The Rise and Decline of Petersburg, Va.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, [LC-DIG-cwpb-02280; LC-DIG-cwpb-02281.]

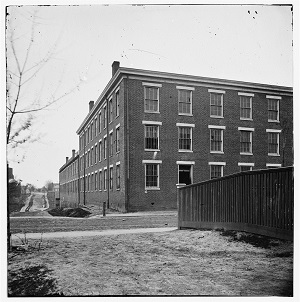

Tobacco warehousing and manufacturing have long been part of Petersburg’s economic history. This image, from 1865, shows a tobacco warehouse on High Street that was used as a temporary prison.

Early Virginians looked at Petersburg, with its location on the Appomattox River, as a town of economic vibrancy and promise. Incorporated in 1748 by the Virginia General Assembly, the town fulfilled that early promise and grew to become the commonwealth's third independent city in 1850. But turmoil as well as prosperity for Petersburg were ahead.

Throughout its 270 years, three factors have dominated Petersburg's economic history: tobacco, trade, and transportation. The city's early economic prominence was due to its tobacco plantations and warehouses as well as various mills powered by the river's falls. Later, the mills were replaced by other types of manufacturing. Petersburg remained a transportation hub throughout the evolution from canal boats to railroads to interstate highways. It also became a busy retail center, beginning as a fur trading post and later broadening its activities to more general retail and wholesale trade. And all along, Petersburg was near tobacco cultivation and involved in manufacturing of tobacco products.

The city's specialization in a small number of sectors has, however, made the city vulnerable to negative economic shocks, and these ultimately explain a large part of the city's fiscal struggles from the 1980s onward. When economic and social developments led the city's businesses, and later its wealthier households, to move out, Petersburg was confronted with the loss of a sizeable amount of its tax base. This, combined with reported local mismanagement of the city's public finances, resulted in a slow but steady deterioration of the quality of life for those who remained in the area.

Early Petersburg

When the English arrived in Virginia in 1607, the area south of the Appomattox River was occupied by the Appamatuck, a tribe of the Powhatan Confederacy. By 1638, Abraham Wood, proprietor of an early frontier outpost, had legally claimed the site. Nearly three decades later, Wood's son-in-law established a fur and Indian trading post called Peter's Point adjacent to the falls of the Appomattox River, and in 1733, William Byrd II laid the plans for the town named "Petersburgh" (as it was then spelled).

Tobacco plantations arose in the surrounding areas, and warehouses soon sprung up around Petersburg to facilitate tobacco transport to coastal ports and, from there, to England. Around that time, numerous water-powered mills arose in the area, manufacturing various products including cloth and cornmeal. In 1816, a series of canals and locks were constructed around the falls that allowed bateaux and canal boats to conduct trade between Petersburg and towns farther west along the river. By 1830, the Petersburg Railroad was incorporated and the town soon became a major transfer point for both the north-south and east-west railroad lines.

These developments laid the foundation for continued growth. The census of 1860 listed 9,342 whites and 8,924 blacks in Petersburg, making it the second-largest city in Virginia. With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Petersburg's pre-eminence as a major railroad depot made the city important to Confederate supply lines and, consequently, a strategic objective of the Union Army. In June 1864, the Union Army outflanked the Confederate defenses, and the result was a siege of the city that would last until April 1865. During this time, Petersburg was subjected to almost daily shelling, directed not only toward military targets such as railroad depots and supply warehouse, but also toward public buildings and residential sections. The war devastated Petersburg, resulting in a slowdown of population growth for a prolonged period.

After a time, however, Petersburg's economy recovered during the postwar years. The early water-powered mills were replaced by other types of manufacturing during this period, and the role of trade was boosted by new merchants emigrating from Europe. Within a few decades, Petersburg and its surrounding communities again became a thriving manufacturing and raw materials processing center, generating numerous smaller businesses specialized in ironworks, sand and gravel production, and trade in cotton and peanuts.

A Second Tobacco Boom

Moreover, tobacco warehousing and manufacturing again became the major local industry. By the late 19th century, farmers from the Carolinas began to cultivate bright leaf tobacco that was better suited to the production of increasingly popular cigarettes. Soon, cigarette manufacturing began to supplant the production of plug and twist tobacco (or "chewing tobacco") in the city. With its well-developed transportation facilities, Petersburg became a dominant market for bright leaf auctions and had stemmery and leaf dryer facilities that added to its tobacco economy.

