Fighting Payments Fraud

From stolen checks to "deepfake" scams, fraudsters are costing businesses, banks, and individuals billions every year

For many people, TikTok has become their go-to source for information on everything from fashion to food to home maintenance. Gone are the days of having to figure it out yourself or "Google it"; influencers now post short videos detailing how to perform any number of supposed "life hacks" meant to make life a little easier or, at the very least, more entertaining. In the past year, one more hack joined the list: check fraud. The hack went viral in the fall of 2024, and it was surprisingly easy: Chase Bank customers wrote checks of significant amounts to themselves, deposited those checks into a Chase ATM, and immediately withdrew as much cash as possible even if they didn't have those funds in their accounts.

Chase's system allowed customers to make these unlimited withdrawals during the "float" period between when a check is deposited and when it is cleared. Whether or not everyone who exploited this supposed life hack knew it, they were engaging in what Chase described as "fraud, plain and simple." Chase was the victim in this case, and in response, it froze many of these accounts and is suing some of the biggest offenders to recoup the money it lost.

This case highlights a recent trend: Fraudsters are getting bolder, and losses are increasing dramatically. For example, consumers reported fraud losses of $12.5 billion to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in 2024, a 25 percent jump over the reported losses in 2023, which saw a 14 percent increase over losses in 2022.

Many victims do not file claims with the FTC, however. According to Devesh Raval, deputy director for consumer protection in the FTC's Bureau of Economics, the FTC's victimization studies have found only around 5 percent of fraud victims file a complaint, either with the FTC or the Better Business Bureau. "What we're seeing is the tip of the iceberg of fraud," he says. Additional reports by private fraud detection firms suggest that in 2023, check fraud amounted to $21 billion in losses, while $30 billion was lost to synthetic identify fraud. Overall, losses to different forms of fraud for that year alone were estimated to be $138 billion.

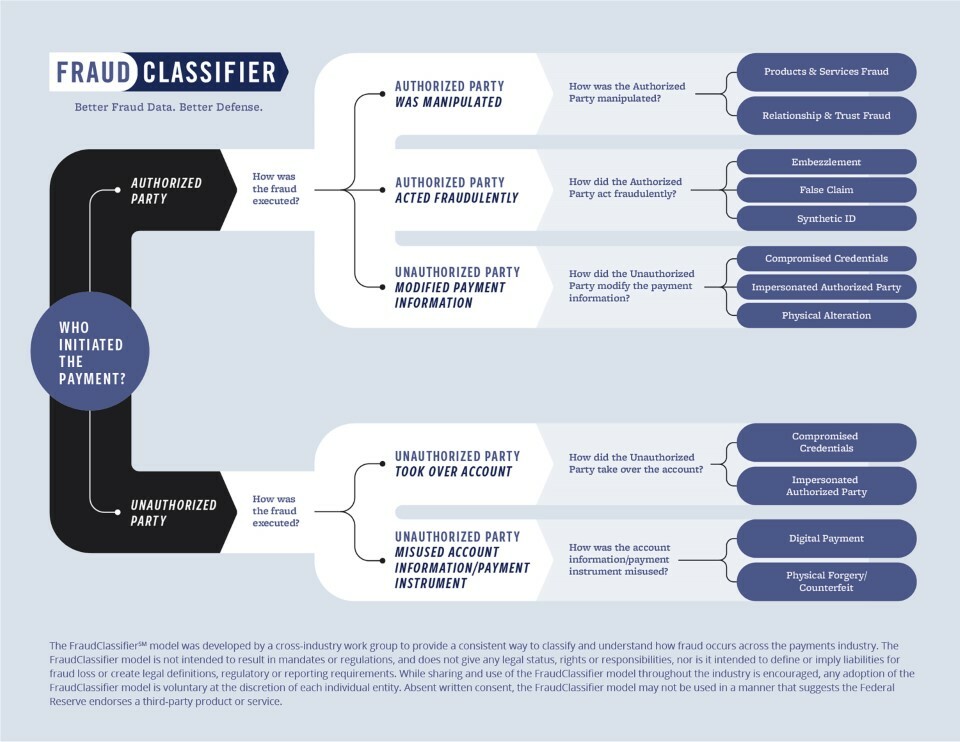

In 2020, to better track different and evolving kinds of fraud and how they are being used, the Federal Reserve released the FraudClassifier model, which allows for a common language across organizations dealing with fraud and facilitates internal consistency within organizations when evaluating different cases. (See figure). The model categorizes fraud based on how a transaction was conducted and whether it was authorized by the account holder. These categories give financial organizations the ability to identify trends in criminals' methods and respond accordingly, including educating their customers on how to better protect themselves.

