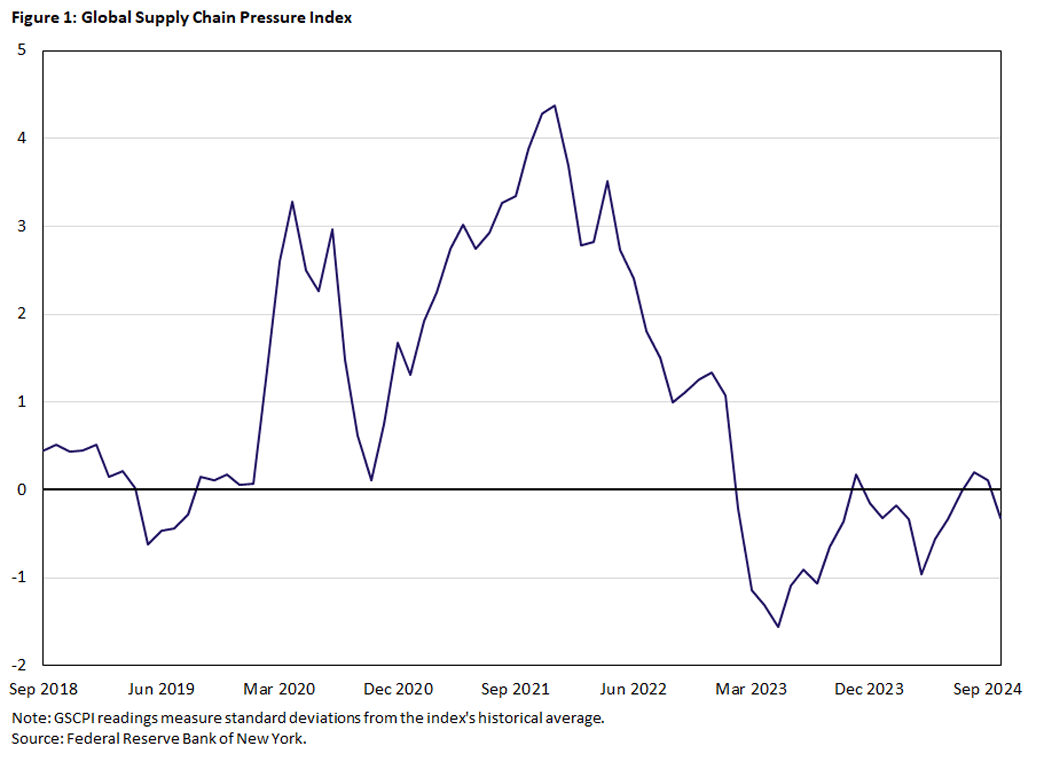

The COVID-19 pandemic reignited concerns about the vulnerabilities of globalization and the resilience of supply chains. In the U.S., economic shocks were magnified by disruptions in international supply chain linkages, emphasizing the interconnected nature of global trade. One tool for monitoring these dynamics is the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, developed by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. This index provides a composite measure of supply chain disruptions, capturing metrics such as shipping delays, order backlogs and inventory buildups.

As shown in Figure 1, supply chain pressures surged dramatically in early 2020 as global lockdowns halted production and disrupted logistics networks. By late 2020, as production resumed worldwide, pressures began to ease slightly but remained elevated. Supply chain bottlenecks then intensified again and peaked in December 2021, with this surge driven by rebounding demand and lingering disruptions in production and transportation. This pattern underscores the fragility of supply chains during periods of global economic upheaval and the challenges of adapting to sudden shifts in supply and demand.

The pandemic triggered significant disruptions to global supply chains, with international shocks affecting economic activity in the U.S. In early 2020, as lockdowns were implemented worldwide, production stalled, and goods delivery faced substantial delays. A 2021 paper quantifies the extent to which GDP declines at the onset of the pandemic stemmed from domestic versus international factors.3 The authors' analysis combines data on lockdown stringency with information on production and trade across countries and industries, revealing that about 30 percent of the U.S. GDP decline during the early pandemic was attributable to foreign lockdowns restricting imports. The remaining 70 percent was driven by domestic disruptions.

The researchers also examined whether international supply chains mitigated or amplified the economic impact of lockdowns in the U.S. While international trade could, in theory, buffer domestic lockdown effects by enabling imports from less-affected regions, this was not the case for the U.S. Lockdowns abroad were more severe than domestic ones, which ended up amplifying the negative impact on U.S. GDP. In contrast, countries with stringent lockdowns such as Peru and Argentina benefitted from international trade, mitigating their domestic shocks by importing goods from less-affected regions.

As global lockdowns eased in 2020, inflation surged worldwide, driven partly by a rebound in aggregate demand that strained production networks. A 2024 report analyzed the sources of inflation in the U.S. and found that international factors — such as supply chain bottlenecks and foreign demand — accounted for roughly 2 percentage points (pp) of the inflation observed in 2021 and 2022, about a quarter of the total inflation during that period.4 In Europe, where production depends more heavily on foreign inputs, international channels contributed up to 4 pp to inflation.

