Fed Eyes Central Bank Digital Currency

Policymakers are considering possible design features

Digital assets have been all the rage. Millions of Americans have invested in privately issued cryptocurrencies, whose market value surpassed $3 trillion for a while late last year. Further pushing the envelope of innovation and speculation, the prices of so-called "algorithmic" cryptocurrencies such as TerraUSD have been supported by yet other cryptocurrencies in arrangements that some observers have likened to Ponzi schemes. Meanwhile, collectors have spent billions of dollars to purchase pieces of art and other items in the form of digital "non-fungible tokens" or NFTs.

Amid this flurry of activity, policymakers around the globe are gauging possible responses to the fast-changing financial environment. In March, the Biden administration issued an executive order outlining what it called a "whole-of-government approach to addressing the risks and harnessing the potential benefits of digital assets and their underlying technology." A prominent part of the order was a call to explore the creation of a central bank digital currency, or CBDC.

The United States is far from alone in its interest in a CBDC. Several countries have already launched official CBDCs, more than a dozen others have launched pilot programs, and many more are engaged in research and development projects linked to the possible creation of CBDCs. In 2020, a group of major central banks, including the Fed, issued a joint report on foundational principles pertaining to CBDCs. And in January of this year, the Fed issued a white paper to stimulate a public discussion about the possible benefits and risks of a U.S. CBDC.

What Is a Central Bank Digital Currency?

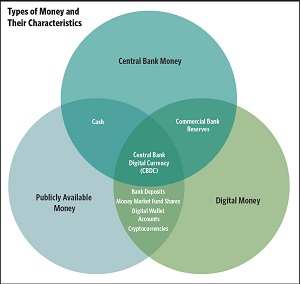

A U.S. CBDC would be a digital liability of the Fed that the public could use as a means of payment. It would constitute a third type of central bank money alongside Federal Reserve Notes — more commonly known as paper currency or cash — and commercial bank reserve balances at the Fed. A CBDC's digital form would differentiate it from cash, while its availability to the public would differentiate it from commercial bank reserves. (See figure.)

"Should the Fed Issue Digital Currency?" Economic Brief No. 21-10, March 2021.

"Payments on Digital Platforms: Resiliency, Interoperability and Welfare," Working Paper No. 21-04, February 2021.

"Technology Adoption and Leapfrogging: Racing for Mobile Payments," Working Paper No. 21-05R, Revised August 2021.

The design of a CBDC can vary greatly depending on the objectives of policymakers. One of the first design questions often raised is whether a CBDC should be account-based or token-based. A key distinction between the two systems is their identification requirements. For a traditional bank account, intermediaries establish ownership by verifying the owner's identity. For many token-like instruments, such as Federal Reserve Notes and cryptocurrencies, ownership is established by possession — the thing that needs to be verified is not the owner's identity but rather the instrument's authenticity.

The two systems can differ greatly in how they treat fraudulent and erroneous transactions. In account-based systems, providers of traditional bank and credit card accounts typically reimburse account holders after establishing that third parties have fraudulently made payments. In token-based systems, on the other hand, there is little recourse for people who have their money lost or stolen. Nor is there reliable recourse for the recipients of counterfeit crypto tokens. Much like the recipients of fake $20 bills, they may simply be out of luck.

A second, closely interrelated question is ledger design. Payments with a CBDC are, by definition, transfers of a central bank liability — transfers that must be recorded on some sort of ledger system. The ledger could be managed in a centralized manner, with a single trusted party responsible for record keeping. Alternatively, the ledger could be managed in a decentralized manner on a network of separately owned computers, with collective or "distributed" record keeping, in the manner of Bitcoin. Hybrid approaches are also possible.

A third major design issue has to do with distribution and administration. The main question here is whether a CBDC should be offered directly to the public by the central bank or through financial intermediaries, who would likely administer CBDC accounts much like trust funds on behalf of their owners.

