Medicine Markup

Americans pay a lot for prescription drugs. Does that mean we pay too much?

Diabetics rationing their insulin because they can't afford the full dose. Senior citizens choosing between filling their prescriptions and buying groceries. Parents hoping an expired EpiPen will still work if their child has an allergic reaction.

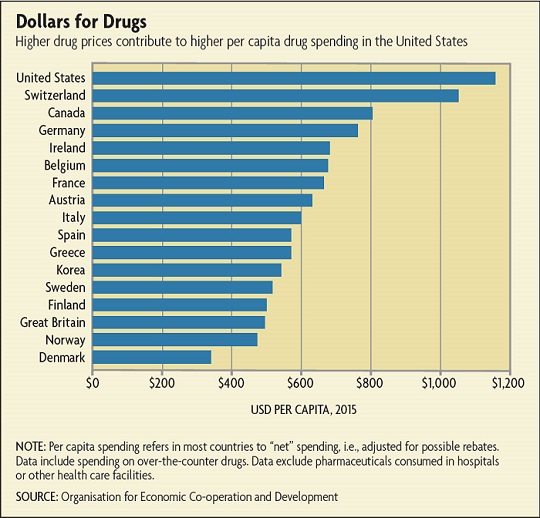

Stories about Americans unable to pay the high cost of prescription drugs are not new. But in recent years, drug prices have drawn increased attention from policymakers on both sides of the aisle, prompted by the advent of expensive new treatments for Hepatitis C, cancer, and other illnesses, as well as steep price increases for existing treatments such as EpiPens and insulin. Prices look especially high when compared to those in many other developed countries, particularly in Europe.

In theory, the lack of drug price regulation in the United States stimulates innovation: The potential for high returns is why pharmaceutical manufacturers (and their investors) are willing to fund risky and expensive research. In practice, however, there are reasons to believe that the large revenues pharmaceutical companies earn from the U.S. market reflect not just the value of the innovations the companies have provided, but also the efforts those companies have expended to circumvent competition.

There are several reasons policymakers may want to ask to what extent drug pricing leads to an efficient distribution of resources. Prescription drug spending totaled nearly $330 billion in 2016, 1.8 percent of GDP, and the government paid for more than 40 percent of it. More generally, drug spending and health expenditures overall affect both sides of the Fed mandate to support maximum employment and price stability. Health care spending totals 18 percent of GDP and health care is the third-largest employment sector. In addition, medical spending can alter the behavior and overall level of inflation. "The U.S. [pharmaceutical] system performs well when competitive forces are strong," wrote Fiona Scott Morton and Lysle Boller of Yale University in a 2017 paper. But when manufacturers can earn high profits by weakening or sidestepping competition, "the system no longer incentivizes the invention of valuable drugs. Rather, it incentivizes firms to locate regulatory niches where they are safe from competition on the merits with rivals."

Americans Pay More for Drugs

"Price" is not a straightforward concept in the pharmaceutical industry. Manufacturers sell drugs to wholesalers, who distribute them to pharmacies and mail order prescription services, who then distribute them to patients according to the reimbursement plans established by insurers and pharmacy benefit managers. At each step along the way, buyers and sellers negotiate substantial — and confidential — rebates and discounts. As a result, the published list price is generally much higher than what patients actually pay, although that is less true for patients with a high-deductible insurance plan or no health insurance at all.

Even taking those discounts into account, which researchers can do by comparing sales data to list prices, Americans pay more for many prescription drugs. Net prices in the United States for the country's 20 highest-selling drugs averaged more than twice the list prices in four other developed countries in 2015, according to research by Nancy Yu and Peter Bach of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Zachary Helms, formerly a project coordinator at the center.

A Bloomberg analysis found similar results. In 2015, the cholesterol pill Crestor cost $86 per month after discounts in the United States versus list prices of $41 in Germany, $32 in Canada, and $20 in France. Humira, which treats rheumatoid arthritis, cost $2,505 per month after discounts in the United States but listed for just $1,749 in Germany, $1,164 in Canada, and $982 in France. Partly as a result, per capita drug spending in the United States far exceeds per capita spending in other developed countries. (See chart below.)

Since 1994, the share of prescriptions filled with generic drugs has climbed from 36 percent to nearly 90 percent.

Pharmaceutical companies also have been accused of exploiting the Orphan Drug Act, a 1983 law that encourages drug manufacturers to develop treatments for rare diseases by offering tax credits and extended market exclusivity. An investigation by Kaiser Health News published in January 2017 found that one-third of the 450 orphan drug approvals granted by the FDA since 1983 were for previously approved mass-market drugs that had been reclassified with a new use, or for drugs that had received multiple orphan designations — and thus multiple incentive packages. Drug makers may also use orphan drug status to delay the entry of generic competitors. (See sidebar.) Since Kaiser published its report, the Government Accountability Office has announced it will investigate the orphan drug system, and the FDA and Congress have begun closing some loopholes.

Taking advantage of existing laws or spending money on politics may not be inherently problematic. But economists tend to be especially wary of the latter when it takes the form of rent seeking, the economic term for attempting to acquire excess profits through political means. Not only is such behavior likely to result in inefficient policies, the money spent on lobbying or campaign donations to influence regulation is money that could have been spent on productive uses — such as developing new drugs.

Between 1990 and 2016, the pharmaceutical industry donated $185 million to political candidates, political action committees, and other political groups, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics. Contributions increased from $9.1 million in the 1998 cycle to $19 million in 2000 and $21.3 million in 2002. Many observers believe the pharmaceutical industry was instrumental in adding the ban on Medicare negotiations with drug companies in the 2003 law.

Campaign contributions are dwarfed by the amount spent on lobbying, on which there are no spending restrictions. Since 2007, the pharmaceutical industry has spent about $240 million annually on lobbying; in 2009, a year of intense debate about changes to the health care system, lobbying totaled more than $270 million.

At least when it comes to politicians' rhetoric, political spending might not be having much of an effect recently; lawmakers across the political spectrum have declared their intention to lower drug prices. But while that might sound desirable from the consumer's perspective, it's far from clear that lower prices across the board would be an efficient outcome, either. "We pay too much attention to the average price level and not enough to variation across drugs," says Kyle. "Big breakthrough drugs don't get the prices that are justified, but then we pay too much for drugs with only marginal benefits. Aligning pricing with clinical benefits would create better incentives for innovation and make better use of our health care resources."

Readings

Berndt, Ernst R., Deanna Nass, Michael Kleinrock, and Murray Aitken. "Decline in Economic Returns from New Drugs Raises Questions about Sustaining Innovations."Health Affairs, February 2015, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 245-252.

DiMasi, Joseph A., Henry G. Grabowski, and Ronald W. Hansen. "Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: New Estimates of R&D Costs." Journal of Health Economics, May 2016, vol. 47, pp. 20-33. (Article available with subscription.)

Kyle, Margaret. "Are Important Innovations Rewarded? Evidence from Pharmaceutical Markets." Review of Industrial Organization, forthcoming.

Scott Morton, Fiona, and Lysle T. Boller. "Enabling Competition in Pharmaceutical Markets." Paper prepared for the Brookings Institution conference "Reining in Prescription Drug Prices," Washington, D.C., May 2, 2017.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.