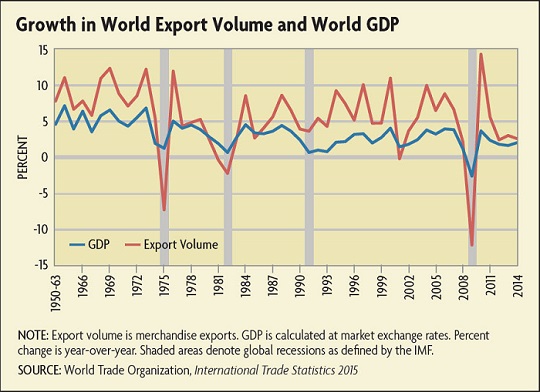

Why did trade fall so steeply in 2008 and 2009? Largely, it was due to weak demand. About 70 percent of the decline can be explained by changes in demand, according to a 2010 article by Rudolfs Bems of the International Monetary Fund, Dartmouth College's Johnson, and Kei-Mu Yi of the University of Houston. The drop in demand translated disproportionately to a drop in trade as a result of "composition effects": During recessions, businesses and consumers tend to cut back more on investment and durable goods, such as new equipment or cars, than they do on consumption goods. But durable goods tend to be much more heavily traded than nondurable goods and also rely more on imported inputs for production. As a result, declines in investment and durable goods purchases can have an outsized effect on trade.

Why is Trade Growth Still Slow?

Weak demand can explain much of the Great Trade Collapse. But why, after a brief rebound, is trade growth still slow?

In part, trade growth might be slow because GDP growth in advanced economies is still relatively slow. Recent research by Patrice Ollivaud and Cyrille Schwellnus, economists at the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, found that trade growth since the crisis is close to predicted values based on certain ways of measuring global GDP growth.

Weak demand from European countries might be having an especially large effect on measures of global trade growth. Overall, the 19 euro area countries have averaged just 0.8 percent GDP growth between 2010 and 2015, compared with 2.2 percent between 2000 and 2007, according to data from the International Monetary Fund. A fall in European demand has a disproportionate impact on world trade numbers since it reduces both imports from outside the euro area and intra-euro area trade, which is 10 percent of global trade. In Ollivaud and Schwellnus' analysis, this is because the members of the euro area are treated as separate countries for the purposes of measuring trade, despite the fact that intra-eurozone trade is akin to intra-national trade in that there are no tariffs, the currency is the same, and transportation costs are low. Ollivaud and Schwellnus found that if intra-eurozone trade is excluded, post-crisis global trade intensity (measured as the ratio of import volume to GDP volume) is only slightly below its pre-crisis trend.

Weak demand, along with a strong yuan, also has depressed exports from China, and there are signs of longer-term changes in the Chinese economy. "Two dimensions of the Chinese economy have changed," says the University of Houston's Kei-Mu Yi. "First, as they've become more technologically proficient, they can make a lot of the intermediate inputs themselves, and to the extent they do, their demand for imports would fall. Second, as their economy has gotten bigger, they are selling more domestically rather than exporting." Just as China's entry into the global market boosted trade for the world as a whole, a persistent decrease in China's trade could depress global trade growth.

Have We Reached Peak Trade?

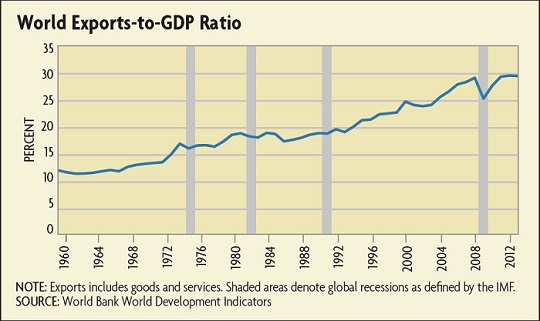

Just how much trade elasticity has declined, and when that decline started, is the subject of considerable debate among economists. But some research suggests the process actually started well before the global financial crisis. With Cristina Constantinescu and Michele Ruta, also of the World Bank, Mattoo found that the trade elasticity started falling around 2001, to about half of what it was between 1986 and 2000. According to their analysis, this decrease in elasticity explains about half of the trade slowdown in 2012 and 2013.

The authors pointed to a slowdown in the adoption of GVCs as one major reason the trade elasticity has decreased. Comparing the elasticity of gross trade to the elasticity of value-added trade, which has been relatively stable over time, they find the measures have converged since the early 2000s, suggesting a slower pace of vertical specialization.

Partly, that's just mathematical. "When offshoring is new, you end up with this big boost in gross trade as you're increasing the round-tripping of the parts," says Freund. "But once global value chains are established, the base is so much bigger that growth is going to look a lot slower."

But it also could reflect that businesses have become slower to adopt GVCs or are pulling back from them altogether. First, the returns might have shrunk, as companies have already adopted GVCs for the products where gains are most likely to be realized. In addition, rising labor costs in developing countries could alter the calculation; hourly manufacturing wages in China, for example, have increased on average 12 percent per year since 2001. Natural disasters such as the Fukushima earthquake also could make managers nervous about having long supply chains. Anecdotally, a number of American companies have been "reshoring" manufacturing to the United States. The Reshoring Initiative, an advocacy group, estimates that about 248,000 jobs that left the United States have returned since 2010.

