How Exclusive Homebuyer Representation Contracts Help Keep Commissions High

Key Takeaways

- Real estate agents use exclusive buyer representation contracts to capture homebuyers and thus limit outside options of home sellers.

- With outside options severely limited, home sellers pay high commissions (up to 6 percent) to sell their homes on the platform of real estate agents.

- A ban on exclusive buyer representation contracts is strongly pro-competitive: It improves the sellers' outside options and forces the platform to reduce real estate commissions to constrained-efficient levels.

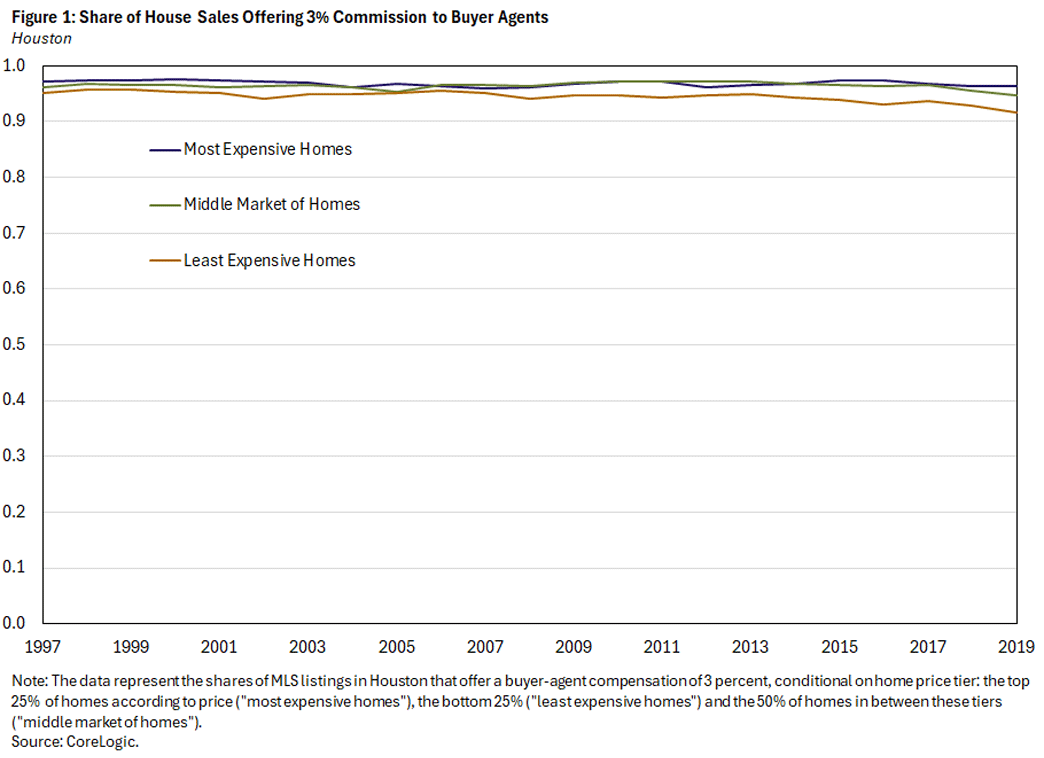

That real estate commissions in the U.S. are high (compared to the rest of the world) and rigid has been well-documented.1 Figure 1 uses Houston as an example and shows that 96.5 percent of all for-sale home listings in the area offered exactly 3 percent of a home's final sale price as commission to the buyer's agent. With an equal commission for the seller's agent — which is the industry's standard practice — sellers paid 6 percent of their home's value in real estate commissions in nearly all home sale transactions in Houston between 1997 and 2019.

Commissions Exceeding the Cost of Service?

Figure 1 strongly suggests that real estate commissions are not determined by the agents' costs of service. First, the 3 percent buyer-agent commission prevails among low-priced, medium-priced and high-priced homes alike. Second, home prices in the U.S. went through a few boom-bust cycles over the sample period. Third, we have seen tremendous advancements in information technology over that period. Yet, none of these changes affected commissions rates, suggesting that commissions are not set to match the cost of service. They must, therefore, be consistently higher than the cost of service.