But by the turn of the 20th century, the tobacco industry was consolidating; most of the family-owned tobacco companies in Petersburg were acquired by the newly created American Tobacco Co. and became part of the "Tobacco Trust." In 1902, the British-American Tobacco Co., or BAT, was established by an agreement between the Imperial Tobacco Co. of Great Britain and the American Tobacco Co. and its subsidiaries. In 1910, BAT moved its cigarette plant to Petersburg; the plant manufactured cigarettes for export primarily to China and Australia, and the plant quickly became the city's largest employer and biggest taxpayer. By 1930, the changing economic and political conditions, primarily in China, caused this operation to be discontinued. Fortunately for Petersburg, Brown and Williamson Tobacco Co. (B&W) took over the shuttered BAT plant in 1932, replacing its predecessor as chief taxpayer and employer in the city.

As the automobile began to dominate transportation in the early 20th century, three main highways (U.S. Routes 1, 301, and 460) intersected at Petersburg's center. These crossroads effectively made Petersburg the urban core of "Southside Virginia" and led its downtown area to become a thriving retail and professional center. By 1950, the population of Petersburg increased to 35,054, surpassing the previous peak reached in 1920. Another phase of highway development played out badly for the city, however: In the late 1950s, the newly constructed Interstates 95 and 85 converged at Petersburg but bypassed the city's downtown area, eroding the city's retail potential as well as that of its professional services. Middle and upper classes started to shift away from the city.

As Petersburg entered the second half of the century, significant social and economic changes were underway. The United States Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision ruled that the "separate but equal" doctrine in public schools was unconstitutional. In a 1996 history of school desegregation, University of Richmond law professor Carl Tobias noted, "The Petersburg School Board, like numerous others, developed and applied several stratagems for maintaining segregated public education." But by 1970, considerable integration of Petersburg's schools had occurred and "white flight" to nearby less racially diverse areas began in earnest. The composition of the city's population shifted to primarily black.

In 1972, a crucial decision occurred that was to have long-lasting implications for the city's finances. That year, the city annexed 14 square miles from neighboring Dinwiddie and Prince George counties, ostensibly to add large tracts of vacant land for industrial development and to expand its property tax base. This annexation almost tripled the geographic size of the city but added only 7,300 new citizens. But "white flight" and the shift of jobs away from the downtown area (often referred to as "job sprawl") continued as manufacturing operations in Petersburg and the surrounding communities began to close or downsize.

The Economic Tide Goes Out

In 1985, B&W consolidated its operations in Georgia and permanently closed its Petersburg plant. This was a major blow to the city — a decade before, B&W's Petersburg facility employed as many as 4,000 workers. Adding to these woes, Petersburg's proximity to Richmond — which had grown to dominate the region — hampered its ability to attract new firms and retain residents.

In the decades following Petersburg's annexation and the closure of the B&W plant, the city began to experience a slow and prolonged period of job losses and urban decline. Substantial economic development in the annexed area never materialized and the costs to provide and maintain infrastructure in this new part of the city weighed on Petersburg's fiscal budget. The city also had to address an abundance of deteriorating and abandoned properties, which contributed to lower property values and led to further downward pressures on tax revenues.

As job prospects in the city waned, residents left. After peaking at 46,267 in 1975, Petersburg's population fell for the next 30 years, stabilizing at around 32,000 in 2005. Younger residents left to a greater extent than others, and the proportion of the population that was 65 or older reached 16 percent by 2016 — up from 10 percent in 1970. Educational attainment also slipped, with the proportion of residents graduating from college declining relative to statewide averages.

Inner-city blight, including increased unemployment, crime, and property abandonment, contributed to racial and social problems, and political turmoil emerged in Petersburg over time. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, the city had the highest concentration of poverty in the region at 21.5 percent, and it had an unemployment rate of 8.1 percent in mid-2016 — nearly double the statewide average.

High unemployment and a declining population negatively affected Petersburg's housing sector. While the total housing stock in Petersburg has edged up in recent years, the fundamentals driving prices — incomes and proximity to jobs — generally only limited appreciation in home values and, as a consequence, limited growth in tax revenues.

Effects on Local Public Finances

The combination of these developments led to a slow, steady deterioration of the city's public finances. To be sure, it is common for cities to undergo cyclical periods of economic stress, which ultimately affect their finances; local revenues fluctuate as national and local economic conditions change, for example. But the underlying factors behind the deterioration of Petersburg's local fiscal health appear to be intrinsically structural. The exodus of high-income households and firms has weakened the city's tax base. In turn, the households that remain are disproportionately lower income and older, requiring more services from the local government. As a result, the decline of the city population has not been matched by reduced pressures on local government expenditures. In fact, all these factors have tended to increase the cost per resident of providing local services, imposing a significant financial stress on the city's budget.

