A Tale of Three Cities: Richmond, Charlotte, and Baltimore

In 2016, over 90 percent of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) was attributable to metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs, while they occupied just under 50 percent of the nation's land mass. The economic importance of urban areas in the Fifth District is no different. In 2015, over 75 percent of the Fifth District population lived in metro areas that generated over 90 percent of economic output. Meanwhile, Baltimore, Charlotte, and Richmond alone not only house the three branches of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, but they account for over 20 percent of the Fifth District's population and close to a quarter of its GDP.

Of course, when most people think of an urban area, the first thing that comes to mind is a city like New York, Tokyo, or San Francisco—tall buildings, high population density, and crowded public transportation. Others may think of cities such as Richmond or Baltimore: slightly less dense, fewer high-rise buildings, but still with small plots for houses, sidewalks for walking, and cars crowding at traffic lights. However, some metro-area counties, often on the outskirts of a metro area, can be much less dense than the urban core of the metro area.

The distinction between central cities and metro areas is important in social and economic outcomes as well. The unemployment rate for the Richmond MSA was 4.1 percent in 2016 compared to 4.6 percent for the city of Richmond. The numbers in Baltimore are even starker: The unemployment rate in the city was 6.3 percent in 2016 compared to 4.4 percent in the metro area. In Baltimore city, almost 24 percent of people live below the poverty rate compared to about 11 percent in the broader metro area.

Why Do Cities Exist?

Cities arise because there are advantages to concentrating economic activity in one place, what economists call agglomeration economies. When businesses in the same industry cluster, they can benefit, for example, from sharing inputs, such as intermediate manufactured goods or skilled labor.

Firms can also benefit from the knowledge spillover that occurs from more people living and working in close proximity; in other words, new ideas spread more easily with a concentration of people and businesses. In this way, economic development can beget economic development. For example, one of the most compelling arguments for locating a Federal Reserve Bank in Richmond in 1914 was to take advantage of its existing transportation and banking infrastructure.

In Baltimore, the city first benefited from the port and then from the railroad built in the mid-19th century and the telegraph line that soon accompanied the railroad. The advent of steam power enabled new industries to be built closer to the harbor. By the 1880s, Baltimore had become America's leader in canned fruits and vegetables and a major producer of fertilizer. It also became a leader in manufacturing chrome, copper, and, most importantly, steel.

From railroads, bridges, and equipment to automobiles and tin cans, the steel industry grew considerably through the early 20th century, and Baltimore grew along with it. But the subsequent decline of manufacturing in the city of Baltimore has created challenges for residents and city officials alike. The city's population peaked at 950,000 residents in 1950. By 1995, only 8 percent of the city's jobs were in manufacturing.

Richmond's development also relied on agglomeration economies, particularly surrounding the tobacco industry, iron foundries, and flour mills. By the 1840s, Richmond had become the largest tobacco production market in the world. There was other manufacturing, too: paper and paper products, iron, and steel among them. The population outside of Richmond's central city grew by 24.3 percent in the 1960s.

The evolution of Charlotte is a little different in that it was never a stronghold of manufacturing activity and it is not on a major body of water and therefore could not rely on port activity. The growing of cotton in the South did engender cotton and textile mill activity in Charlotte, and by the early 1900s about 300 mills had been built within 100 miles of the city. The cotton, combined with J.P. Morgan's Southern Railway, contributed to Charlotte's growth.

Nonetheless, the city's population was still dwarfed by those of Baltimore and Richmond: The population of Charlotte reached 82,000 by 1930. Although manufacturing continues to be an important part of the Charlotte economy, transportation (such as railways in the early days and later the hub airport) and banking that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s drove continued growth in the Charlotte region. Unlike Baltimore, instead of losing residents in the last 60 years, the city of Charlotte has grown along with its surrounding counties. (See chart below.)

The Central Business District

As firms cluster, they create an area of concentrated economic activity, often referred to as an urban core or a central business district (CBD). For households, although commuting costs are lower close to work, housing is more expensive, so people might choose to live farther away to get more land. (Of course, house prices will also reflect features such as the quality of schools, access to parks, and crime rates.)