Other metro areas in the U.S. are similar to Houston. Using a national sample of 77 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), we show in a recent working paper on real estate broker commissions that there is no systematic relationship within a metro area between the home's price and the commission rate. Across metro areas, we do observe a small degree of variation.

These observations raise several questions:

- Why doesn't competition among agents force commissions down to the level of the agents' cost of service? With relatively free entry into real estate brokerage, new entrants should be able to undercut the prevailing commission rate a bit, win a big chunk of the market and make a lot of money.

- Why doesn't competition from alternative trading venues outside the network of real estate agents altogether force commission rates down to cost-of-service levels.

- If the cost of service doesn't determine commission rates, then what determines them in metro areas across the country? For example, why is it 6 percent in Houston and not 8 percent?

The first question has attracted a fair amount of attention and research in the literature: As agents work with one another over long periods of time — repeatedly matching sellers with buyers — collusive pricing can be self-enforcing, even if entry of new agents is relatively unobstructed.2 In our recent working paper, we turn our attention to the latter two questions.

Exclusive Representation Contracts Are a Foundation for Monopoly Power

Exclusive representation means the agent representing a seller (or a buyer) receives a commission if a home is sold (or bought), regardless of how the counterparty to the trade was found. In our paper, we find that two-sided exclusive representation agreements used by the platform of real estate agents (reinforced by network externalities3) reduce sellers' bargaining power. They also help limit competition from potential alternative platforms on which real estate could be sold.

Seller agents generally require exclusive rights if they are going to market the home beyond just listing it on the multiple listing service (MLS) platform. They also typically require sellers to make upfront offers of compensation to buyers' agents. If sellers do not offer the compensation rate that "every other seller offers," buyer agents may steer clients away from these properties.4 This threat greatly diminishes sellers' bargaining power. If everyone offers 3 percent to buyer agents, no seller wants to stand out by offering 2 percent or 1 percent. Similarly, a seller's option to sell through other means is rendered impractical if most buyers are signed to exclusive buyer representation contracts. Exclusive attachment of buyers to the platform, thus, staves off competition from outside trading venues.

How does the platform manage to sign buyers into exclusive representation contracts? It is a combination of a carrot and a stick, reinforced by the network effects of the two-sided platform.

The buyer-agent representation contract consists of two key clauses. The first clause is the stick: The buyer promises to pay the buyer-agent commission (usually 3 percent) regardless of how the buyer finds the home. That is, even if the buyer agent ultimately didn't help the buyer find the home they wish to purchase — for example, the buyer finding the home through an open house event — the buyer is still required to pay the commission.

The second clause is a carrot: If the buyer stays on the platform — where sellers already offer compensation to buyer agents — that compensation will be counted against the commission due from the buyer. Thus, if the buyer's obligation matches the seller's offer (which is commonly done at 3 percent), the services of the buyer's agent are "free" to the buyer as long as the buyer stays on the platform, as the seller pays the buyer agent's commission.5

Such a contract effectively presents a binary choice to the buyer: search exclusively on the platform or exclusively off it. Faced with this choice, buyers essentially have to sign with and stay exclusively on the platform. The network effect reinforces this decision: Since sellers anticipate buyers being on the platform, they likely list on only the platform. Given this expectation, it is not optimal for an individual buyer to give up on the MLS platform and search away from it, where there are no listings, especially so with buyer-agent services provided on the platform "for free."

The same network effect effectively eliminates the sellers' option to sell off the platform. Since sellers anticipate buyers to be tied exclusively to the platform, trying to sell their homes off the platform is not practical because the buyers are not there. This network externality creates market power for the platform making it a de facto monopoly vis a vis the sellers: Real estate agents and their MLS platform provide the only practical option for selling everywhere in the U.S.

Absentee Homeownership Option Limits Platform Profit

This brings us to the third big question: Why should the platform stop at 6 percent? Why not charge 8 percent, for example? In our working paper, we point to another outside option that sellers have: not selling.

People put their homes on the market when they become mismatched with their home — due to, for example, a job or family change — and, thus, need to move. However, moving but holding on to the house instead — that is, becoming a so-called absentee homeowner — remains a possibility. This option puts an upper bound on the commission the platform can charge.

