The Urban Core in the Tale of Three Cities

The Fifth District economy — like the U.S. economy — is increasingly driven by urban areas. In 2016, over 90 percent of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) was attributable to metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs, while they occupied just under 50 percent of the nation's land mass. This is not a new phenomenon, but it remains an important one. There is a long history of literature that aims to understand how and why cities develop and the opportunities and constraints faced by firms and households in that development. In addition, the contraction of certain cities in the past few decades (such as Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh) has puzzled economists and spurred interest in better understanding how and why cities contract.

The economic importance of urban areas in the Fifth District is no different from that in the United States as a whole. In 2015, over 75 percent of the Fifth District population lived in metro areas that generated over 90 percent of economic output. This article will start to disentangle the economic literature on the existence, growth, and decline of cities in the context of three very different cities in the Fifth District: Baltimore, Md., Charlotte, N.C., and Richmond, Va. In addition to being home to the three physical branches of the Richmond Fed, these three metro areas account for over 20 percent of the Fifth District's population and close to a quarter of its GDP. And although these three urban areas cannot compete with the economic power of Washington, D.C., in the Fifth District, they are arguably more typical in the forces that affect their economic trajectories; perhaps the differences and similarities among them can cast some light on the forces that affect cities in general.

What does "Urban" Mean?

When most people think of an urban area, the first thing that comes to mind is a city like New York, Tokyo, or San Francisco — tall buildings, high population density, and crowded public transportation. Others may think of cities such as Richmond or Baltimore: slightly less dense, fewer high-rise buildings, but still with small plots for houses, sidewalks for walking, and cars crowding at traffic lights. Those images are of urban cores, but very often, the available data that we have to describe urban areas are at the level of the MSA, which is often a much larger territory than the urban area. (See "Location, Location, Location: The economic differences between rural and metro areas in the Fifth District," Region Focus, Fall 2009.)

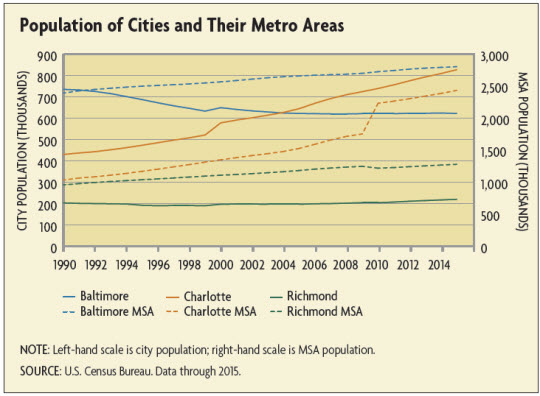

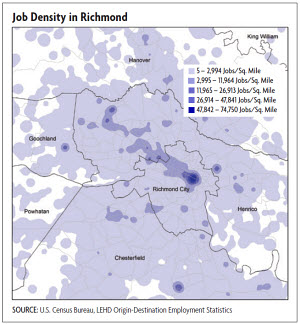

Compared to an MSA as a whole, the urban core of an MSA better fits our vision of a city: Louisa County, for example, which is part of the Richmond metro area, has a population density of about 67 people and 33 housing units per square mile compared to almost 3,500 people (and over 1,600 housing units) per square mile in the city of Richmond (and compared to almost 70,000 people and over 37,000 housing units per square mile on Manhattan). The distinction between central cities and metro areas is important in social and economic outcomes as well. The Richmond MSA, for example, has a little under 1.3 million residents while the city of Richmond has about 225,000 residents. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate for the MSA as a whole was 4.1 percent in 2016 compared to 4.6 percent for the city of Richmond. The numbers in Baltimore are even starker: The unemployment rate in the city was 6.3 percent in 2016 compared to 4.4 percent in the metro area. In Baltimore City, almost 24 percent of people live below the poverty rate compared to about 11 percent in the broader metro area.

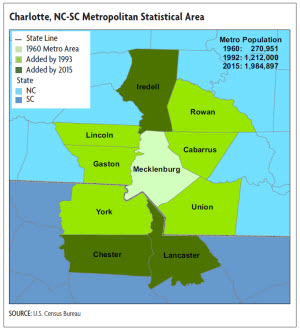

The physical footprints of most metro areas have expanded over time. The growth of the Charlotte MSA from 1960 to today — it is now multiple times its initial size — exemplifies this expansion. (See map below.) The concept of a metro area is based on a large population nucleus with surrounding communities that have a high degree of social and economic integration with that nucleus. For a county to be a part of an MSA, at least 25 percent of the workers living in that county have to work in the central county (or counties) of the metro area, or at least 25 percent of the employment in that county must be accounted for by workers who reside in the central county — like a reverse commute. (There are urbanization/population requirements to be considered a central county or counties.) Therefore, the growth of metro areas is not just about population growth or rising density of economic activity in the expanding periphery; it is also about how many people commute to an urban core. Commuting patterns and availability of transportation then become critical to understanding changes in urban areas.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.