The Living Arrangements of Older Households

Key Takeaways

- The shares of older households living in their own homes and having two or more spare bedrooms have risen significantly, and older households have become less likely to move.

- The share of older households made up of a single generation has increased slightly, while the share of multigeneration households has decreased.

- The tendency of older individuals to age in place suggests that population aging will have substantial effects on housing markets.

In the past century, the share of the U.S. population aged 65 or older has more than tripled, rising from 4.7 percent in 1920 to 16.8 percent in 2020.1 This trend has been driven by both longer life expectancies and declining birth rates. In addition to having profound consequences for labor markets and government finances, an aging population will likely have substantial effects on housing markets. In this article, we document how the living arrangements of older households (those 65 or older) have changed over the past 50 years and discuss some of their potential implications.

Data on Older Households

Our main data sources are the decennial U.S. census and the Census Bureau's American Community Survey (ACS).2 These data show that older households have become more likely to live in single-generation, owner-occupied homes; more likely to have homes with spare bedrooms; and less likely to move. The increasing trend of seniors aging in place — coupled with their growing number — will significantly affect neighborhood composition and the availability of existing housing for new homeowners.

In addition to overall trends, we also consider differences between Black and White households and between singles and couples. Although most groups show similar trends, Black seniors remain less likely to own their homes and more likely to live in multigenerational housing.

Probability of Homeownership by Older Households

Homeownership rates among 65 and older are much higher now than they were 50 years ago. Table 1 shows that 67 percent of those aged 65 and older in 1970 lived in homes that they owned. By 2022, this share had risen to 79 percent. Almost all the growth in homeownership between 1970 and 2022 came from seniors living in single-generation households, such as singles or couples without children. The share of seniors living in multigenerational households (such as adults living with children and/or grandchildren) and owning the home increased only slightly.

After further segmenting by race, we see that the growth in homeownership rates for White households (14.3 percentage points) has been much larger than that for Black households (9.4 percentage points), expanding the gap between races. By 2022, over 80 percent of White seniors were homeowners, compared to 64 percent of Black seniors.

| All | Black | White | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing arrangement | 1970 | 2022 | 1970 | 2022 | 1970 | 2022 |

| All homeowners | 67.0% | 79.1% | 54.6% | 64.0% | 68.2% | 82.5% |

| All nonhomeowners | 27.5% | 17.9% | 41.9% | 31.7% | 26.1% | 14.4% |

| Single generation homeowners | 49.2% | 61.1% | 32.4% | 40.4% | 50.8% | 67.9% |

| Single generation nonhomeowners | 22.2% | 14.2% | 28.5% | 23.6% | 21.6% | 12.5% |

| Multigeneration homeowners | 17.8% | 18.0% | 22.2% | 23.6% | 17.4% | 14.6% |

| Multigeneration nonhomeowners | 5.3% | 3.7% | 13.4% | 8.1% | 4.5% | 1.9% |

| Institutions and other group quarters | 5.5% | 3.0% | 3.6% | 4.3% | 5.6% | 3.0% |

| Note: Numbers may not add to 100 percent due to rounding. Sources: 1970 census and 2022 American Community Survey. |