Researchers have been hard at work exploring the technical issues raised by a CBDC. One of these efforts is Project Hamilton, an MIT/Boston Fed collaboration. Their recent Phase 1 report suggests that simple dichotomies such as token-based vs account-based and centralized vs. decentralized are only a starting point for understanding the design issues. In their view, these categorizations aren't enough to encompass "the complexity of choices in access, intermediation, institutional roles, and data retention in CBDC design." It cited the example of a digital wallet, which "can support both an account-balance view and a coin-specific view for the user regardless of how funds are stored in the database." In a similar vein, a central bank can maintain a centralized ledger while delegating much of the system's customer-facing work to private sector intermediaries, such as banks.

The Fed's White Paper

The Fed's January white paper reveals much about the Fed's views on design trade-offs. For one thing, the Fed does not view a U.S. CBDC as a replacement for cash, essentially agreeing with other major central banks that "a CBDC would need to coexist with and complement existing forms of money."

The Fed expressed reluctance to get into retail banking (a move that might require congressional authorization). Instead, the white paper favored an intermediated approach that would work through private financial institutions to take advantage of their existing systems for complying with anti-money laundering laws and Know Your Client laws.

With regard to privacy, the Fed said it wants to "strike an appropriate balance .… between safeguarding the privacy rights of consumers and affording the transparency necessary to deter criminal activity." The Fed's concerns about money laundering and terrorist finance preclude a CBDC that has Bitcoin-like anonymity. Still, the Fed stated, "Protecting consumer privacy is critical."

"The Fed is proposing a framework in which the government does not have too much direct access to personal account information but does have the capacity to get it through legal process," says Howell. "So, the government will be able to get information the same way they now get information from private institutions — either through AML [anti-money laundering] reporting or legal process. I think they're trying to keep that as a sensible division — something that people in the United States are comfortable with."

A Solution in Search of a Problem?

Fed Gov. Christopher Waller concluded an August 2021 speech with the observation, "I am left with the conclusion that a CBDC remains a solution in search of a problem." He is not alone in this sentiment, as many observers have registered skepticism that a CBDC is either necessary or sufficient to achieve the two major goals that its advocates have set for it: improving payments systems and increasing financial inclusivity.

Some say a CBDC intermediated through private financial institutions, as suggested by the Federal Reserve Board's white paper, may not offer much in the way of innovation — that it may merely overlap with current retail offerings, including traditional banking accounts and newer real-time payment services, such as Zelle. They look to other ways of improving payments.

"I think for almost all — if not all — of the policy objectives that have been advanced for a CBDC, there are less risky, more efficient alternatives to achieve those objectives," says Rob Hunter of The Clearing House. "For faster payments, those alternatives are the already functioning RTP network and the soon-to-be available FedNow network."

It is uncertain whether a CBDC would lower the costs associated with cross-border payments. "With cross-border payments, the biggest cost overlay is really in the compliance area," says Hunter. "You're talking about payments in jurisdictions that have different AML and terrorist financing frameworks. And that's really where the cost drivers are coming in. And unless a CBDC is going to ignore all those frameworks, it's not really going to solve for that."

Finally, there would be obstacles to be overcome for a CBDC to increase access for the underbanked. Nelson argues that someone who does not already have a standard bank checking account would not be more likely to open a CBDC account without some further inducement. "When you ask people why they are underbanked, the reasons they list are not having enough money to open an account or being distrustful of financial institutions," says Nelson. "These are things that don't really seem to be fixed by a CBDC. You'd have to provide subsidies to attract people who don't already have bank accounts, and that would be quite costly."

Be Prepared

Even if it is controversial whether some problems can be fixed by the introduction of a CBDC, many observers think there still are compelling reasons to conduct research into them — and about digital assets and platforms more generally. "We don't exactly know how things are going to evolve in the digital money and payments space," says Wang. "It will take great efforts to get the right regulations in place and it will take time to get the CBDC technology ready, and it will be good to prepare on both fronts."

READINGS

"Central Bank Digital Currencies: Foundational Principles and Core Features." Bank for International Settlements, October 2020.

"Money and Payments: The U.S. Dollar in the Age of Digital Transformation." Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January 2022.

"On the Road to a U.S. Central Bank Digital Currency — Challenges and Opportunities." The Clearing House, July 2021.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.