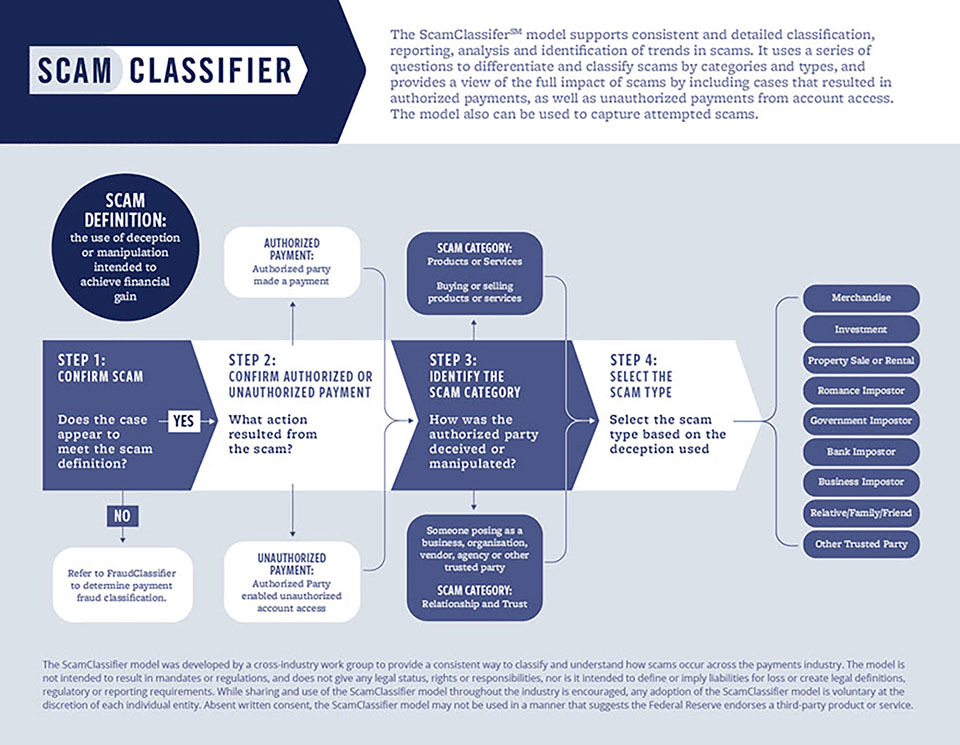

In 2024, the Federal Reserve debuted a companion ScamClassifier model specifically addressing scams, which constitute one of the largest categories of payments fraud, and which the Fed defines as "the use of illegal means to make or receive payments for personal gain." (See figure.) Victims of scams are deceived or manipulated into making payments or giving personally identifiable information (PII) to fraudulent actors posing as businesses, the government, or personal confidants. In cases where personal information is handed over, those fraudsters can make unauthorized payments or withdrawals from the victim's account.

Employing this broad spectrum of methods, fraudsters are engaged in a constant game of cat and mouse with bankers, regulators, policymakers, and law enforcement, who collectively are developing tools to block fraud, tracking down criminals, and educating the public to prevent people from falling prey to scams that can cause lasting financial harm.

Old School Tricks

While sharing methods for payments fraud on social media is a relatively recent phenomenon, checks have been a popular fraud target for over a century. In the 1920s, fraudsters would make a purchase by writing a check for a value greater than the balance in their account. Then, before that check cleared, they would write and deposit into that account another bad check from a second account at a different bank, with that check meant to cover the insufficient funds in the first account. Known as "check kiting," this would give the appearance of sufficient funds in the period before the two banks settle the transactions, known as the "float." Today, most transactions between banks are settled within one or two business days and banks limit how much can be withdrawn during the float, which makes check kiting more difficult to pull off successfully. But the similarities to the scheme shared on TikTok last fall show that this type of fraud has not been completely eliminated. (While it has not commented on how customers were able to withdraw seemingly unlimited funds, Chase has stated that "the issue has been addressed.")

Check use has significantly diminished in recent decades: The number of checks collected and processed annually by the Fed dropped by 82 percent over the past 30 years. But check fraud has more than doubled since 2020, according to the Treasury Department's investigative arm, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). While check kiting and the more recent TikTok schemes are authorized but fraudulent transactions conducted by the account holder, checks are also susceptible to unauthorized use by criminal actors. Paul Benda, the executive vice president for risk, fraud, and cybersecurity at the American Bankers Association, notes that checks are "an inherently insecure form of payment" for the simple reason that they contain an individual's name, address, bank account number, and bank routing number. That perhaps explains why they are in such demand by criminals, who will even steal them from the mail. Thieves have dropped glue-covered bottles tied to a string into the U.S. Postal Service's blue mailboxes to pull up whatever sticks — almost like fishing.