||||||

Single-Generation Homeownership Rates

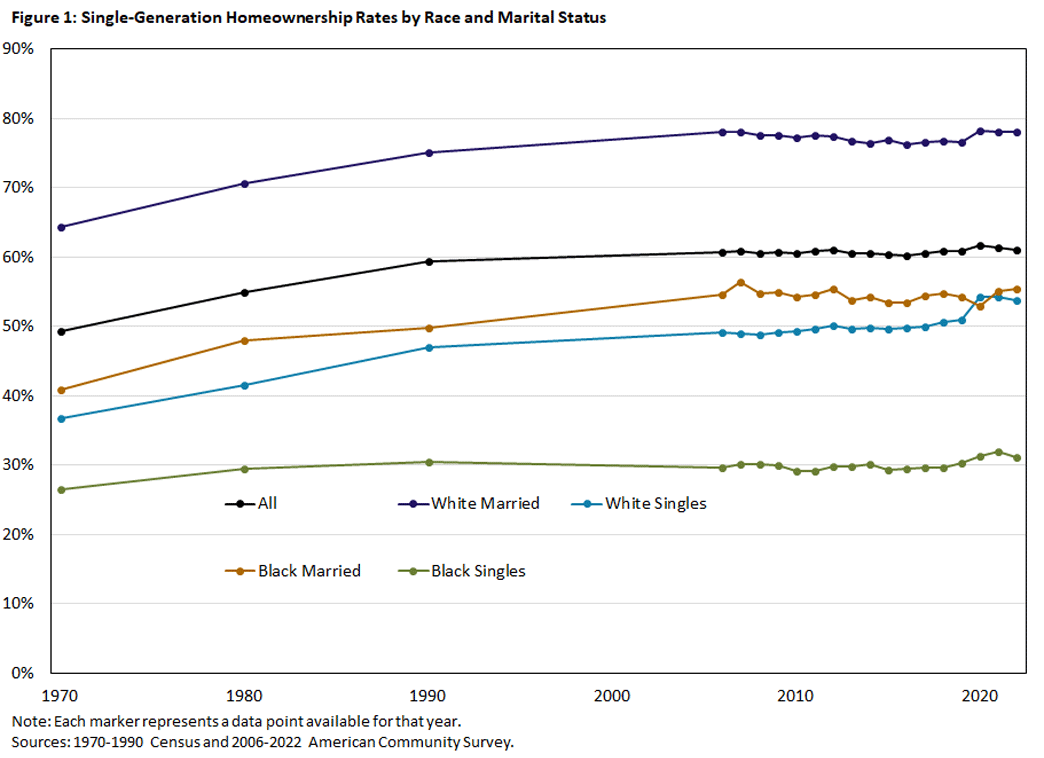

Figure 1 breaks down the share of older households that are single-generation homeowners (that is, the only generation living in the house) by race and marital status. Married couples have always been more likely to be single-generation homeowners than singles. Nonetheless, for all groups except Black singles, single-generation homeownership rates increased between 1970 and 2000, after which they have remained steady.

Even after controlling for marriage, White households are more likely to be single-generation homeowners. For example, the single-generation homeownership rate among White married couples currently stands at nearly 80 percent, about 23 percentage points higher than the rate for Black married couples.