Firm-level dynamics also played a critical role in navigating supply chain disruptions. My 2022 working paper "Supply Chain Resilience: Evidence From Indian Firms" — co-authored with Gaurav Khanna and Nitya Pandalai-Nayar — examined characteristics of firms that proved resilient to COVID-19 lockdown shocks. Firms relying on highly differentiated inputs — products with fewer substitute suppliers — demonstrated greater resilience. These firms experienced fewer supplier separations, secured new suppliers more quickly and sustained production more effectively compared to firms sourcing more generic inputs. Interestingly, while such firms would have a greater amplification effect when receiving supply chain disruptions, their preparedness likely mitigated the broader economic consequences for the broader network.

Increasing Investments in Supply Chain Resilience

The pandemic highlighted the critical role of supply chains in the propagation and amplification of economic shocks. While the pandemic was an unexpected and temporary disruption, other shocks (such as climate disasters and geopolitical conflicts) are anticipated to occur more frequently and could lead to significant production disruptions if firms are unprepared. Policymakers and businesses are increasingly prioritizing investments in supply chain resilience to mitigate the effects of such shocks.

Firms are adopting a variety of strategies to enhance supply chain resilience. A 2022 survey of global supply chain leaders found that:

- About 81 percent of respondents planned to increase dual sourcing of raw materials.

- About 80 percent aimed to boost inventory holdings.

- About 44 percent sought to shift their sourcing strategies toward regional labor markets, often referred to as "re-shoring" production.

My 2024 working paper "Weathering the Storm: Supply Chains and Climate Risk" — also co-authored with Khanna and Pandalai-Nayar as well as Juanma Castro-Vincenzi — argues that firms are likely to source products from multiple suppliers to reduce risks, such as climate-related disasters affecting suppliers.

However, this approach entails a trade-off between efficiency and resilience. While regions with higher risks may offer lower production costs, disruptions in these areas can lead to costly supply chain interruptions. To mitigate these risks, firms are increasingly willing to pay a premium to source inputs from multiple, less-risky regions.

The trend toward regionalization is also evident in response to specific shocks. For example, my aforementioned 2022 working paper finds that, following the COVID-19 lockdowns and subsequent supply chain disruptions, firms became more likely to source inputs from geographically closer suppliers and larger firms. This shift reflects a broader effort to minimize vulnerabilities and ensure production continuity.

From a policy perspective, governments are supporting efforts to secure critical inputs through re-shoring and "friend-shoring" production. Geopolitical developments — such as the war in Ukraine and concerns over China's dominance in manufacturing — have prompted the U.S. and other nations to favor domestic production or trade relationships with "friendly" countries, such as Canada, Mexico and Vietnam. Policies such as the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 — which provides $52.7 billion to boost the U.S. semiconductor industry — exemplify these efforts. Similarly, tariffs introduced in 2018 (particularly those targeting China) remain in place and have shifted some market share away from Chinese imports. A 2023 working paper estimates that these tariffs reduced China's share of U.S. imports by 4 pp between 2017 and 2022, with Vietnam, Taiwan, India and Canada gaining market share among U.S. imports.5 However, the authors caution that this reallocation does not represent a complete shift away from reliance on China, as many of these new suppliers increased their dependence on Chinese inputs for intermediate goods during the same period.

Conclusion

The push for resilient supply chains reflects a trade-off between stability and cost. While resilience investments protect against future disruptions, they may raise input prices and inflation in the short term. Given the likelihood of increased climate events and geopolitical tensions, resilience is expected to remain a key priority for firms and policymakers alike. However, resilience-focused policies such as re-shoring, tariffs and incentives for domestic production may place upward pressure on costs, which could have lasting impacts on inflation and productivity.

Nicolas Morales is an economist in the Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

See the 2016 study "Input Specificity and the Propagation of Idiosyncratic Shocks in Production Networks" by Jean-Noel Barrot and Julien Sauvagnat.

See the 2021 study "Supply Chain Disruptions: Evidence From the Great East Japan Earthquake" by Vasco Carvalho, Makoto Nirei, Yukiko Saito and Alireza Tahbaz-Salehi.

See the 2021 study "Global Supply Chains in the Pandemic" by Barthelemy Bonadio, Zhen Huo, Andrei Levchenko and Nitya Pandalai-Nayar.

See the 2024 report "Pandemic-Era Inflation Drivers and Global Spillovers" by Julian di Giovanni, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Alvaro Silva and Muhammed Yildirim.

See the 2023 working paper "Global Supply Chains: The Looming "Great Reallocation'" by Laura Alfaro and Davin Chor.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Morales, Nicolas. (January 2025) "Supply Chain Resilience and the Effects of Economic Shocks." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-02.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.