Staci Shatsoff, assistant vice president of secure payments at Federal Reserve Financial Services, says technology has enabled criminals in new ways. For example, the keys to those mailboxes have become "hot commodities" among criminals, who attack mail carriers and then copy the keys on 3D printers.

Once a check is in criminals' hands, they have gained access to the victim's account. They "wash" the check, removing the ink with something like nail polish remover, and then either write in new amounts for themselves or sell the clean checks, which can be copied and used repeatedly. "Checks are simple pieces of paper that can be totally recreated by buying check stock at Amazon or Staples," says Benda. "It's hard to fight." FinCEN received over 15,000 reports of mail theft fraud totaling more than $688 million in the six-month period between February and August 2023. That same year, the Association for Financial Professionals released a survey showing that check fraud was the top threat to business-to-business transactions, with 63 percent of respondents experiencing attempted or actual check fraud.

High-Tech Hijinks

Advances in technology have also unlocked new, more sophisticated methods of payments fraud. In April, cybersecurity software firm Imperva released a report noting that 37 percent of all web traffic in 2024 came from "bad bots." These small pieces of software are programmed to perform harmful tasks, such as gathering individuals' sensitive PII from banks and commercial websites or exploiting vulnerabilities in authentication processes to gain control of an individual's or business's account in what is known as account takeover fraud. The report found that banks are a top target for the bots, as about 40 percent were directed at the financial sector, and 12 percent of those were payment fraud bots sent to conduct account takeovers. Estimated global losses this year alone due to account takeover fraud are around $17 billion. Artificial intelligence (AI) has made tracking and combating these bots more difficult, enabling even criminals with no programming skills to create new, more harmful bots designed to avoid detection and successfully hack into secured systems.

In many cases, criminals use the bots to steal PII, not with the goal of account takeover, but to create entirely new synthetic identities. These combine the PII of several different people to come up with a new, fictional identity. For example, fraudsters may open a new account or line of credit using one individual's stolen Social Security number and birth date but someone else's name and address, making it harder to trace because it's very difficult to find a person who doesn't exist.

Shatsoff points out that the criminals creating these synthetic identities are patient. "They'll take these synthetic identities, open lines of credit, and act as if they're good customers," she notes. "They drive up their line of credit because they often make purchases in line with daily life and pay off those purchases every month, but once they get it to whatever amount they feel is comfortable, they max it out and then disappear."

That patience paid off for these fraudsters during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many of these synthetic identities established well before the pandemic created fake businesses and then applied for loans through the federal government's Paycheck Protection and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan programs, which were meant to help keep businesses afloat during the unprecedented upheaval. The Small Business Administration's (SBA) inspector general estimated that over $200 billion, or 17 percent of all disbursed funds, went to potentially fraudulent actors. Since the pandemic, however, the SBA, along with other federal agencies and financial institutions, has recovered nearly $30 billion of those funds.

Imposters!

While synthetic identity fraudsters create new individuals on paper, AI has enabled some criminals to more effectively assume the identities of real people. In early 2024, it was reported that an employee of a Hong Kong-based financial firm was tricked into sending $25 million to fraudsters who used "deepfake" technology to impersonate bank leadership on what the employee believed was an internal video call. The employee recognized the individuals appearing and speaking on the call, leaving no reason to doubt their authenticity. He only realized he had been scammed after following up with the firm's head office.

There have not been any reports of this happening to any financial institutions in the United States yet, but Benda of the American Bankers Association believes it is bound to happen. He notes that companies can purchase an avatar of their CEO, which can send congratulatory messages to employees without the CEO actually having to participate. "These avatars act and sound exactly like the person," he points out, "and we have seen scammers using real-time deepfake technology in romance scams, so it's only a matter of time before you see that in a more complex endeavor."

Imposter scams like these can take on a variety of forms, with fraudsters posing as business or government officials or establishing seemingly romantic relationships with potential targets. In these scams, targeted individuals are deceived into giving money or account details to someone they believe they can trust, when in reality they have been tricked, sometimes with devastating consequences.

"A Historical Perspective on Digital Currencies," Economic Brief No. 22-21, June 2022.

"The Growth of Paperless Money: Retail Payments in the United States Continue to Evolve," Economic Brief No. 09-06, June 2009.

Government imposter scams in particular are on the rise, as losses from these increased from about $618 million in 2023 to $788 million in 2024 — a nearly 28 percent jump in just one year. Raval of the FTC lays out how someone might be convinced to turn over their life savings to a fraudster posing as the commissioner of the FTC, for example. "First, someone calls you and says, 'We're Amazon, and there are unauthorized purchases on your account,'" he says. "And then Amazon says, 'We'll transfer you to the FTC,' and then someone claiming to be the commissioner tells the victim they need to move money out of their accounts to 'protect' it."