The heightened financial pressures became evident by 2009 as tax revenue fell short of expenditures. The city responded by taking money from its general funds balance, issuing short-term debt, and deferring capital maintenance. The delayed maintenance of an aging infrastructure eventually strained the city's ability to deliver basic services. These developments underpinned several recent events that have garnered widespread public attention, such as a failing of the water system and substantial problems with the performance of the city's public schools.

As weakened local public finances translated into a lower quality of local public services, the city became less attractive to its remaining residents, explaining part of the slow exodus of firms and households during the period. The local public finance channel, in this way, magnified and reinforced the initial negative effects. To address these recurring shortfalls, the city repeatedly drew down its cash reserves, leading rating agencies to downgrade Petersburg's debt.

Maintaining fiscal discipline in a city facing these structural economic problems has been challenging. The lack of comprehensive financial controls and the failure to adhere to sound budgetary rules worsened fiscal imbalances, transforming serious but potentially manageable economic problems into a crisis. In addition, conditions can worsen if local residents and officials do not promptly realize that these local economic challenges will likely be long lasting, resulting in a failure to implement the appropriate adjustments.

To some extent, Petersburg responded to the fiscal challenges in a similar way to other cities in comparable situations. When faced with deteriorating local public finances, local officials, driven perhaps by political motivation, often try to develop short-term crisis solutions, which temporarily disguise the problems. This kind of behavior entails postponing the necessary decisions required to address the long-term imbalances, perhaps pushing them beyond the next election. But such a short-term approach can lead to the implementation of unsustainable policies that jeopardize the cities' longer-term economic prospects.

Looking ahead, Petersburg may well continue to face demographic and social headwinds. If current trends continue, the combination of an aging population and lower educational attainment will likely limit the attractiveness of the city to potential relocating businesses. If younger residents anticipate this, they will more likely locate away from the city. Additionally, continued delays of infrastructure maintenance and a lack of improvement in school performance could leave residents with compromised public services and somewhat limited skill sets. If this, in turn, is reflected in lower tax revenues in the future, the city's current set of problems could persist and be compounded.

Challenges of a Small, Specialized City

In many ways, Petersburg's experience is typical of that of other cities during comparable economic downturns. Petersburg is an example of an older, smaller city whose economic growth historically depended on a narrow set of economic activities, specifically, trade, tobacco, and textiles. These cities are often described as "specialized" cities. (See "Diversification and Specialization Across Urban Areas.")

Cities with a disproportionate presence of a small number of large firms concentrated in just one or two sectors are more vulnerable to economic shocks. Clearly, in the last 50 years, technological changes and globalization have affected these cities to a greater degree than diversified cities. Another implication of this kind of local economic structure is that when those particular sectors go through good times, residents of those locations may not have strong incentives to acquire higher levels of education. To the extent that those industries offer relatively well-paying job opportunities to young residents with low-to-moderate skills, these residents might pursue those opportunities and perhaps acquire less additional education, anticipating little payoff from it. Such an approach could make residents more vulnerable to negative shocks and affect both their and the city's long-run economic prospects. To a certain degree, this also happens in cities with abundant natural resources such as coal or shale gas; in the short run, the temptation to limit education efforts is high at those locations given that job opportunities for those with low-to-moderate skills are readily available.

The empirical evidence suggests that small- and medium-sized cities such as Petersburg tend to be highly specialized, have a predominantly low- to moderate-skilled population, and concentrate their activities in specific sectors, such as steel, textile, auto, shipbuilding, aircraft, pulp and paper, petrochemical, and tobacco. In contrast, bigger metropolitan areas tend to be more diversified, host firms that produce high-tech manufacturing products, and provide a greater range of global financial and business services. While dominant local firms in smaller city settings benefit mostly from the size of their own industry, bigger cities attract activities that benefit from larger concentrations of people and industries. Additionally, the academic literature suggests that a city is more likely to become specialized if, in the past, transport costs were low.

Many small- to medium-sized cities in the United States have been hurt by one or more negative economic shocks, much like Petersburg. In the most extreme instances, those cities have lost much, if not most, of the industrial base that was once the pillar of their local economy. There are, however, other cases of cities, such as Bethlehem, Pa., and Concord, N.C., that were able to reinvent themselves and overcome decades of urban decline.

