Partisan Conflict in the U.S. and Potential Impacts on the Economy

Partisan conflict is not new, either in American politics or elsewhere. For economists, politics per se is not of central interest, but its implications for economic activity are. The more specific step we take in this article is to relay how partisan legislative disagreement has evolved and how that may affect the economy. Of particular interest are the effects on how businesses delay hiring and investment when facing high policy uncertainty. We will focus on fiscal policy since it, unlike monetary policy, must be negotiated in legislative settings. We will also concentrate attention here on the U.S. given its economic importance and because data and analyses are available to draw upon, even though our aim remains more general: to connect legislative disagreement to economic outcomes and policies in any major economy.

Diverging Agendas: A Polarized Congress

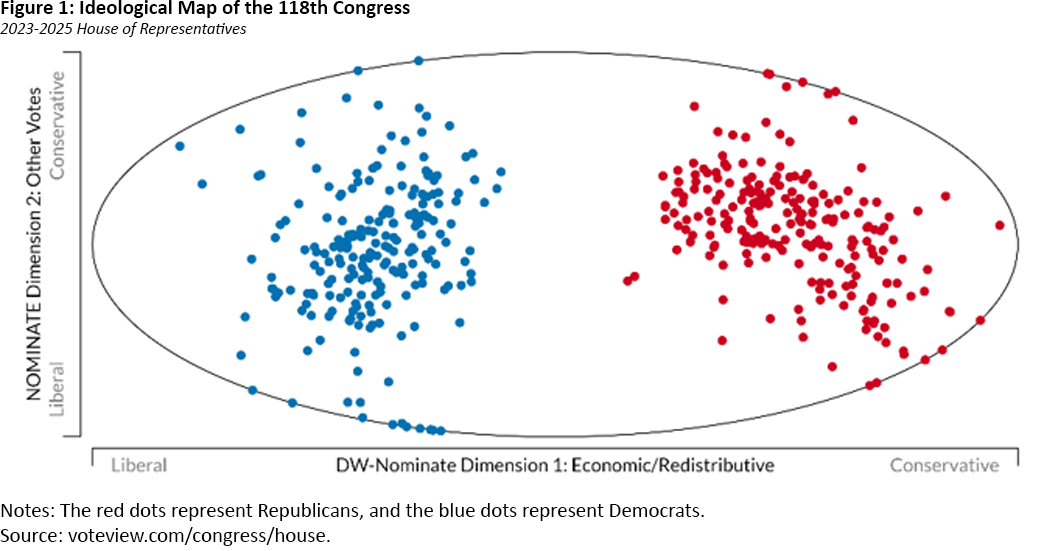

For the U.S., quantitative studies of partisan disagreement have robustly documented differences in roll-call voting behavior in Congress. Using a statistical technique that assigns each legislator a score on a liberal-conservative scale based on their voting patterns, Voteview estimates the ideological positions of individual legislators along two dimensions: economic policy/redistribution and "other." The scores range from -1 (most liberal) to +1 (most conservative), with 0 representing the midpoint. The positions of members of the House of Representatives in the 118th Congress (2023-2025) are illustrated in Figure 1.

