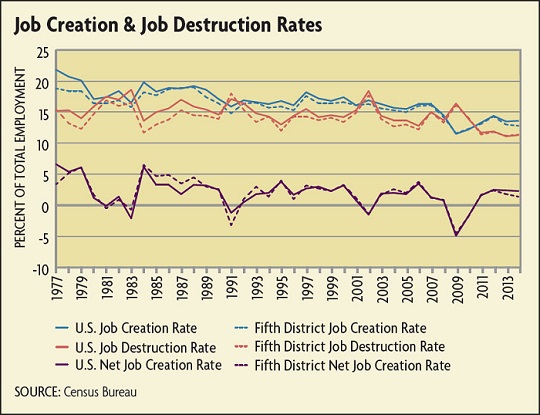

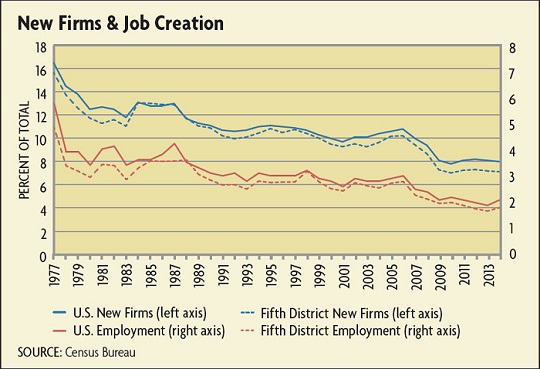

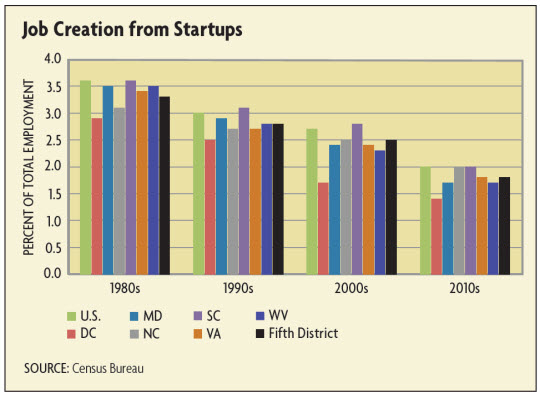

Declining startup activity has hurt job growth. In a 2010 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, John Haltiwanger of the University of Maryland and Ron Jarmin and Javier Miranda of the Census Bureau found that "firm births contribute substantially to both gross and net job creation" and that startups play a "critical role" in U.S. employment growth dynamics. For those startups and younger firms that survive, their growth rate is considerably higher than that of more mature firms. In that paper, they found that business startups account for roughly 3 percent of total employment in any year from 1992 to 2005. But that percentage was higher prior to 1992, averaging close to 4 percent prior and averaging just 2 percent from 2006 to 2014.

So what has been the cause of the slowdown in business dynamics and the decline in new firm formation? There has been no definitive accounting for the dynamics of firm entry and exit and the trends observed in the data. In a 2013 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, Daron Acemoglu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ufuk Akcigit of the University of Chicago, Nicholas Bloom of Stanford University, and William Kerr of Harvard Business School looked at innovation and productivity growth to explain firm entry and exit. They found that policies that subsidize either the research and development or the continued operation of incumbent firms stifle the formation of new firms. They argued that incumbent firms that are slow to innovate use research and development resources inefficiently. Eliminating subsidies would free up these resources for incumbent firms that are more innovative as well as for new firms.

Similarly, a 2006 article by Haltiwanger and Lucia Foster and C.J. Krizan of the Census Bureau in the Review of Economics and Statistics looked at the restructuring in the retail trade sector in the 1990s and found that much of the restructuring was due to more productive establishments entering the market to displace existing establishments that are less productive. They noted that the "productivity gap between low-productivity exiting single-unit establishments and entering high-productivity establishments from large, national chains plays a disproportionate role in these dynamics."

In a 2004 article in Annals of Regional Science that examined the determinants of new firm formation in the manufacturing sector in Texas from 1970 to 1991, Donald Hicks of the University of Texas at Dallas and Vinod Sutaria, then a doctoral student there, looked at a number of factors to explain firm formation: demographics, labor market conditions, industrial restructuring, availability of local finance, local government spending, and local business dynamics. They found that new firm formation was reduced by rising unemployment rates in a metro region and was boosted by higher average establishment size and availability of capital (as measured by local per capita bank deposits) in a metro region. They also found that population and per capita personal income growth were not factors that influenced new firm formation.

