Transportation and Commuting Patterns: A View from the Fifth District

The transportation system is a key component of the economic performance of regions. An important role of the urban transportation system is to facilitate commuting between homes and jobs. At the national level, in 2017 commutes represented on average about a quarter of all annual vehicle trips per household. (The shares of trips that were shopping trips, recreational and social trips, and other trips for personal and family reasons were all about the same.) Economists have more data on commuters and their commutes than is commonly realized — and it's relevant to many economic questions.

National Commuting Data

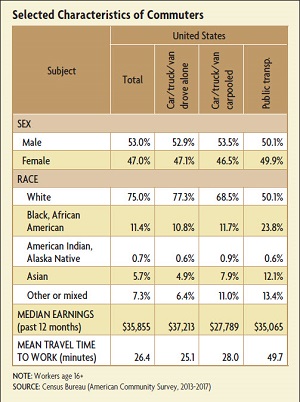

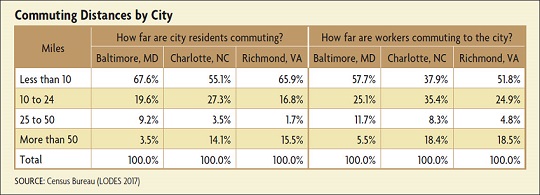

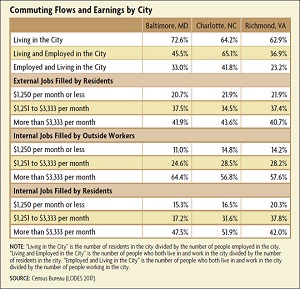

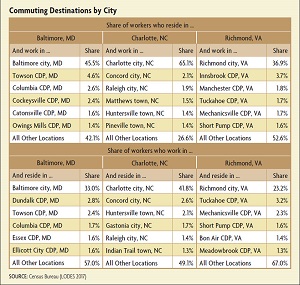

The commuting and workplace data of the American Community Survey (ACS) and the Longitudinal Employer- Household Dynamics Origin-Destination Employment Statistics (LODES) are the main two sources usually considered to examine home-to-work flows. These databases, both produced by the Census Bureau, offer different but complementary information. The ACS commuting database contains information on individuals' residence and work locations, the mode of transportation, the duration of the trip, the time of the day commuters leave home for work, and the number of car, truck, or van riders. It also conveys this information according to different demographic characteristics. The LODES database describes jobs by workplace and residence location, in addition to job, employer, and worker characteristics; these include industry type, firm size, firm age, average monthly earnings, sex, race, ethnicity, and educational attainment, among others.

"Getting Unstuck," Econ Focus, Fourth Quarter 2015.

"Responding to Urban Decline," Economic Brief No. 17-07, July 2017

Given the durability of the transportation infrastructure, policies aimed at shaping the performance of the transportation system will have long-term implications.

Consider the process of suburbanization observed during the 1950s through the 1970s. This process is usually attributed to the interaction of three forces: a growing population, rising incomes, and falling commuting costs. The interaction of these forces would naturally lead to urban growth. But specialists such as Jan Brueckner of the University of California, Irvine believe that the failure to correct for the existence of different market imperfections may have also contributed to an excessive urban expansion, commonly referred to as urban sprawl. Distortions may arise, for instance, because commuters do not internalize the social costs of congestion when they drive on freeways or because developers, under traditional financing mechanisms, do not bear the burden of the increased infrastructure costs associated with new developments. Brueckner suggests that development taxes, congestion tolls levied on commuters, and other policies aimed at increasing urban densification may partially address some of these issues.

In fact, most economists tend to agree that the best way to reduce congestion is through congestion tolls. Yet only a few cities in the world (such as Stockholm, London, and Singapore) have implemented this policy. In general, this policy lacks political support, and other alternatives, such as taxes on gasoline, are more frequently used instead. The problem with gasoline taxes is that even though they do increase the cost of using the road, they do not necessarily alleviate congestion since drivers pay the same amount at congested and uncongested hours.

Other price-based mechanisms aimed at reducing traffic congestion involve changing the customary agreements between employers and employees. One example is the reimbursement of parking charges. Typically, workers pay for parking fees and employers would raise their wages accordingly. Under the revised approach, however, workers would be allowed to pocket the money from higher wages and take public transit to work rather than pay for parking fees.

Political reasons may also explain the implementation of less desirable and sometimes unproductive transportation policies. Some of these practices include the failure to adopt congestion pricing, a disproportionate emphasis on new road construction rather than maintaining existing infrastructure, the provision of free parking in congested cities, an overinvestment in lower-density infrastructure and underinvestment in higher-density infrastructure, the insufficient reliance on user fees, and the excessive reliance on funding from the national level, even for highly local projects.

Innovations

A number of innovations have been taking place recently in the transportation sector, and these changes are reshaping the way residents and workers interact in the job market. Examples include the growing role of ride-sourcing private transport services, such as Uber and Lyft, and the possibility to telecommute.

On-demand transport services allow a more efficient use of the existing stock of vehicles. By combining information technology with a potential large supply of vehicles and a flexible pricing mechanism, ride-sourcing services allow more efficient matching between passengers and drivers, resulting in higher levels of mobility and accessibility. Some empirical research indicates that on-demand services can improve the productivity of vehicles by about 30 to 50 percent relative to traditional taxi services. These could eventually improve congestion in high-density areas if fewer vehicles are required to satisfy similar mobility needs. Moreover, as more individuals rely on this system, fewer parking spaces would be required in central urban areas, reducing traffic caused by cars looking for vacant parking spots and allowing the allocation of this space for more productive alternatives. There is some evidence, however, that ride-sourcing services could generate more congestion in some cities. The reason is that not only have ride-sourcing services drawn commuters off trains and buses, they have also contributed to the increase in the number of waiting drivers with empty seats.

According to the American Time Use Survey, the share of workers doing some or all of their work at home was approximately 24 percent in 2018, growing from 19 percent in 2003. Workers in managerial and professional occupations were more likely than workers in other occupations to do some or all of their work at home. The basic theoretical framework used by urban economists to study location decisions by workers and firms would suggest that the rise in telecommuting should cause cities to spread out and become less dense in the center. The impact of telecommuting on the economy could, as a result, be ambiguous: While telecommuting reduces traffic congestion (and traffic pollution), it also reduces the beneficial impact of agglomeration economies on workers' productivity.

Other innovations, such as driverless cars, will likely also affect the way people commute. Their impact on the transportation system and commuting behavior is, however, unclear. The main challenge faced by policymakers is that due to the nature and underlying characteristics of the transportation system, investment and policy decisions in this area will have long-lasting effects on everyone's lives.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.