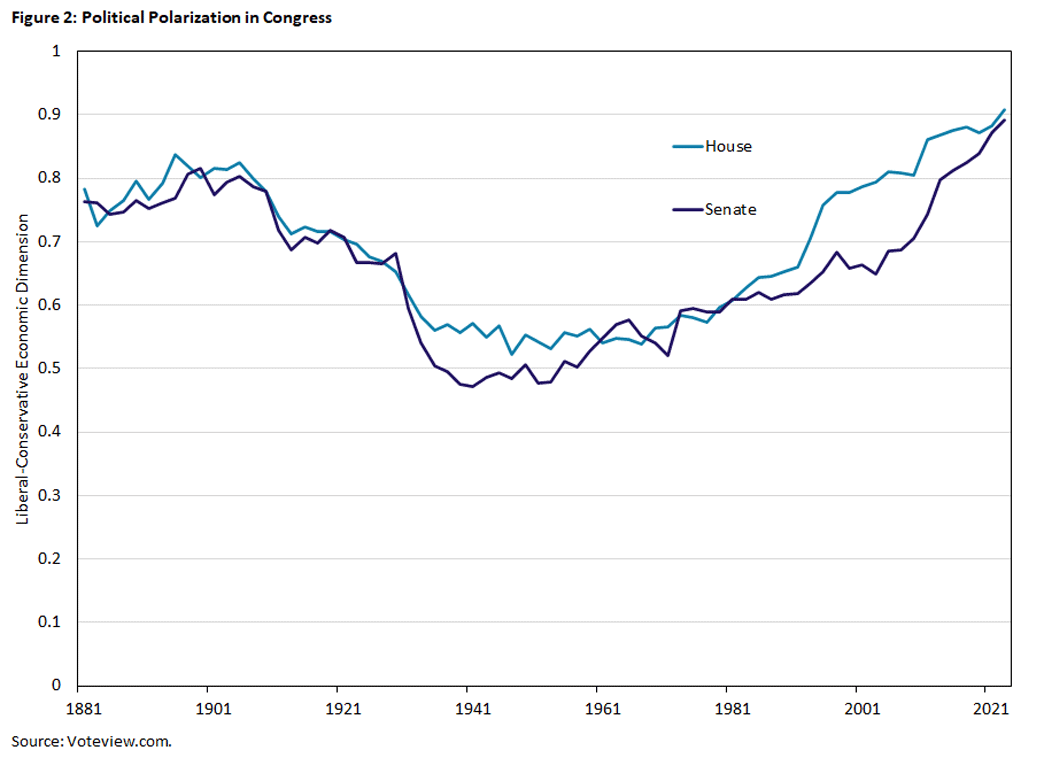

We can see that legislators' views are clustered within a party but are far apart across parties, indicating high polarization. Polarization can be measured by computing the difference in means of the two parties' ideological positions, and this measure is shown in Figure 2 below. A greater value indicates a larger degree of polarization.

Polarization is, thus, not a new phenomenon in the U.S. As Figure 2 shows, polarization in the House and Senate has been present for decades, with minimum values reached between World War I and World War II and persisting into the 1950s.

However, the 1970s marked a significant turning point, with polarization increasing substantially. In the years since, the trend has continued. The result is that the ideological gap between the two parties is now at its widest in 60 years.

Political Polarization and Partisan Conflict

While polarization is a necessary condition for partisan conflict, it is not sufficient. This is because the ability of political parties to influence policy is determined by who controls the government. In the U.S. political system — where power is divided among the executive branch and both legs of the legislative branch — determining which party has actual control can be tricky.

De-facto control depends on factors such as the leader's (here, the president) party affiliation, the party with the majority of seats in the legislature (here, the House and the Senate) and the perceived importance of the policy issue at hand. Adding to the complexity is the potential for significant disagreements even among politicians of the same party, as we have seen with southern Democrats voting closer to center Republicans than to their counterparts from the northeast.

As someone interested in measuring disagreement in political decision-making and then understanding its macroeconomic implications, I developed the Partisan Conflict Index (PCI) in my 2018 paper "Partisan Conflict and Private Investment."1 The index aims to quantify effective partisan conflict by looking at the percentage of news articles that highlight political disagreements among U.S. politicians. This approach assumes that disagreement only matters when it has a "bite" in policymaking, significant enough to be worth mentioning in the news.

To better understand this, let's take a closer look at the PCI by analyzing a real-life example: the American Rescue Plan. In early 2021, there was a $1.9 trillion package proposed of post-pandemic fiscal policies. Despite having no Republican support, Democrats easily passed the policy as they held the majority in the House and Senate.

