Do Budget Deficits Matter?

Some economists and policymakers have argued for increasing public spending. What might that mean for inflation and monetary policy?

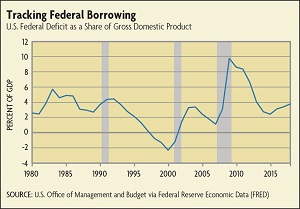

Whenever politicians propose a new project, a common question from opponents is: How are you going to pay for that? According to the standard view of government finance, any shortfall in tax revenue relative to expenses must be made up by borrowing. Over the last decade, the United States has borrowed a lot: Federal debt as a share of GDP is currently 79 percent, its highest level since World War II ended, and most forecasters predict that the debt will reach previously unseen heights over the coming decades. Annual deficits are set to exceed $1 trillion very soon, according to the Congressional Budget Office. While that would be a record in dollar terms, deficits as a share of GDP are still within historical norms for now. (See chart.)

"Unsustainable Fiscal Policy: Implications for Monetary Policy," 2011 Annual Report.

"The Benefits of Commitment to a Currency Peg: Aggregate Lessons from the Regional Effects of the 1896 U.S. Presidential Election," Working Paper No. 13-18R, November 2013 (revised January 2019).

The government's budget has sometimes been compared to a household budget. In order to make room for something new, the government either needs to get rid of some existing spending or bring in new revenue.

But economists have long recognized that there are some important differences between the budgets of households and those of nations. Households must repay what they owe over their finite lifetimes. This places limits on how much they can repay and, thus, on how much creditors are willing to lend them.

In contrast, a nation-state's lifespan has no clear upper bound. While governments must repay what they owe over the long run, for a nation with a stable system of government, the long run could be far, far in the future. In the meantime, the government only needs to make interest payments on its debt to satisfy bondholders, which it can do without raising tax rates as long as the economy is growing at a faster rate than interest is accumulating on the debt (as Summers and Blanchard have argued).

But the type of debt a government issues affects how much it can borrow. For much of history, governments tied their currency to some commodity, most commonly gold or silver. Any time the government issued debt denominated in its commodity-backed currency, it was in effect pledging to pay bondholders some real resources in the future. If bondholders decided they wanted gold instead of dollars when redeeming Treasury securities, for example, the government had to supply the gold from its reserves or raise taxes to purchase the gold needed to pay bondholders.

Today, of course, the dollar is no longer tied to gold. President Roosevelt ended the gold standard with respect to private citizens in 1934, and President Nixon did so with respect to foreign governments in 1971. Most U.S. debt today represents a nominal claim to some number of dollars in the future rather than a claim to a commodity like gold. (The U.S. Treasury does also issue debt that is indexed to inflation. But these inflation-indexed bonds make up only about 9 percent of outstanding federal debt held by the public.) Some economists have argued that this change means the government does not face a budget constraint in the same way it did under the gold standard.

"If we are talking about nominal debt, it is not a constraint. It's just an equilibrium condition that determines what the value of debt is," says Eric Leeper of the University of Virginia.

Leeper is one of a handful of macroeconomists who have advanced a theory that the government's fiscal behavior ultimately drives the value of debt and money more generally. According to this theory, prices are equal to the ratio of current nominal debt relative to the expected present value of future surpluses. If the government issues more debt but promises to repay it with higher taxes or reduced spending in the future, then prices will remain unchanged. But if the government issues new debt and makes no commitment to repayment, then prices will go up as people seek to exchange debt (including currency, another kind of government liability) for other goods.

"A constraint means that if you sell one more dollar of debt, then you have to raise taxes," explains Leeper. "But if it's nominal debt, then the value of that debt can adjust to be consistent with whatever taxes are currently in place."