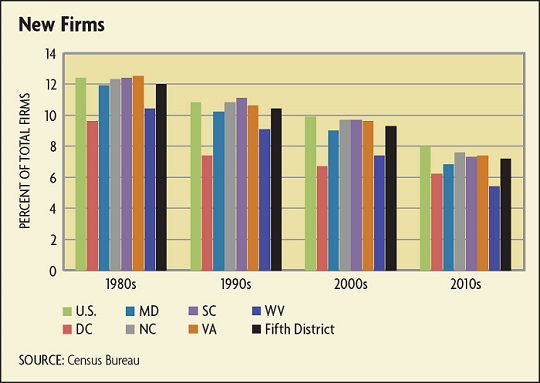

In a 2014 paper, Ian Hathaway of the Brookings Institution and Robert Litan, formerly at Brookings, used the BDS data to look at the variation in startup rates across U.S. metropolitan areas and found two prominent drivers of regional differences: population growth and business consolidation. Contrary to the results of Sutaria and Hicks, Hathaway and Litan found that firm formation tends to be higher in regions with greater population and real per capita income growth. They noted that regions with the highest firm entry rates in the late 1970s were strongly correlated with population growth in the 1970s, and the opposite was true for regions with lower firm formation rates. They ran several regressions and in one found that the change in population from the late 1970s to the mid-2000s had a large positive effect on startups. When they accounted for region-specific effects, they found that the estimated impact of population change over the prior three years is reduced but still strong and statistically significant. They also find that income per capita is a significant factor, although they estimate that the impact of population change is three times greater than income per capita.

Hathaway and Litan also looked at the possible effect of an aging population. Prior research has suggested that individuals age 35 to 44 have the highest propensity to start a new business. To examine the possible impact of an aging population on startup activity, they included that age group in their regressions and found that when controlling for regional factors, the share of the population between 35 and 44 does greatly influence firm formation rates — and the impact is greater than that of per capita income growth.

The other significant driver of new firm formation in their results is business consolidation. In previous work, Hathaway and Litan documented an increase in business consolidation across geographies and sectors over the past few decades. They found that the firm formation tends to be higher in regions with less business consolidation. They defined business consolidation as an increase in the ratio of the average firm size to the average establishment size. A ratio of 1.0 would indicate no consolidation as each firm has one establishment. As the ratio increases, there are more multi-establishment firms. They argue that greater concentration would be associated with higher barriers to entry and thus would reduce firm formation.

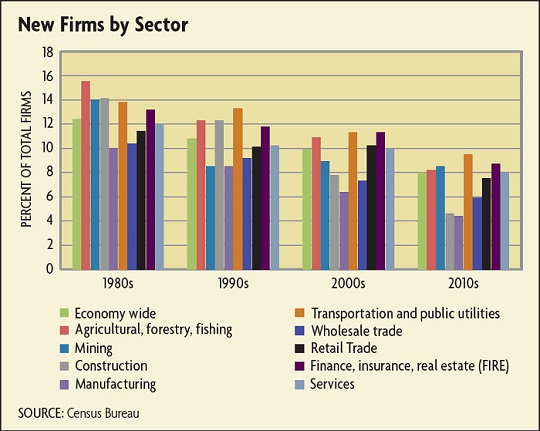

Slowdown Across Sectors

The long-term slowdown in business dynamism and startup activity has been observed across industries. Each industry sector has experienced a decline in its firm formation rate, although there are some notable differences across industries. (See chart below.) Comparing the 1980s to 2010-2014, the average decline was 5.4 percentage points, with the goods-producing sectors experiencing the largest declines. The greatest decline was in the construction sector. In the 1980s, the startup rate in the construction sector averaged 14.1 percent — the second-highest rate after agricultural, forestry, and fishing and just slightly above mining. The construction startup rate fell by 9.6 percentage points to an average of 4.6 percent in 2010-2014, the second-lowest rate among all industries. Startup activity in the agricultural, forestry, and fishing sector experienced the second-largest decline, by 7.3 percentage points.