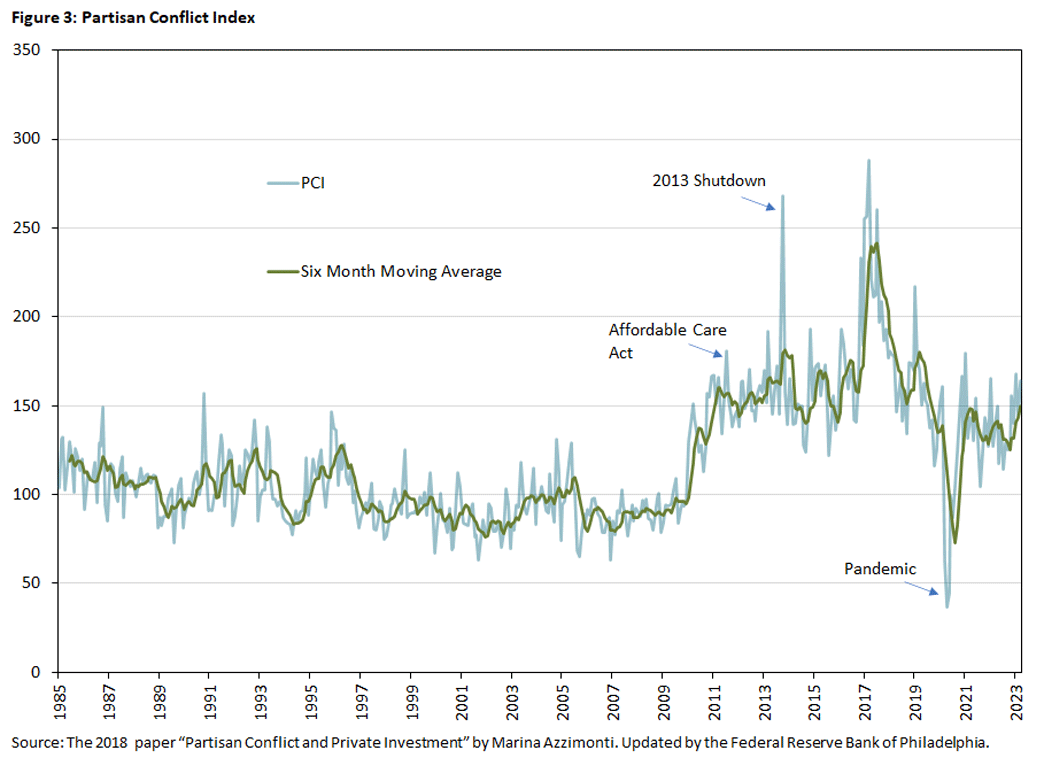

While there were many news articles covering the details of the plan itself, there were surprisingly few highlighting partisan disagreements. This is an interesting case where effective partisan conflict (at least according to our media-based measure) remained relatively low despite both parties being highly polarized about a salient piece of legislation. This is reflected in Figure 3, which depicts the evolution of disagreement (partisan conflict) between 1985 and 2023.

The figure shows that the PCI has been relatively constant from 1985 until the Great Recession in 2007. At that point, the PCI started to rise and reached a peak during the debates surrounding the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The passage of the ACA in 2010 was a significant change in U.S. health care policy and, unlike the example above, came with intense partisan disagreement. The PCI indicates that was indeed a period of heightened polarization — one that continued to rise further for nearly a decade — illustrated by large numbers of news articles highlighting political disagreements.

Partisan Conflict and the Economy

As noted at the outset, political polarization is of relevance to economists because it may well matter for policies that have tangible effects on the economy. Increased partisanship can lead to high policy uncertainty, which in turn can delay consumer spending, business hiring and investment and hinder employment and economic growth. On a more positive note, a low level of the PCI indicates the availability of political compromise at any given time.

These effects appear to be sizeable. In my aforementioned 2018 paper "Partisan Conflict and Private Investment," I estimate that the rise in partisan conflict between 2007 and 2009 resulted in a 27 percent decline in corporate investment. Moreover, high levels of partisan conflict can also slow foreign investment, as evidenced in my 2019 paper "Does Partisan Conflict Deter FDI Inflows to the U.S.?."

Further, the relationship between the PCI and corporate credit spreads is documented in the 2018 article "Partisan Professionals: Evidence From Credit Rating Analysts," which found that economic analysts are more likely to adjust corporate credit ratings downward when partisan conflict is high. The authors also noted that partisan bias is more pronounced for analysts who are more politically active.

Conclusion

In this article, we documented through one measure — the PCI — how legislative disagreement has evolved and how that may affect the economy. Of particular interest were the effects on how businesses delay hiring and investment when facing high policy uncertainty. My research finds that these effects may well be significant.

Overall, the roots of partisan disagreement are of course complex, multifaceted and something we pass no judgement on. But as economists, no matter its origins, we must gauge the level of policy disagreements, place them in context and, critically, try to better understand the implications for the economy.

The PCI index is only one tool, so ideally more progress will be made in further understanding the multiple forces that shape national agreement or disagreement and then connect those to measures of economic performance.

Marina Azzimonti is a senior economist and research advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The indicator is constructed by computing the frequency of newspaper coverage of articles reporting political disagreement, normalized by the total number of news articles within a given period. The search is performed on major U.S. newspapers, including The Washington Post, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, The Wall Street Journal and Newsday.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Azzimonti, Marina. (June 2023) "Partisan Conflict in the U.S. and Potential Impacts on the Economy." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 23-20.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.