While Constantinescu and her co-authors pinpointed 2000 as the beginning of the decline in the trade elasticity, other research has found that the decline did not occur until the Great Trade Collapse. In this view, the decline is still attributable to a pullback from vertical specialization, but that itself might be for cyclical reasons. Whether vertical specialization — and with it the trade elasticity — will accelerate when and if global demand picks back up remains to be seen.

"When you look at what's been happening in the global economy over the past decade, it's possible to be a little pessimistic and conclude that the globalization movement since World War II is not just an inevitable force that won't be stopped," says Yi.

Still, there are factors that could lead to faster trade growth in the future. For example, technology has made it increasingly possible for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to reach customers around the world. (International organizations generally define a medium-sized enterprise as one with fewer than 250 employees and a small enterprise as one with fewer than 50.) SMEs continue to account for only a small portion of trade relative to their share of businesses in the economy; in the United States, for example, SMEs are more than 99 percent of all businesses, while accounting for only about 15 percent of exports and 10 percent of imports. Policy changes that make it easier for SMEs to participate in international trade, such as raising the threshold above which an importer must pay customs duties, reducing trade compliance costs, or harmonizing postal systems, could help boost trade growth.

Another potential source of trade growth is trade in services, such as computer programming or accounting. Services trade has grown more quickly than merchandise trade since the 1980s and equaled about 13 percent of world GDP in 2014 — still small relative to services' 70 percent share of the world economy. "The scope for liberalization in services is still quite large," says Mattoo. Reductions in barriers to trade in services, such as the Trade in Services Agreement currently being negotiated by 23 members of the WTO (including the United States), could lead to greater trade growth.

Finally, it's possible that other developing countries could eventually increase their manufacturing base and their participation in world trade. "South Asia, Latin America, and Africa haven't really participated in the finer and finer international division of labor that has been made possible by global fragmentation," says Mattoo. "So there is the potential to expand supply chains elsewhere in the world. That could unleash another burst."

Trade Matters

Underlying the debate about whether or not trade growth will accelerate is the question, does the amount of trade matter? "It matters to the extent it improves our standard of living," says Yi. "What ultimately matters is consumption, how much people are eating, spending, and enjoying life. Trade plays a significant role in increasing consumption. But that doesn't necessarily require global trade to be growing faster than global GDP."

At the same time, says Yi, "The period when the global economy did really well happened to be the period when globalization increased a lot. Was it just an accident that the global economy did really well when global trade did really well, or are they somehow connected?"

There is a strong consensus among economists, dating back to Adam Smith, that trade is beneficial because it allows countries to specialize in producing those goods for which they have a comparative advantage. In 1776, Smith wrote, "If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry employed in a way in which we have some advantage." Trade also gives firms access to new markets and can increase productivity via technology spillovers from imports, as well as competitive pressures. Slower trade growth thus could limit an important channel for productivity growth.

In addition, research suggests that trade can be an important avenue of economic growth, especially for developing countries. "From that perspective," says Freund, "trade slowing down bodes ill for the developing countries. We've seen a lot of countries that have grown primarily through trade, and if trade is really slowing down it makes it harder to follow that model." Between 1981 and 2010, for example, China's growth pulled nearly 700 million people out of poverty. The presence of GVCs in particular might be important for developing countries, because they allow a country to industrialize without having to develop a diversified manufacturing base from scratch. As Richard Baldwin of the Graduate Institute Geneva described it in a 2011 paper, countries can join a supply chain rather than build an entirely new one.

In addition, it has long been conventional wisdom in some branches of political science that trade promotes peace because it increases the opportunity cost of armed conflict. This view underpinned the formation of European Economic Community in the 1950s and continued to motivate European leaders even decades later. As Jacques Delors, former president of the European Commission, stated regarding the introduction of the euro, "The argument in favor of the single currency should be based on the desire to live together in peace."

There is some empirical evidence to support this view. For example, between 1950 and 2000, wars occurred only about one-tenth as frequently as between 1820 and 1949. While a variety of political, technological, and economic changes occurred during this period, the decrease could be attributed to the increasing density of international trade networks, according to a 2015 article by Matthew Jackson and Stephen Nei of Stanford University. Using game theory, Jackson and Nei compared alliances based on military incentives alone to alliances augmented by international trade and found that the latter are significantly more stable. The authors also found that the regions with the most armed conflicts, such as central Africa, have relatively few trade ties, which suggests that countries could benefit from more than the development opportunities afforded by trade.

Still, trade doesn't necessarily prevent war. The "first wave" of globalization occurred between 1870 and 1913, and "Many pundits thought economic ties between the European nations were too strong to have a war," says Yi. "But of course they were wrong."

The many benefits of trade are why the Great Trade Collapse of 2008-2009 — and sluggish trade growth thereafter — attracted so much attention from economists and policymakers. And while economists have largely reached a consensus that the initial collapse was the result of weak demand, there is still considerable debate about why trade growth today remains slow and what it might mean for the future.

![]() ." IMF Economic Review, December 2010, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 295-326.

." IMF Economic Review, December 2010, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 295-326.![]() London: Center for Economic Policy Research Press, 2015.

London: Center for Economic Policy Research Press, 2015.![]() available online.)

available online.)