Transportation Access as a Barrier to Work

Lack of a car can be a barrier to employment, particularly for low-income individuals. According to a 2022 survey conducted by the South Carolina Department of Employment and Workforce, almost 20 percent of individuals in that state who were able to work but were not currently working cited transportation as a barrier. Many studies have shown that ownership of a car (or a truck or motorcycle) increases the probability of work, especially among welfare recipients. And low-income individuals are the least likely to own a car and therefore must rely on other means of transportation, such as public transportation, ride services, bikes, or walking to get to work.

Moreover, users of public transportation tend to have lower incomes and longer commute times. (See "Transportation and Commuting Patterns: A View from the Fifth District," Econ Focus, Second/Third Quarter 2019.) While public transportation options typically exist in larger urban areas, those options become more limited farther outside an urban center.

In addition to needing access to a car, individuals also need to be able to legally drive it. Revoking driver's licenses can create additional barriers. Some research shows that lower-income individuals and minorities are most likely to have their licenses revoked. There are, however, some potential ways to mitigate barriers to transportation, including expanding or creating new public transportation options, providing access to financial and educational resources to help people purchase cars, and overturning laws that limit people's ability to drive the cars that they do have access to.

Low Incomes and Access to Cars

The most common mode of transportation to work in the United States, by far, is to drive alone in a personal vehicle. Despite the fact that just over 95 percent of workers live in a household with access to at least one car, and driving alone is how more than two-thirds of the workers in the U.S. get to their place of employment, there are considerable differences in access to car ownership across the income spectrum.

There are, however, some potential ways to mitigate barriers to transportation, including expanding or creating new public transportation options, providing access to financial and educational resources to help people purchase cars, and overturning laws that limit people's ability to drive the cars that they do have access to.

Car ownership may seem almost universal, but it isn't — far from it. In every state in the Fifth District and in the District of Columbia, car ownership declines with income. (See chart.) The share of people with access to at least one car ranges from about 40 percent among very low-income households in D.C. to 99 percent among high-income households in every other state. And the gap in car access between the lowest and highest income levels can be significant. In D.C., only 40 percent of low-income workers have access compared to over 80 percent of high-income workers. Elsewhere in the Fifth District, the share for low-income workers hovers around 80 percent while the same share for high-income workers is nearly 100 percent.

In D.C., car ownership rates are notably lower across all income levels, likely due to two factors: its broad public transportation system and the fact that higher taxes, registration fees, and parking fees make owning a car there more expensive.

Regardless of income, people not working are less likely to have access to a car. In every state in the Fifth District, access to at least one car for individuals who were unemployed or not in the labor force was around 4 to 7 percentage points lower than for those who were working. In D.C., the difference in rates compared to employed individuals was a staggering 17 percentage points lower for those unemployed and 13 percentage points for those not in the labor force. Those individuals at the lowest levels of income and not working are far less likely to have access to a car. (See charts.)

Is Access to a Car More Important in Rural Areas?

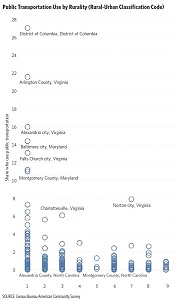

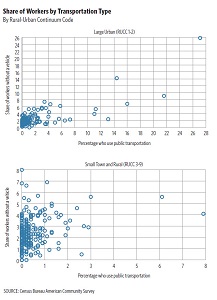

Not having access to a car in a place where other transportation options are more readily available is very different from not having a car in an area with more limited options. County-level data from the Census Bureau's American Community Survey show that while some of the lowest rates of car access do occur in urban areas of the Fifth District, there are several rural counties that have similarly low rates, have high levels of poverty, and have fewer transportation options than their urban counterparts.

For example, among the top 10 counties in the district with the lowest ownership rates are Dillon County, S.C.; Washington County, N.C.; and Northumberland County, Va. All of these counties are classified as rural according to the Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. (The RUCC is a classification system based on the size of a county's urban population and proximity to metro areas, with 1 being most urban and 9 being most rural.) Additionally, all of them have median incomes below and poverty rates above their respective state averages.

In Dillon County, for example, 8 percent of workers don't have access to a car; this is the fourth highest rate in the district after the District of Columbia, Baltimore city, and Arlington, Va. Dillon has a large low-income population with a median income in 2021 that was about 37 percent lower than the state median and the poverty rate was 26 percent — much higher than the state rate of 14 percent. Moreover, the 8 percent figure is for those who are working and therefore doesn't capture the people who are likely unable to work because of a lack of transportation.

Several urban counties also have low rates of car access and high concentrations of low-income population, but they also have public transportation options available to them. For example, Richmond and Norfolk cities in Virginia tend to be poorer with median incomes below and poverty rates above the comparative state rates, but their public transportation systems offer a variety of routes at subsidized costs.

All of these data suggest that individuals at the lowest levels of income and people in densely urbanized counties with public transportation systems are less likely to own a car. Those two facts can be hard to disentangle, however. Take the city of Norfolk, for example, which is an area with a public bus system, but also one with lower incomes and high poverty rates, making it difficult to know which issue is behind the city's low car ownership.

Rural Workers Use Public Transit More

Similarly, in the RUCC 7 category, the outlier is Norton city, Va., which is a small city in the Appalachian region of southwest Virginia. Citizens of Norton have access to the Mountain Empire Transit system, which offers transportation services across the counties of Lee, Scott, Wise, and Norton.