John Cochrane of the Hoover Institution has used the example of corporate stock to make a similar argument. At a simplified level, the value of a company's shares are proportional to the company's expected future earnings. If the company doubles the amount of its shares without changing expectations about its future profitability, such as through a stock split, share prices will fall by half. Likewise, he argued, if the government issues more debt with no change in expected future revenues, the value of the debt, and the value of currency in general, will fall.

Adopting Constraints

In order to prevent inflationary spending, modern governments have adopted commitment devices to help ensure that public spending remains roughly balanced over the long run. One way of making such a commitment is assigning an independent central bank the responsibility of maintaining price stability.

In the United States, the Fed steers long-run inflation via monetary policy. While macroeconomists and monetary policymakers recognize that there are many factors that can influence the level of prices over the short and long haul, they largely agree that monetary policy has the ability to influence long-run inflation independent of other factors in the economy.

But according to the theory proposed by Leeper and Cochrane, monetary policy can only steer inflation as long as fiscal policy keeps the ratio of current debt and expected future surpluses constant. In other words, as long as the debt is viewed as sustainable, the Fed can use monetary policy to guide inflation toward its 2 percent target. But if fiscal policy spends beyond what markets view as sustainable in the long run, prices and interest rates may adjust in ways that the Fed cannot fully control.

By assigning the Fed independent responsibility for maintaining price stability through monetary policy, the government has in effect committed to conducting fiscal policy in a way that markets view as sustainable. This is similar to the commitment under the gold standard, where the government pledged to offset any increase in debt with an increase in gold reserves in the future. Neither commitment is fully binding, since governments can and have set aside both pledges.

It is also theoretically possible for fiscal policy to set both spending and inflation targets. A relatively new school of thought known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has argued that U.S. government borrowing shouldn't be constrained by self-imposed debt limits or future revenue. Rather, the primary consideration should be whether or not that spending will be inflationary, which MMT says has nothing to do with the government's budget.

"The government could always issue more debt," says L. Randall Wray of the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, one of the chief proponents of MMT.

In order to finance spending, MMT holds that the government could simply issue more short-term debt or have the central bank create new reserves. If there are not enough resources for the projects the government is trying to undertake, Wray says such spending will produce inflation. The government would then have to decide whether to accept higher inflation, cut back on spending, or attempt to constrain inflation in other ways. These could include wage and price controls or tax hikes to reduce private consumption of resources, says Wray. But he and other advocates of MMT are optimistic such steps wouldn't be necessary.

"I can understand the fear that if politicians knew that the federal government does not face an external financial constraint, then they would try to spend too much,"says Wray. "But I don't think there is any evidence for that."

But critics argue that removing restrictions on fiscal policy, such as borrowing limits or an independent central bank, has historically led to an inflationary increase in spending in other countries — sometimes spectacularly so.

Cautionary Tales

In a recent working paper, Sebastian Edwards of the University of California, Los Angeles argued that fiscal expansions similar to what MMT calls for have already been tried in various Latin American countries, such as Chile, Peru, Argentina, and Venezuela. In each case, Edwards says that the government increased spending on new social programs by issuing more debt and through easy money policies implemented by the central bank.

"It resulted in huge, awful crises," says Edwards. He found that the experiments generally started off successfully, but eventually bottlenecks began to appear, leading to inflation. Once inflation pressures emerged, they proved difficult to stop.

"When inflation takes over, people ditch the domes-tic money. They don't want to hold it," says Edwards. "Domestic money becomes a hot potato, and people use foreign exchange, IOUs, or something else as money."

A native of Chile, Edwards experienced this firsthand. Following an expansion of public sector spending in the early 1970s, Chile's annual inflation rate grew to more than 500 percent in 1973. By comparison, annual inflation in the United States during the Great Inflation peaked at just shy of 15 percent in 1980 and still generated substantial economic disruption.

Edwards notes that, like advocates of MMT, policymakers in Chile and other Latin American countries voiced opposition to excess inflation prior to embarking on fiscal expansion. Once inflation pressures emerged, they implemented wage and price controls and raised taxes in attempts to contain rising prices, but those measures were unsuccessful. Once policymakers removed constraints on issuing debt and currency, it became difficult to maintain a stable value for money.

