These posts examine local, regional and national data that matter to the Fifth District economy and our communities.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Fifth District Economy

Introduction

As the COVID-19 pandemic spreads across the country, Americans are taking measures to distance themselves from their communities, both voluntarily and by mandate. This is no different in the Fifth Federal Reserve District, which includes the District of Columbia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and almost all of West Virginia. Starting March 24, the governor of West Virginia issued an order for citizens to stay at home except in extremely limited circumstances. Starting March 30, the governors of Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia, and the mayor of the District of Columbia issued orders for citizens of their jurisdictions to stay at home except for essential trips, such as grocery shopping or medical appointments. As of April 1, the governor of South Carolina ordered all nonessential businesses closed and banned public gatherings of more than two people. These measures are, of course, taking a toll on our District economy. This Regional Matters post will discuss both the measures that have been taken in our District to support social distancing and the industry structure of our District in an attempt to better understand the economic impact of COVID-19 on the Fifth District.

What Has Happened?

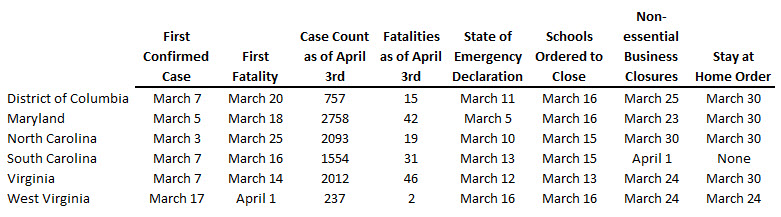

As of April 3, 2020, 9,411 people across the Fifth District were diagnosed with COVID-19. Table 1 provides information on the first confirmed case, the number of cases and fatalities as of April 3, and the social distancing measures that have been taken in the Fifth District. By March 16, schools were closed across states and nonessential businesses are closed in every state as of April 1.

Due to the lagged nature of economic data, the best information we have to gauge the impact of the social distancing measures on economic activity is unemployment claims, which skyrocketed in the U.S. and in the Fifth District in the last two weeks of March. During the week that ended on March 28, around 6.6 million unemployment claims were filed in the U.S. and 462,411 were filed in the Fifth District. These numbers dwarfed any previous high, including the 2008-09 recession, as is evidenced in the chart below. On April 3, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released the national employment situation (the state data will be released on April 17), which showed a loss of 701,000 jobs in March and an unemployment rate of 4.4 percent. About two-thirds of the job decline was in the leisure and hospitality industry. Of course, most of these data, particularly the unemployment rate, were based on information from the middle of March. Thus, the April report for both the U.S. and the states will tell a much different—and more dire—story.

What Is the Makeup of the Fifth District economy?

The Department of Labor does not release the distribution of unemployment claims by industry on a weekly basis. However, in their April 2 press release, they wrote that "states continued to identify increases related to the services industry broadly, again led by accommodation and food services…however, many states continued to cite the health care and social assistance, and manufacturing industries, while an increasing number of states identified the retail and wholesale trade and construction industries." The facets of this pandemic will impact industries differently.

First, the social distancing measures impose restrictions that will severely impact businesses like hotels, air transportation, and restaurants. Second, there will be a broader decline in consumer demand that will result from increased unemployment, losses in wealth from the stock market declines, or uncertainty in the economy. Third, there are effects from the virus itself: For example, if a person tests positive in a manufacturing plant, the whole plant could shut down for a period of time. And finally, there are related effects such as low commodity prices (e.g., energy prices) that will negatively impact activity in the mining and extractive industries.

The first effect will impact the leisure and hospitality sector most severely. Sources such as STR and OpenTable report unprecedented declines in bookings at hotels and restaurants, respectively. The third and fourth effects will be more targeted, and in the case of a closure, hopefully more limited in time. It is the second effect of decreased consumer demand that threatens to creep across industries. As consumers and businesses become less certain about the future, they will spend and invest less, which could impact industries that range from auto manufacturing to administrative services.

Over time, the Fifth District (like the U.S.) has become more service oriented. As is clear in the chart below, employment in manufacturing has given way to increases in professional and business services and education and health services. The leisure and hospitality sector grew over the 30 years from 8.1 percent of employment to 10.8 percent of employment. Of course, this can vary by state, as is clear from the chart farther below titled Distribution of Employment in Select Industries by State.

Nonetheless, if we think about the effects of COVID-19, there is little about the structure of the Fifth District economy to indicate that we will be affected differently than the U.S. as a whole. The chart below shows a similar distribution of employment across industries. (Note, of course, that this is not taking into account the spread of the virus; we are only considering the negative effects of social distancing measures or lower consumer demand on activity.)

A More Detailed View of the Fifth District Economy

Using a more granular source of data, the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), enables a more detailed look into industries within states. We use 2018 data from the QCEW because it is the last full year of data available.

In the Fifth District, we have roughly 1.6 million people who work in food services, accommodation, arts, entertainment, or recreation—all of whom will be affected by social distancing measures. There are an additional 1.3 million who work in non-food retail who are also likely to be affected. (See chart below for a breakdown by state.) In total, these industries account for about 24.4 percent of the 15 million people who work in the District, so the impact could be sizeable. In the U.S, those industries account for 23.2 percent of employment. Again, although the impact could (and probably will) differ by state, there is nothing in the distribution of employment in the District as a whole to indicate that the economic impact of the social distancing measures will be notably different from that in the U.S.

Of course, all workers will not be equally affected. Lower-wage workers—many of whom work in the service industries identified above—generally have substantially less income, and thus savings, built up to weather the reduction in hours worked. The fiscal stimulus package should help, but the longer this goes on, the more likely it is that those workers will suffer. And the longer this goes on, the stronger and more persistent the effect on consumer demand will be.

In Summary

The extent of the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic in the Fifth District is unknown, but the near-term impact is sharply negative. Initial unemployment claims have skyrocketed, and businesses such as hotels and restaurants have seen revenues and bookings go to zero — in the U.S. and in the Fifth District. There is no reason to think that the Fifth District as a region will be harder hit than the nation as a whole, but just how persistent the economic impact will be depends considerably on how long the social distancing measures last. The fiscal stimulus package will help, as will policies undertaken by the Federal Reserve. However, as Thomas Lubik and Sonya Waddell wrote in their recent paper, in order to quickly return to pre-pandemic levels of economic activity, "workers need something to return to… so the businesses that employed them need to reopen or stay open." The longer this lasts, the harder that will be — in the nation and in our District.

Have a question or comment about this article? We'd love to hear from you!

Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.