Share of Older Households With Two or More Extra Bedrooms

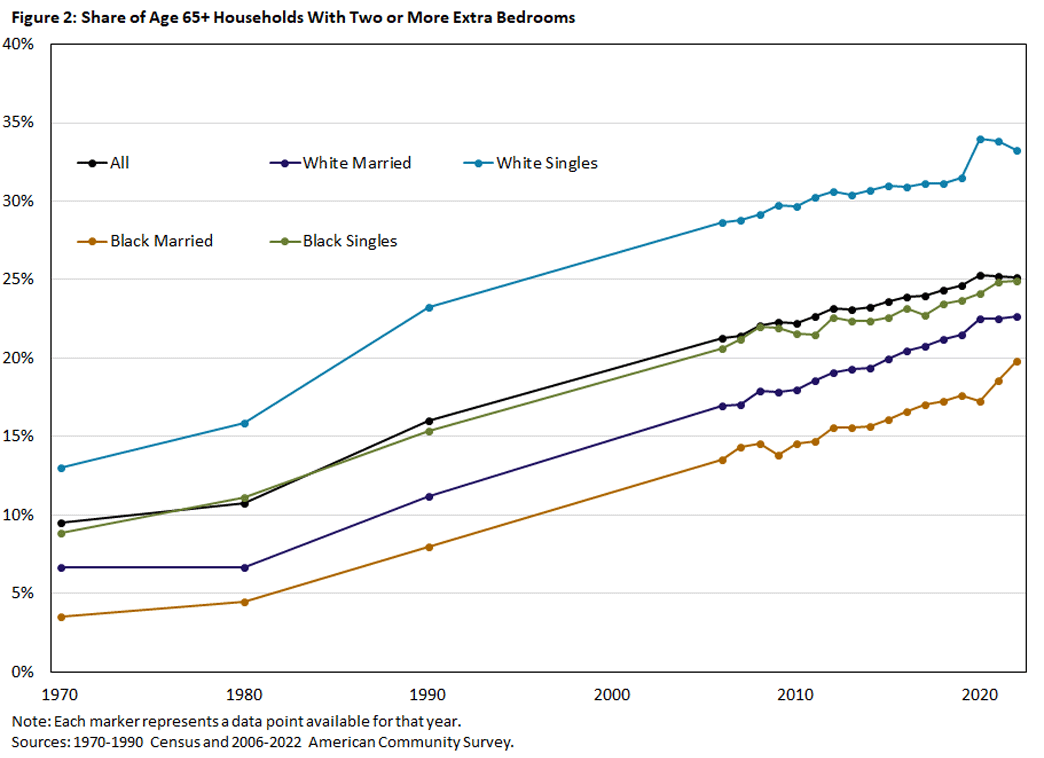

Older adults tend to have larger homes as measured by the number of extra bedrooms. A quarter of those aged 65 and older have at least two spare bedrooms in their home, compared to less than 12 percent of those aged 25-64. By this measure, house sizes have grown since 1970, when 10 percent of those aged 65 and older and 3 percent of those aged 25-64 had two or more spare bedrooms.

Figure 2 shows that the growth has been particularly rapid for White singles aged 65 and older, one-third of whom now have two or more spare bedrooms in their homes — an increase of 20 percentage points since 1970. That said, house sizes have risen for all groups since 1970, and the gap between Black and White seniors has remained roughly constant.

Older Households in Live-In Institutions or Other Group Quarters

Most seniors live independently, and the share has grown: In 2020, only 3.0 percent lived in institutional settings (such as nursing homes) or group quarters (such as shelters), down from 5.5 percent in 1970. This decline reflects the shift away from institutional health care and toward home health care.3 Black and White seniors have experienced divergent trends: As shown in Table 1, the share of older Black households who live in institutions or other group quarters has increased slightly (from 3.6 percent in 1970 to 4.3 percent in 2022), while the share for White seniors has fallen (from 5.6 percent to 3.0 percent).

As shown in Figure 3, single seniors are more likely to live in institutions or group quarters than married ones. The trends for the two groups also diverge, with the share of married seniors living in institutions or other group quarters staying fairly stable and the share for singles first rising and then falling.