Absentee homeownership entails costs that owner-occupants do not face, such as:

- Rent risk

- The cost of searching for renters

- Property management fees

- Taxes on rental income

- Increased upkeep costs due to the homeowner not being present on the premises

The commission to sell a home can be at most as high as the present discounted value of these costs. In fact, under a weak assumption on the distribution of private mismatch shocks that turn homeowners into potential home sellers, it is optimal for the platform to charge a commission fee exactly as high as the absentee homeowning costs.

In our working paper, we verify this prediction of our model in the data. We find that MSAs where rents are higher relative to home prices indeed have lower average commission rates. Higher rents mean absentee homeownership costs are lower, and, thus, the monopolist real estate platform cannot charge as much.

Banning Exclusive Buyer Representation Contracts Restores Competition

What then can be done to increase competition in residential real estate? In our working paper, we show that a ban on exclusive buyer representation contracts is strongly pro-competitive. Such a ban unlocks sellers' options to sell their homes off the platform.

With exclusive buyer representation contracts banned, buyers are not faced with the binary choice of searching either on or off the platform, as they can search both ways. Since buyers may now find houses away from the platform, sellers' bargaining position vis a vis the platform improves. As a result, the platform's charge would be lower than the 6 percent we observe in Houston (and elsewhere).

This equilibrium rate is in fact constrained-efficient: The platform still earns positive profits but only if it really provides seller-buyer matching outcomes superior to what's provided on the open market (that is, off the platform). Also, the constrained-efficient equilibrium rate is not the same in all home-value segments: Larger, more valuable homes pay a lower rate. And it is not insensitive to IT improvements and associated reductions in the underlying search frictions: Decreased search costs imply lower commission rates across the board in the constrained-efficient equilibrium.

Further, we find that the number of agents working in the industry goes down, which eliminates excessive entry of agents and the problem of wasteful nonprice competition among them.6 As a result, the average agent remaining in the industry should serve more clients, thus earning less per client but not less per year.

In sum, our recent working paper explains how the association of real estate agents can position itself as a de facto monopolist for residential secondary-market real estate transactions in the U.S. We show that exclusive buyer representation contracts are a key element of this positioning. A ban on such contracts is strongly pro-competitive. It results in lower commission rates, lower (but still positive) platform profits and fewer agents serving more clients and earning the same compensation without the need to waste resources chasing leads and competing for monopoly-platform rents.

Borys Grochulski is a senior economist and Zhu Wang is vice president for research in financial and payments systems, both in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

For example, see the 2003 paper "Can Free Entry Be Inefficient? Fixed Commissions and Social Waste in the Real Estate Industry" by Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti; the 2017 paper "Conflicts of Interest and Steering in Residential Brokerage" by Panle Jia Barwick, Parag Pathak and Maisy Wong; and the 2025 paper "Et Tu, Agent? Commission-Based Steering in Residential Real Estate" by Jordan Barry, Will Fried and John William Hatfield.

For example, see the 2025 paper "Collusion in Brokered Markets" by John William Hatfield, Scott Duke Kominers and Richard Lowery.

By network externality, we mean that a seller's value from listing the home with the network of real estate agents depends on how many buyers are signed with and searching through that network, but this is something the buyers themselves do not internalize. Vice versa, a buyer's value from signing with an agent depends on how many sellers list, but sellers do not internalize that either.

The previously cited papers "Conflicts of Interest and Steering in Residential Brokerage" and "Et Tu, Agent? Commission-Based Steering in Residential Real Estate," as well as the 2024 working paper "The Equilibrium Impacts of Broker Incentives in the Real Estate Market (PDF)" by Gi Heung Kim show evidence of such steering by buyer agents.

In practice, buyers may pay commissions indirectly through higher home prices, which likely factor in the commissions paid by sellers, at least partially. See the 2024 working paper "NAR Settlement, House Prices and Consumer Welfare" by Greg Buchak, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski and Amit Seru, as well as our 2024 working paper "Real Estate Commissions and Homebuying."

The problem of excessive agent entry and competition for platform rents is explained and documented in the previously cited paper "Can Free Entry Be Inefficient? Fixed Commissions and Social Waste in the Real Estate Industry."

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Grochulski, Borys; and Wang, Zhu. (September 2025) "How Exclusive Homebuyer Representation Contracts Help Keep Commissions High." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-35.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.