Loan-Delinquency Projections for COVID-19

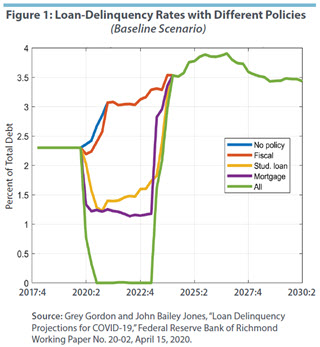

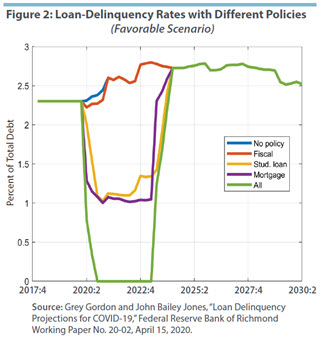

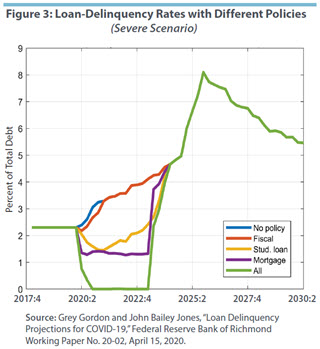

The authors forecast the effects of COVID-19 on loan-delinquency rates under three scenarios for unemployment and house-price movements. Absent policy interventions, the model predicts peak loan-delinquency rates of 2.8 percent in the favorable scenario, 8.1 percent in the severe scenario, and 3.9 percent in the baseline scenario. The greatest reductions in delinquency are achieved through home mortgage forbearance and student loan forbearance, with fiscal transfers playing a smaller role.

A key concern facing fiscal and monetary policymakers is the extent to which the sharp decline in economic activity stemming from the coronavirus pandemic will affect consumer debt payments. In a recent working paper, two authors of this Economic Brief (Gordon and Jones) used data from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) to project the incidence of loan delinquency or default in the near future.1

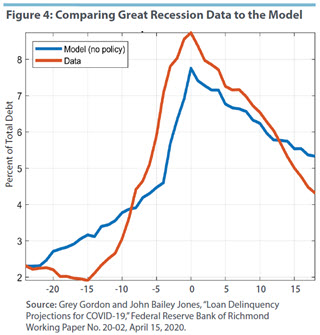

To make these projections, Gordon and Jones assumed that delinquency or default occurs when either of two financial ratios — the debt service-to-income (DSY) ratio and the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio — exceeds certain thresholds. They determined these thresholds by matching 2019 delinquency rates on home mortgage, credit card, and student loan debt and then simulated forward the DSY and LTV ratios for each SCF household under different unemployment and house-price scenarios. Using this methodology, they also assessed how well various policy proposals — fiscal transfers, student loan forbearance, and home mortgage forbearance — would mitigate increases in delinquency and default (D-D). While these calculations are not a perfect substitute for a complete economic model, they should provide reasonable first-pass estimates.

The authors considered three scenarios for the unemployment and house-price shocks: a favorable case, a severe case, and an intermediate case (the baseline).2 In the absence of policy interventions, they found that:

- When both shocks follow their baseline trajectories, the D-D rate (measured as the fraction of debt that is ninety-plus days delinquent) rises from 2.3 percent in 2019 to 3.1 percent in 2021 and peaks at 3.9 percent in 2025. The delayed peak is due to persistence in house-price decline. Total write-offs end up being $580 billion.

- When both shocks follow their most favorable trajectories, the D-D rate rises to 2.6 percent in 2021 and peaks at 2.8 percent in 2022. Total write-offs end up being $420 billion.

- When both shocks follow their worst-case trajectories, the D-D rate rises to 3.5 percent in 2021 and peaks at 8.1 percent in late 2025. Total write-offs end up being $1.1 trillion.

The three policy interventions the authors analyzed begin in the second quarter of 2020 and last for at most three years. Among the three policies they consider, the greatest reduction in the D-D rate is achieved by home mortgage forbearance, then by student loan forbearance, and lastly by fiscal transfers. With all three policies in place, like they currently are under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) act, D-D rates and write-offs fall below their 2019 levels in the near term.

Families were included in the sample if their incomes were at least $10,000 and their debts (credit card, student loans, home mortgages) totaled at least $1,000. Households older than sixty-five were dropped because they do not have much debt and are unlikely to be affected by changes in the aggregate unemployment rates. With these restrictions, the initial sample of 31,240 families dropped to 15,009. The Survey of Consumer Finances is available online.

For details on each scenario, see Grey Gordon and John Bailey Jones, "Loan Delinquency Projections for COVID-19," Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper No. 20-02, April 15, 2020.

In the absence of loan forbearance, interest rates were held fixed throughout the authors' projections. They therefore do not account for the possibility that interest rates will rise as the economy recovers from the pandemic. Most home mortgages and student loans are fixed-rate, implying that changes in interest rates only affect new borrowers. Gordon and Jones explored the consequences of raising the nominal credit card rate by 3 percentage points annually at different dates. Because credit card debt is a small component of total debt, they found extremely limited effects.

For details on each scenario, see Gordon and Jones, 2020.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.