The island's territory status also has implications for its economy. For example, the island is subject to U.S. minimum wage laws, but the U.S. minimum wage is higher than the real market wage for Puerto Rico's largely unskilled labor force. In a June 2015 report, economists Anne Krueger, Ranjit Teja, and Andrew Wolfe argued that is one reason — though not the only one — that 60 percent of its population is either not working or in the "grey economy" (compared to roughly a third on the mainland). A weak labor market has depressed growth and fed migration to the U.S. mainland, since Puerto Ricans can migrate freely, with a population decline of about 1 percent annually for the last decade. Also, the Jones Act, which requires that all shipping between U.S. ports use only U.S. vessels and crew, raises the cost of trade with the mainland. Economists disagree on the extent to which these factors have contributed to the longer-run fiscal problems, thus affecting Puerto Rico's ability to service its debts, but they continue to be a source of heated debate.

Puerto Rico was able to make its scheduled debt payment in December but defaulted on part of another in January. Garcia Padilla warned that the payments it did make were made at the expense of future payments.

The Bankruptcy Question

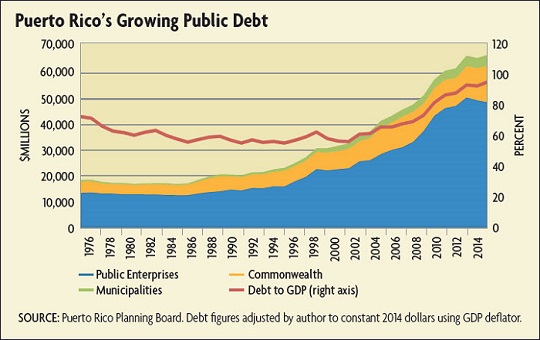

The island's estimated shortfall is $28 billion over the next five years. Fiscal restraint and economic growth alone could cut at most half, according to a September 2015 government report. Thus, most discussions have focused on methods for renegotiation: extending the maturity of debt (thereby lowering the amount per payment), reducing the amount of interest or principal, or refinancing the debt with new loans. Renegotiation can be mutually beneficial when the alternative is default or costly lawsuits.

Restructuring is no easy task, however. "Getting a handle on the structure of Puerto Rico's debt is difficult. There are some 18 different issuers, and transfers of assets further complicate the picture," says Andrew Austin, an economist with the Congressional Research Service. The island's public electric utility, PREPA, has gone to creditors directly to try to renegotiate its debt, amounting to about an eighth of total public sector debt. So far, it has met its payments, at times with help from its creditors. This progress provides a ray of hope that a broader framework for restructuring could also succeed, Austin argues. At the same time, he notes that different sets of creditors have different interests, and without an outside adjudicator, a debt restructuring deal may be difficult to obtain before the island government runs out of liquidity completely.

Hence, the question of municipal bankruptcy through Chapter 9 of the Bankruptcy Code has come into focus. In Chapter 9, a municipality seeks, with a state's permission, to use the court system to renegotiate debts and determine creditor priority, maximizing the municipality's ability to continue functioning. Since it was established by legislation in 1937, Chapter 9 has assisted well over 600 U.S. municipalities and their instrumentalities — most recently in Detroit. One of its potential advantages is that it requires only a majority of creditors to approve a deal, preventing minority interests from blocking a deal or dragging out talks.

But this route is currently unavailable to Puerto Rico: Its municipalities cannot qualify for Chapter 9 because Puerto Rico is not a U.S. state. And states, which have greater independent resources for revenue generation, are precluded from declaring bankruptcy for reasons dating back to constitutional safeguards that prevent states from diluting the power of contracts by, for example, writing off their own debts. For the most part, defaulting U.S. states have been left to fend for themselves, although Arkansas — the most recent state to default — received help from the Depression-era Reconstruction Finance Corporation in 1933. Bailouts occurred in the late 1700s, but nine states famously defaulted in the 1840s after a banking panic and the federal government's refusal of a bailout, which economists argue created a lasting precedent forcing states to manage their own budgets more closely.

Access to Chapter 9 is a divisive issue in Congress. "Lawmakers don't want to be seen as supporting anything that looks like a bailout," Skeel says. "Critics of giving Puerto Rico or its municipalities a bankruptcy option have framed bankruptcy as a bailout — wrongly, in my view." Many creditors with seniority, including hedge funds that stepped in after ratings agencies downgraded Puerto Rican debt in 2013, worry that their priority would be overturned or that they would be forced to accept a haircut on what they are owed.

Even if Chapter 9 relief is extended to Puerto Rico, it's not clear that would be the end of the problem. The municipal debt that would potentially be relieved under that option is less than 7 percent of the island's total public debt. "Unless Congress amends the Bankruptcy Code to allow Puerto Rico's central government and its public corporations, not just its municipalities, to receive assistance, Chapter 9 will not suffice," says Maurice McTigue of George Mason University's Mercatus Center.

Taking The Reins

Ultimately, the United States may have to consider unorthodox measures to resolve the crisis. Control boards are one. Another, a proposal recently floated by the U.S. Treasury Department, would have the United States issue new "superbonds" to Puerto Rico's creditors in exchange for their existing bonds, effectively consolidating creditors under one group of obligations. Treasury would oversee a portion of the island's tax revenue and place it in an escrow account to make sure it is used for repayment. U.S. taxpayers would not be on the hook, but Treasury argues that its supervision would make this route more attractive for creditors than accepting bonds issued by the Puerto Rican government.

In the near term, creditors and policymakers alike will be looking to a U.S. Supreme Court decision later this year that may shape future debt talks either way. The court will decide a case, Puerto Rico v. Franklin California Tax-Free Trust, concerning whether the island's utilities can renegotiate their debt through Puerto Rico's legal system using an alternative to federal bankruptcy that island lawmakers set up in 2014. If the court overturns a lower-court decision, it would provide an avenue for about $20 billion in obligations to be restructured.

Regardless of what U.S. policymakers decide, Skeel wagers that the island will continue efforts to put its fiscal situation on a more sustainable footing. But he says the outcome if no debt restructuring occurs is simple: "Puerto Rico would continue to cut services and lose population."

![]() " Congressional Research Service, Sept. 25, 2015.

" Congressional Research Service, Sept. 25, 2015. ![]() " Government Development Bank for Puerto Rico, June 29, 2015.

" Government Development Bank for Puerto Rico, June 29, 2015.