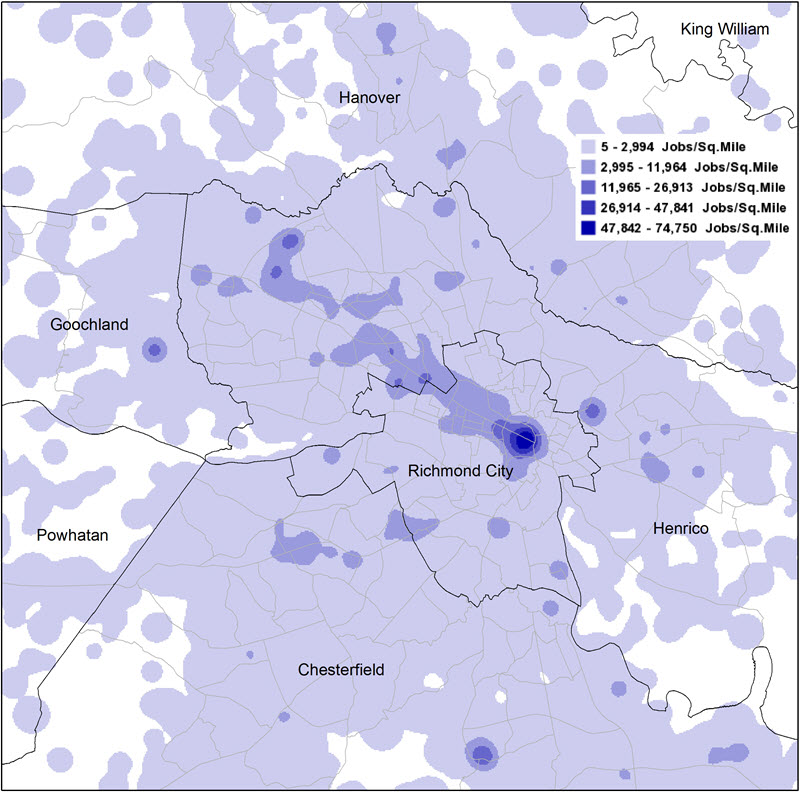

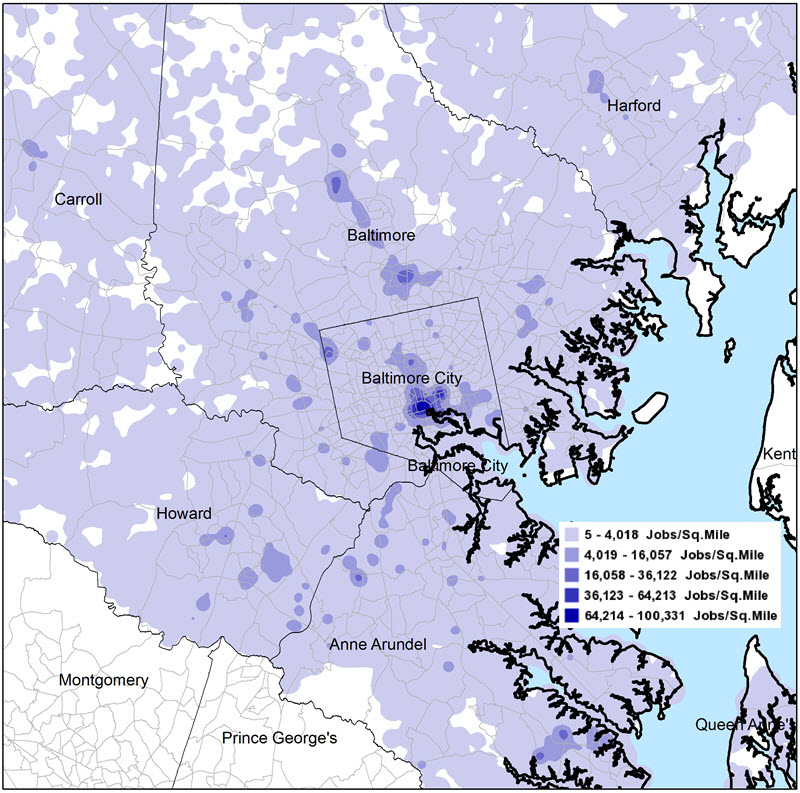

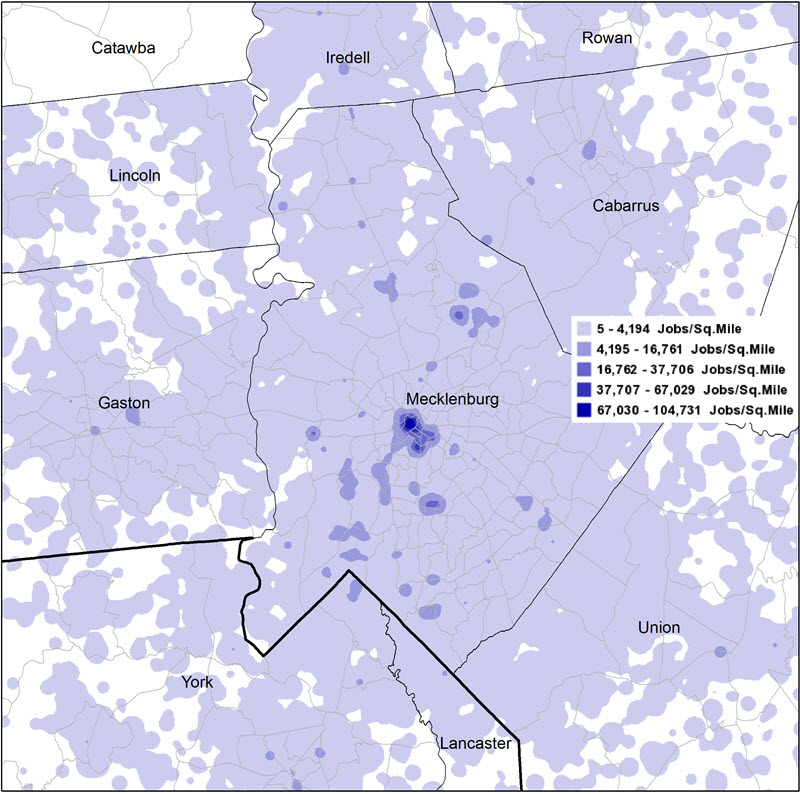

In his basic urban land model laid out in his 1964 book Location and Land Use — which has been a basis for much of urban economics — William Alonso modeled a city with a single center where the CBD is home to all of the jobs and the space surrounding the CBD is used for residential purposes. Of course, this is overly simplified: Job density across Richmond, Baltimore, and Charlotte (as in most cities) reflects that these areas have multiple urban cores. (See maps below.)

In Richmond, for example, there is a concentration of jobs in the downtown area, but also in the western and southern part of the region. To build upon the single-center model, economists have used both traditional methods to model multiple employment centers and some new empirical methods that have been enabled by developments in the trade literature as well as the increasing granularity of available data.

In most U.S. cities, wealthier households tend to live farther away from the city center (with some notable exceptions), perhaps because wealthier households prefer to occupy more land — although as the household continues to gain wealth, it might move back to avoid spending time commuting. That's why both very poor people and very rich people are often concentrated in city centers. Although over 52 percent of those who work in the city of Baltimore make over $3,333 per month, only 37.6 percent of people who live in the city make more than $3,333 per month. In Richmond, 48.3 percent of those who work in the city make more than $3,333 per month although only 35.2 percent of those who live in the city make that level of wage.

Of course, there are both benefits to city living (concentrations of people make amenities such as restaurants and theaters commercially viable) and costs. It is the costs that prevent cities from growing without limits. For example, higher density brings congestion and a higher cost of land.

Conclusion

Richmond, Baltimore, and Charlotte are extremely different cities. They each developed because of a combination of their natural endowments, specific policy goals of local officials, and some catalyst that engendered growth in a particular industry at least in part through agglomeration economies. Richmond benefited from its location close to the James River and the tobacco industry; Baltimore relied on its harbor and the steel industry; and in Charlotte, the political and business leadership brought textile mills, hubs of transportation, and, in the 1980s and 1990s, banking.

As cities like Baltimore and Detroit grapple with how to address an aging housing stock and diminished population, researchers wonder if targeted and thoughtful investments could provide a catalyst for the reinforcing mechanism of agglomeration economies — policies where the benefits might outweigh the costs. Recent work has brought to light a new opportunities to realistically model cities in order to better understand the effects of a shock to a city's economy or the likely effects of new policies.

(Note: This report contains excerpts from a recent Econ Focus article. For the full text and additional charts, see here.)

Have a question or comment about this article? We'd love to hear from you!

Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.