The Resurgence of Universal Basic Income

Concerns about the effects of automation have brought an old policy proposal back into the limelight

The idea that technology will make human workers obsolete is certainly not new. In the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes wrote, "We are being afflicted with a new disease of which some readers may not yet have heard the name, but of which they will hear a great deal in the years to come — namely, technological unemployment." Keynes thought that technology would replace workers faster than workers could find new jobs. But he optimistically believed that this process eventually would lead to an "age of leisure and of abundance."

Today, a new set of techno-optimists argue that coming advances in automation and artificial intelligence will finally fulfill Keynes' prediction, replacing most human labor. Even if machines don't cause widespread unemployment, they have caused and surely will continue to cause substantial labor market shocks in specific industries. These concerns have breathed new life into the discussion over a policy now called universal basic income, or UBI.

Many variations have been proposed, but UBI generally refers to regular cash payments that would go to individuals regardless of work status or income (that's the "universal") and would cover some minimum standard of living (that's the "basic"). Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and other figures in the tech industry have publicly announced their support for UBI as a result of their concerns about job loss from automation. As workers are replaced by machines, "we need to figure out new roles for what those people do, but it will be very disruptive and very quick," said Musk in a 2017 speech in Dubai. "I think we'll end up doing universal basic income … it's going to be necessary."

At the same time, questions remain about how it could be done and its effects.

UBI Meets U.S. Politics

It wasn't technology leaders or futurists who first brought UBI into mainstream U.S. political discourse — it was economists. Milton Friedman first proposed the negative income tax (NIT), a forerunner of UBI, in his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom. The NIT and UBI are identical, except that NIT benefits would decrease as a recipient's income increases and at a certain level phase out entirely, while UBI payments would be fixed regardless of income. Economists from all over the ideological spectrum came to support NIT proposals, including Friedman's fellow Nobel laureate Friedrich Hayek as well as liberal-leaning economists like Nobel laureates Paul Samuelson and James Tobin. In 1968, more than 1,200 economists signed a manifesto advocating for a guaranteed income.

Support from economists and policy experts eventually led to a political movement. At the urging of Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.), President Nixon presented the Family Assistance Plan (FAP) in 1969; the program would have provided each family in America $1,600 per year (roughly $10,650 in today's dollars) subject to some work requirements. Shortly after, a more generous proposal called the Human Security Plan was proposed by Sen. George McGovern (D-S.D.), part of his presidential campaign platform as the Democratic nominee in 1972. Despite economists' support for the Moynihan plan, no guaranteed income plan ever made it through Congress.

Proponents made many arguments for basic income. One was that basic income would be more efficient than the welfare system as it would require very little bureaucracy. Although lower administrative costs might be a benefit of UBI, it probably would not be a large one. According to Jason Furman, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers during the Obama administration and now senior fellow at the Peterson Institute, eliminating the entire administration for unemployment insurance, food stamps, housing vouchers and the like would provide an annual UBI of only about $150 per person.

One of the main concerns about UBI has been its effect on work and labor supply. In 1986, Alicia Munnell, then senior vice president and research director at the Boston Fed, said basic income schemes have been beset by "the widespread fear that a guaranteed income would reduce the work effort of poor breadwinners and, as a result, cost taxpayers a great deal of money." This objection is still shared by many today, but it was the exact opposite of what supporters expected: They thought that replacing the U.S. welfare system with a guaranteed income might actually give the poor more reason to work. "I see the work incentive for low-income families as the single biggest economic benefit of replacing the current system with a UBI," says Ed Dolan, an economist at the libertarian-leaning Niskanen Institute in Washington, D.C., and a prominent proponent of UBI.

Why the disconnect? It's rooted in opposing beliefs about how workers would respond to the payments — and how they respond right now to welfare programs.

If you suddenly start receiving an extra check in the mail every month, such as a UBI, you can suddenly consume more for any given amount of leisure, and you can afford to work less. This — what economists call an "income effect" — is what many skeptics have in mind when they worry that UBI would cause people to work less or stop working altogether.

But if that check comes as part of a means-tested program, like a traditional welfare program, then the payment goes down as you earn more. From your perspective, the declining welfare payment is equivalent to an increase in marginal tax rates. The more you work, the less you get to keep of each dollar earned, and you might rationally choose to work less. This is a substitution effect: As work becomes relatively less profitable, you substitute toward leisure.

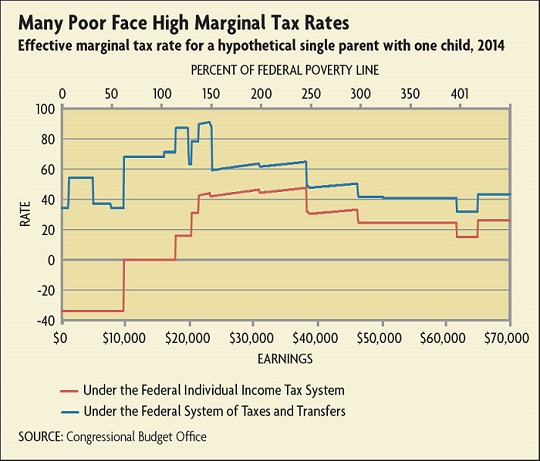

The substitution effect is a major concern that many economists have with the current U.S. welfare system: Many poor people face high effective marginal tax rates. Data from the Congressional Budget Office show that the effective marginal tax rate for a single parent with one child changed with their earned income in 2014. When including federal transfer payments, this effective marginal tax rate nears 100 percent at low incomes — a hypothetical family nearing 150 percent (about $23,000) of the federal poverty line would keep less than 10 cents of each extra dollar they earned. (See chart below.) There are also other large cliffs in effective marginal tax rates, which vary widely by state and almost always fall below 150 percent of the poverty line: losing eligibility for Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly "food stamps"), Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), and state transfers.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.