An oft-cited 1982 article by Nobel Prize-winning economist Thomas Sargent of New York University provides more examples. Sargent examined the inflation experiences of Hungary, Austria, Poland, and Germany after World War I. Each country confronted economic disruptions and significant debts in the aftermath of the war. Their governments responded by issuing new debt paid for by printing money. The resulting hyperinflations ended only after the governments implemented changes to balance their budgets and established independent central banks that were prohibited from monetizing future debt. Once those commitments were in place, Sargent found that inflation ended abruptly despite the fact that the money supply in each country continued to expand.

"It was not simply the increasing quantity of central bank notes that caused the hyperinflation," Sargent wrote. "Rather, it was the growth of fiat currency which was unbacked, or backed only by government bills, which there never was a prospect to retire through taxation."

Wray argues that the episodes in postwar Europe and in Latin America don't apply to MMT's prescriptions because the debts faced by those countries were not denominated in their own currencies. Germany's debts in the Weimer Republic were tied to gold and Argentina's debts were denominated in dollars, for example, imposing real constraints on their ability to repay that the United States doesn't face.

Still, in the view of mainstream macroeconomists, such episodes suggest that when spending becomes disconnected from expectations about future revenues, inflation follows, regardless of the type of debt.

Spending More

To be sure, large fiscal expansions don't need to result in inflation. Many economists have pointed to the case of Japan, which has a debt-to-GDP ratio surpassing 200 percent but has experienced very little inflation over the last two decades. But while Japan has engaged in substantial fiscal expansion designed to boost its economy, it has also increased its consumption tax at the same time. This signals that spending increases are backed (at least in part) by future revenue surpluses. Indeed, when asked if Japan's policies served as an example of MMT's prescriptions, Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda argued that they didn't because the Japanese government "believes it's important to restore fiscal health and make fiscal policy sustainable."

There also may be times when generating inflation by committing to being "fiscally irresponsible" can be useful. In a paper with Margaret Jacobson of Indiana University and Bruce Preston of the University of Melbourne, Leeper examined President Franklin Roosevelt's response to the Great Depression. Starting in 1933, Roosevelt took the United States off the gold standard and ran "emergency" government deficits that he pledged not to repay until after the economy had recovered. This "unbacked" fiscal expansion boosted economic activity and inflation at a time when the United States was experiencing deflation. But Leeper acknowledges that pulling off something similar today would be difficult.

"Roosevelt had to get fiscal expectations anchored in the right way," he says. "During the Great Recession, Obama also enacted a fiscal stimulus, but within a week after the package passed, he was promising to raise surpluses and reduce the deficit. And that's because the politics have changed."

Even if modern-day policymakers succeeded in changing the public's expectations about fiscal policy, those expectations may be difficult to change back if things don't work out as planned. That may be why many governments have chosen to signal their intentions to balance budgets in the long run and charged independent central banks with keeping inflation steady.

"What the episodes in Latin America showed is that it is very difficult to fine-tune or stop the inflation process," says Edwards. "Now, that isn't a universal law like gravity, but the evidence tells us that we should be careful."

Readings

Blanchard, Olivier. "Public Debt: Fiscal and Welfare Costs in a Time of Low Interest Rates." Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief No. 19-2, February 2019.

Edwards, Sebastian. "Modern Monetary Theory: Cautionary Tales from Latin America." Hoover Institution Economics Working Paper No. 19106, April 25, 2019.

Jacobson, Margaret M., Eric M. Leeper, and Bruce Preston. "Recovery of 1933." National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 25629, March 2019. (Paper available with subscription.)

Sargent, Thomas J. "The Ends of Four Big Inflations." In Robert E. Hall (ed.), Inflation: Causes and Effects. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982. (Chapter available with subscription.)

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.