Following in the Family Footsteps

When children enter a parent's profession, they probably aren't doing it blindly — they may have smart economic reasons

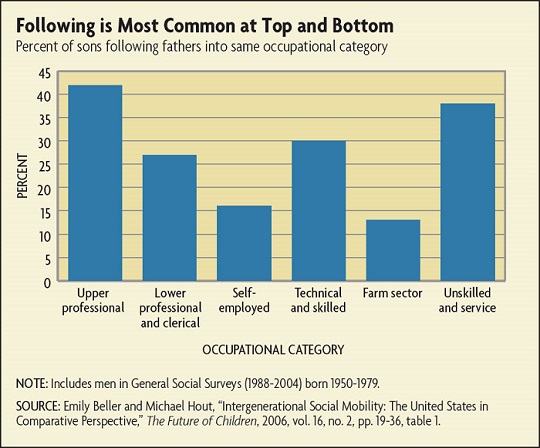

Historically, the phenomenon of children entering their parents' careers — following in their parents' footsteps — was perceived as a social ill. It was a sign that the children were trapped by barriers keeping them out of other occupations and relegating them to reliving the work lives of their parents.

"It was interpreted as a negative in the sense that it represented children not being able to escape the occupation that their parents had," says David Laband, a retired Georgia Tech economist who has studied footstep-following extensively. "It reflected what we might call occupational immobility."

But as it turns out, many of the fields in which footstep-following is relatively common are ones with lines of people clamoring to get in, including law, politics, medicine, and sports and entertainment. That's hard to square with the historical view. Is a woman who follows her mother or father into medical school, say, really doing so because it's her only alternative?

One sport among many with a lot of footstep-following competitors is auto racing. Among race drivers who drove NASCAR cup series races in 2005, almost a third were the son, brother, or father of another driver or former driver. Were Dale Earnhardt Jr. and Kyle Petty trapped by society into entering their fathers' occupation, NASCAR auto racing?

To be sure, some footstep-following workers — whether sports stars or upper-middle-class professionals — begin their careers with a head start thanks to privileged circumstances. But money, legacy admissions at elite universities, and other boons of privilege don't just help a doctor's child become a doctor: They confer advantages that help that child get in the door of any number of elite occupations, most of which don't require suffering through organic chemistry and residencies. While economic privilege confers advantages, privilege alone, researchers agree, doesn't account for the footstep-following decision.

What economists have long known is that footstep-following occurs more often than simple chance would predict and, moreover, that children following in their parents' footsteps enjoy a wage premium, on average, over those who don't. So what's going on?

Human Capital Begins at Home

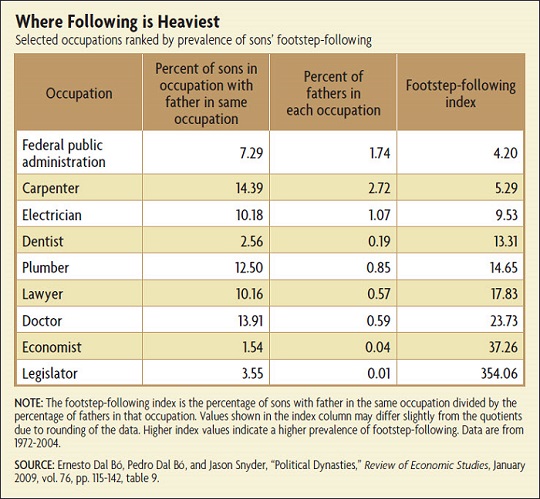

Among male attorneys, more than 10 percent have a father who is or was also an attorney, according to survey data. (See table below.) Studies going back to the 1950s have found extensive footstep-following in law. Laband, with co-author Bernard Lentz, then of Ursinus College, sought to shed light on why. They had access to data from a research effort called Project Talent, which gathered detailed information from around 400,000 high school students from 1960 to 1973, including the students' knowledge of the law (as measured by a nine-question quiz) and how much they talked with their parents about their career plans.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.