So why did Petersburg, founded at a location that was well adapted for long-term economic growth at the time, later follow a path of high levels of poverty, high unemployment, and dimming economic prospects? How did other cities, subject to similar economic challenges, turn things around and become attractive places? These questions have received a lot of attention in the economics literature, but the research has not yet been able to conclusively describe the mechanisms that determine the success or failure of certain cities. History has played an important role in explaining the initial development of some cities. However, not all of them have stayed on a prosperous path. One common element of the cities that have succeeded has been their ability to attract innovative industries and talented individuals, which eventually made those locations even more successful. Despite recent advances, there is still a lot of work to be done to understand the connection between specialization, diversification, and city growth.

Prospects for Revival

Petersburg grew and prospered for nearly 300 years through trade, textiles, and tobacco but now suffers from prolonged economic decline that has been amplified through reported fiscal mismanagement. Financially, the city has seen its tax coffers strained to cover the costs of providing services. Physically, this has resulted in delayed and, in some cases ignored, maintenance of infrastructure.

Despite the difficult path Petersburg has followed in recent decades and the current signs of decline that it faces, the area retains features that may yet define a positive direction for its future. Just as improving transportation technology effectively brought the city closer to Richmond over time and drew residents and income away from the city, so too might this force contribute to Petersburg's eventual rebound.

The Peter Jones Trading Station is one of the many landmarks that reflect Petersburg’s rich historical legacy.

Petersburg's rich historical legacy is reflected in the wealth of architectural buildings in the Old Towne Historic District, adjacent to the Appomattox River. This infrastructure and location were the foundations that led to the emergence or trade and production then. In recent years, similar elements have resurrected a number of small towns in relatively close proximity to larger urban areas. Historical districts may function as the centerpiece of areas providing an array of amenities such as restaurants, entertainment, and shopping and can serve, at the same time, as the core of residential areas.

Adding to the potential for a residential-based development, the shorter commute times that hampered Petersburg's attractiveness on the jobs front could potentially support the city's viability. The proximity of the river is an added attraction.

Of course, the hurdles that must be cleared are formidable. A critical density of residential development must occur before the historical district amenities are viable. In turn, those amenities being in place would support residential development.

This chicken-and-egg situation can pose a substantial challenge and can lead to little or no development, leaving Petersburg's future uncertain. In a recent working paper, two Richmond Fed economists, Ray Owens and Pierre Sarte, with Esteban Rossi-Hansberg of Princeton University, ask whether Detroit has been in a somewhat similar position. The researchers suggest that residents of a city want to live in close proximity to one another and in sufficient numbers to generate stores and entertainment options. The paper evaluates how a specific policy instrument, a local government guarantee of residential investment, may foster the redevelopment of neighborhoods in cities like Detroit.

Under this type of policy, the city government contracts with local builders for the construction of an appropriate number of housing units in targeted neighborhoods. Such a policy, the paper shows, could generate sufficient housing and population density to make the amenities financially viable. In fact, private sales would likely end up absorbing all of the residential units, leaving none for the local government to buy — effectively making the guarantee costless to the local government. It may be that such a policy, or some other policy to jumpstart Petersburg's residential development, could help the city reverse its downward economic trend.

One thing that is clear is that regardless of the path Petersburg takes, it seems unlikely that the city will look like it did in the past. City leaders and residents should realize that any attempt to revitalize the area should be based on a realistic approach that exploits as much as possible the beauty of its historical downtown area and the river and its location near other prosperous locations. Betting the future of the city on the willingness of a couple of large firms to operate in the area may lead Petersburg to again face some of its old economic problems.

Readings

Gyourko, Joseph, Christopher Mayer, and Todd Sinai. "Superstar Cities.![]() " American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, November 2013, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 167-199.

" American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, November 2013, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 167-199.

Henderson, J. Vernon. "Cities and development." Journal of Regional Science, February 2010, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 515-540. (Article available![]() online with subscription.)

online with subscription.)

Krugman, Paul R. Geography and Trade. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991.

Owens, Raymond E., Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, and Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte. "Rethinking Detroit." National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 23146, February 2017. (A similar version of this paper is available online.)

Reed, Rowena. Combined Operations in the Civil War. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1978.

Scott, J. G. and E. A. Wyatt IV. Petersburg's Story, A History. Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson Printers, 1960.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.

As a new subscriber, you will need to confirm your request to receive email notifications from the Richmond Fed. Please click the confirm subscription link in the email to activate your request.

If you do not receive a confirmation email, check your junk or spam folder as the email may have been diverted.

You can unsubscribe at any time using the Unsubscribe link at the bottom of every email.