Developing the level of trust required to convince a stranger to turn over sensitive financial information can take a while. These longer-term scams are known as "pig butchering," as the victim ultimately meets a brutal fate when they realize their assets have been stolen. Many of these long-term schemes begin with a phone call made to a "wrong number," a connection on a dating app, or in the classic example, an email from a Nigerian prince. Over time, particularly in connections initiated on a dating app, the fraudster may bring up an investment opportunity and indicate they would be willing to manage the process if their target were to either transfer the money to them or provide their account details.

More recently, many of these investment scams have been focused on cryptocurrency, with Chainanalysis, a blockchain data analytics firm, estimating that crypto fraud scams amounted to over $12 billion in 2024. Nearly a third of those funds were lost through pig butchering scams, which grew over 40 percent from 2023.

Trying to Fight Back

Different forms of fraud require different responses from the parties impacted by the crimes. In the case of checks, many major banks are urging their customers to avoid mailing them and instead pay bills using cards, digital payment methods, or automated bill pay services.

"If you think of the nature of a check versus digital, there are just a lot more touch points where something can go wrong," says Shatsoff. She also notes that according to the Federal Reserve Payments study, although check use has fallen over time, the reported losses due to check fraud continue to increase year over year based on data from Nasdaq. (See "Speeding Up Payments," Econ Focus, Fourth Quarter 2017.)

In instances where individuals and businesses do have to write checks, banks have shared a list of best practices at practicesafechecks.com. They suggest using permanent gel pens, which have ink that is more difficult to remove. If the check is being sent in the mail, they suggest using mailboxes inside the post office rather than curbside or residential boxes. These steps are meant to protect both the account holder and the bank from criminals who sell stolen checks and instructions online for committing check fraud. Small businesses, for example, can be forced to shut down if one of these rings acquires its account information or is creating fraudulent checks from their account. In the cases of these unauthorized transactions, the banks will typically reimburse the victim, but the damage may have already been done.

More broadly, banks and organizations like the FTC and Federal Reserve engage in significant efforts to educate consumers about what fraud looks like in all its forms. For example, to combat bank fraud, where fraudsters pose as banks to collect consumers' PII or account details, the American Bankers Association developed the #BanksNeverAskThat campaign, reminding customers that banks will never ask for account PINs or passwords over the phone or personal details in text messages.

Individuals, however, still fall prey to these scams and the belief that they are giving money or account details to someone they trust. In these cases, where the transactions are authorized by the account holder, it is often much more challenging for the customer to be made whole.

Benda notes that in some cases where bank tellers suspect a customer who wants to transfer large amounts of cash to another individual is being scammed, they may require the customer to sign a statement that the bank believes they may be being defrauded. "It's a hard thing for a bank to be put in that position," he says. While banks cannot dictate how customers spend their money, the goal is to prevent the customer from engaging with criminals in the first place.

At the other end of these communications are people who themselves are often victims of fraud. Tricked by promises of a better life or trafficked, many people in Southeast Asia are lured to Myanmar and Cambodia and end up trapped in what amount to prison-like scam compounds run by international crime syndicates. There, they must sit in front of computer screens and run these scams using highly advanced and hard-to-combat AI technology to defraud their victims of a certain daily dollar amount or suffer physical abuse. Human rights advocacy organization Amnesty International identified 53 such farms in Cambodia alone, which generate between $12.5 billion to $19 billion annually, or 60 percent of the country's GDP.

The syndicates running these operations are difficult to stop, as their methods leverage evolving technologies that help them evade detection. Benda stresses that banks must have additional technological controls to stop them: "Can they identify an artificial voice? Can they look for mass password resets? Can they track the location of where a call comes from or where an account is being accessed?" Banks, of course, vary in their size and resources, and while some larger banks can build these controls internally, smaller community banks must rely on external service providers and off-the-shelf solutions.

In the meantime, the Fed continues to educate the public, businesses, and financial institutions about the dangers and methods of scammers. It and other federal bank regulatory agencies (the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) announced a formal request for information in June on potential actions to help consumers, businesses, and financial institutions mitigate risk of payments fraud, with a particular focus on check fraud. The comment period will remain open until Sept. 18.

"How can we better look at fraud and have a more strategic approach? It's hard to make an impact if everybody's just working in their silos," says Shatsoff.

Readings

Crosman, Penny. "Bad Bots are Taking over the Web. Banks are Their Top Target." American Banker, April 21, 2025.

"Financial Trend Analysis." Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 2024.

Timoney, Mike. "Why is Check Fraud Suddenly Rampant?" Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Aug. 23, 2023.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.