Paying for World War I: The Creation of the Liberty Bond

Editor’s Note: A version of this article first appeared on the Federal Reserve History website. The author is the Edward A. Dickson Distinguished Emeritus Professor of Economics at the University of California, Riverside and a visiting scholar at UC Berkeley.

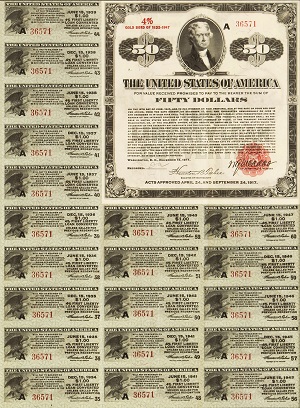

World War I began in Europe in 1914, the same year the Federal Reserve System was established. During the three years it took for the United States to enter the conflict, the Fed had completed its organization and was in a position to play a key role in the war effort. Wars are expensive and, like every governmental effort, they have to be financed through some combination of taxation, borrowing, and the expedience of printing money. For this war, the federal government relied on a mix of one-third new taxes and two-thirds borrowing from the general population. Very little new money was created. The borrowing effort was called the "Liberty Loan" and was made operational through the sale of Liberty Bonds. These securities were issued by the Treasury, but the Fed and its member banks conducted the bond sales.

Generally speaking, the secretary of the Treasury proposes a funding plan for war financing and works with Congress to enact the necessary legislation, while the Fed operates with considerable independence from both the executive and legislative branches of government. But World War I was different. The Treasury and the Fed, united under one leader, worked together in both the creation of the financial war plan and its execution.

Rejecting Printing-Press Finance

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, it became immediately evident that an unprecedented effort would be required to divert the nation’s industrial capacity away from meeting consumer demand and toward fulfilling the needs of the military. At the time of the congressional declaration of war, the American economy was operating at full capacity, so the requirements of the war effort could not be met by putting underutilized resources to work. William Gibbs McAdoo, secretary of the Treasury and chairman of the Fed’s Board of Governors, understood that the wartime population would have to sacrifice to pay the bill. Shortly after war had been declared, he delivered a speech that he later recorded for posterity:

"We must be willing to give up something of personal convenience, something of personal comfort, something of our treasure — all, if necessary, and our lives in the bargain, to support our noble sons who go out to die for us."

But the question remained: How would the shift in output be arranged? How should the war be paid for? There were three possibilities: taxation, borrowing, and printing money.

For McAdoo, printing money was off the table. The experience with issuing "greenbacks" during the Civil War suggested that fiat money would generate inflation, which he thought would lower morale and damage the reputation of the newly issued paper currency, the Federal Reserve Note. McAdoo also opposed printing money because it would hide the costs of war rather than keeping the public engaged and committed. "Any great war must necessarily be a popular movement," he thought, "… a kind of crusade."

McAdoo chose a mix of taxation and the sale of war bonds. The original idea was to finance the war with an equal division between taxation and borrowing. Taxation would work directly and transparently to reduce consumption. Taxes are compulsory, and those who must pay are left with less purchasing power. Their expenditures will fall, freeing productive resources (labor, machines, factories, and raw materials) to be employed in support of the war. Another advantage of taxation was that Congress could set the rate schedule to target those they thought should bear the greatest burden. President Woodrow Wilson and the Democrats in Congress insisted on a sharply progressive schedule — taxing those with very high incomes at higher rates than the middle class and exempting the poor. The highest marginal rate eventually reached 77 percent on incomes over $1 million.

Accompanying the personal income tax was an increase in the corporate income tax, an entirely new "excess-profits tax," and excise taxes on such "luxuries" as automobiles, motorcycles, pleasure boats, musical instruments, talking machines, picture frames, jewelry, cameras, riding habits, playing cards, perfumes, cosmetics, silk stockings, proprietary medicines, candy, and chewing gum. These taxes ranged from 3 percent on chewing gum and toilet soap to 100 percent on brass knuckles and double-edged dirk knives. A graduated estate tax on the transfer of wealth at death exempted the first $50,000 and rose progressively thereafter from 1 percent to 25 percent.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.