The Challenge of Driver's License Suspensions

Another factor that has received some attention by researchers and by government officials is the suspension of driver's licenses for reasons other than traffic offenses. In North Carolina, for example, a driver's license can be suspended for nonpayment of court fees and for failing to appear before the court for traffic offenses. In a 2019 Duke University School of Law paper, authors William Crozier and Brandon Garrett looked at court data from 1986 to 2018 and found that there were 1.2 million driver's licenses suspended for these reasons, representing approximately 15 percent of the state's drivers.

The report also found that driver's license suspensions were disproportionately imposed on Black and Hispanic drivers. About 33 percent of those with failure-to-appear suspensions were Black and 24 percent were Hispanic, while 35 percent were White. For unpaid fee suspensions, 47 percent of drivers with such suspensions were Black, 11 percent were Hispanic, and 37 percent were White. For context, in the same year, the North Carolina driving population was 21 percent Black, 8 percent Hispanic, and 65 percent White.

Virginia had a similar policy until 2020, when a law was enacted to end the practice of suspending licenses for nonpayment of fines and court fees. Additionally, the law retroactively reinstated any licenses of Virginians who had previously had their licenses suspended for those reasons, which was an estimated 900,000 people, accounting for two-thirds of all suspended licenses in the commonwealth.

West Virginia also repealed a similar law in 2020, and Maryland amended its law to stop suspending licenses for unpaid traffic fines. South Carolina continues to suspend licenses for nonpayment of fees. There is limited research on the effect of these laws, but having a revoked license clearly affects a person's ability to use his or her car to travel to work.

Remote Work: A Red Herring

In principle, remote work could provide an opportunity for low-income individuals to work without car ownership. A 2023 report by Payscale showed that the amount of work being done from home all or most of the time rose from 10 percent in 2019 to 28 percent in 2023. In reality, however, remote jobs tend to be in higher-wage sectors of professional business services like computer, mathematical, financial, and legal professions. Within lower-wage industries such as food and accommodation services, 75 percent of the jobs are performed in person.

This pattern is reflected in income figures. The average annual income from an in-person food service job is just over $35,000, whereas a food service job that could be done remotely has an average income of over $50,000 a year. Similarly, in the retail sector, where 70 percent of jobs are done in person, the wage gap is even higher: around $35,000 for in-person jobs and almost $68,000 for a remote job. In many industries, lower-skill and lower-paid jobs remain largely in person and thus the switch to remote work in many occupations did little to change the commuting needs of lower-income workers.

Innovative Approaches for the Underserved

One option that is being tried in rural areas is an on-demand public transportation system without traditional routes, also known as microtransit. These systems typically rely on shuttle vans. The Mountain Empire Transit (METGo) system in rural southwest Virginia, mentioned earlier, is an example. That system was started in 2021 along with the Bay Transit Express system in Gloucester, Va. Both systems received a combined $160,000 innovation grant from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) to launch these services.

When METGo launched, the service cost was 75 cents for seniors and children under 17 and $1.50 for everyone else; more recently, METGo received an additional grant from the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation that allowed it to offer the service free of charge. The system also received a grant to expand service to Mountain Empire Community College and an industrial park in Duffield to help transport citizens to education and job centers. According to an article published in August by the Virginia Mercury, since its launch in June 2021, METGo has provided over 76,000 rides to residents of Norton city and the counties of Lee, Scott, and Wise.

In many industries, lower-skill and lower-paid jobs remain largely in person and thus the switch to remote work in many occupations did little to change the commuting needs of lower-income workers.

As another example of a rural public transportation initiative, Bay Transit Express has been providing shuttle services in the Northern Neck region of Virginia since 1996, but the FTA grant allowed them to replace two fixed routes in Gloucester and instead allow citizens to book on-demand and point-to-point rides in the service area through an app or over the phone. According to the Virginia Mercury, ridership on the Bay Transit Express system increased over 200 percent over the fixed routes that it replaced.

There have also been recent investments in urban transit options. For example, during the pandemic, Richmond city and Chesterfield County, Va., which jointly own the GRTC transit system, made bus trips free for all riders. This has been extended several times, and bus trips will remain free at least through June of 2025 because of a grant.

In addition to improving public transportation options, there are programs from nonprofits and community development financial institutions that help low-income families access financing to purchase a car. One example of this is the Responsible Rides program in Roanoke, Va. This partnership between Freedom First bank, several nonprofits in the area, and car dealerships offers low-interest loans along with financial and car maintenance classes to educate borrowers on budgeting for the ongoing costs of owning a car.

Other entities, such as People Inc., offer personal loans to purchase cars as one of many services aimed at helping economically disadvantaged people in their service areas of rural southwest and northwest Virginia. In 2022, People Inc. loaned over $400,000 to 104 people to help them purchase cars and cover household expenses.

Conclusion

For most people, access to work requires transportation. The vast majority of Americans use a personal vehicle to get to work, but not everyone has access to one. The difficulty getting to work without a car is particularly challenging in rural areas where public transportation options are more limited. Some of the ways that these challenges have been addressed are public and private investments in subsidizing the cost of public transportation, creating point-to-point systems rather than traditional fixed routes, repealing or limiting driver's license suspension laws, and providing access to loans and educational resources to individuals to help purchase and maintain a car.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.