Older Households Moving in the Past Year

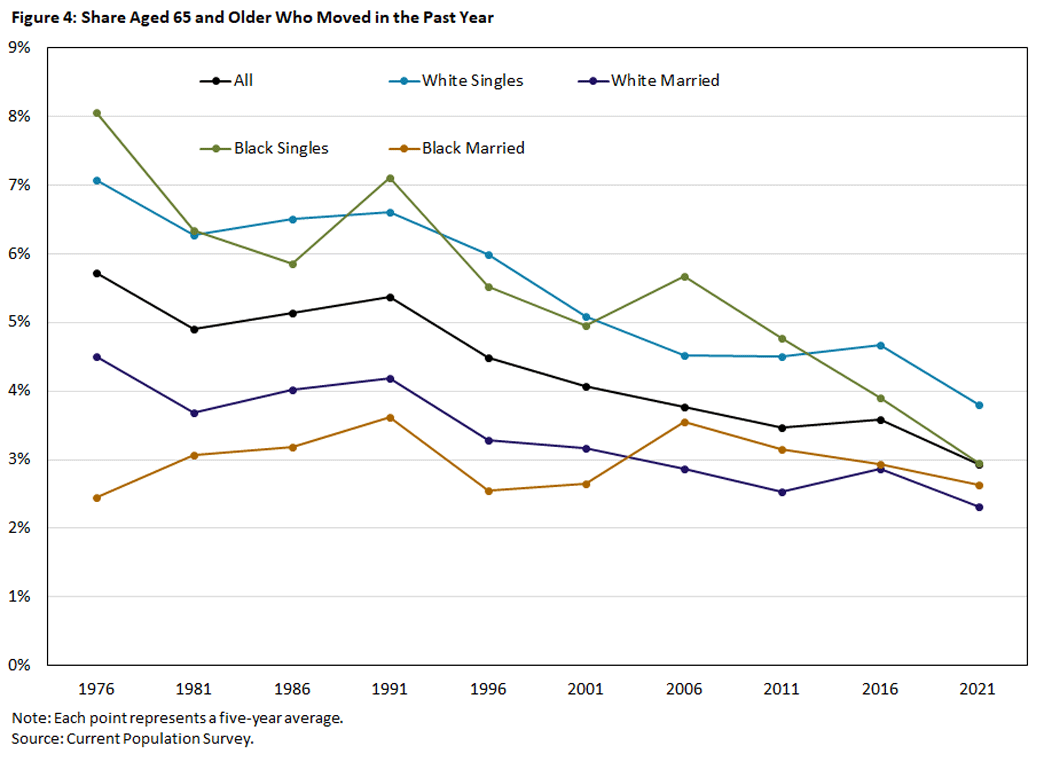

People of all ages are less likely to move now than they were 50 years ago. In 2023, 8 percent of those aged 25-64 had moved in the past year, compared to 16 percent in 1976. The rates for those aged 65 and older also fell sharply, from 6 percent in 1976 to 3 percent in 2023. The latter decline has coincided with the increase in homeownership and decrease in the share of households who live in institutions.

It is thus not surprising that most seniors choose to age in place. Over a quarter of adults between 65 and 74 report living in the same house for over 30 years, while nearly 40 percent of those aged 75 and up have lived in the same house for 30 or more years.4

Figure 4 shows disaggregated moving rates. Although singles are more likely to move than married couples, the decline in moving rates has been far more pronounced for singles. The moving rate for Black couples has in fact stayed roughly constant.

Shares of Older Households in Public Housing or Receiving Assistance

Although there has been a general trend toward homeownership among older households, many seniors still need assistance with housing costs. The share of older households receiving housing subsidies such as Section 8 vouchers has risen over time (from 0.5 percent in 1976 to 1.2 percent in 2023), as has the share living in public housing (from 2.2 to 3.1 percent).5 Over one-third of public housing residents are older adults.6 Black seniors — who generally receive less income and hold less wealth — are more likely to receive housing assistance. This is especially true for Black singles.

Implications

In the past 50 years, older households have become more likely to own their homes, live in single-generation households and live in homes with two or more spare bedrooms. The increased proportion of older households aging in place — amplified by an aging population in general — will have major implications for local public services such as schooling and home health care. Older households will need more care-related services, while demand for public school services should fall. Whether public school funding falls more or less than its demand is unclear. Households without school-aged children may be less willing to support public education, especially if there are other unmet needs. On the other hand, to the extent that public school quality affects home prices, older households may support continued funding.7 The desire to maintain home value should be particularly strong among older households hoping to leave bequests when they die.

The trend of aging in place will directly affect the geographic distribution of homes available to younger buyers. Because older individuals are generally more likely to own their homes, population aging will also reduce the supply of existing homes for sale. However, the overall effect of population aging on housing prices remains unclear.8 In the U.S., homeownership rates among younger cohorts are falling.9 There are many potential explanations for the decline, but an aging population could be one of them.

Regardless of its cause, the ongoing increase in house prices has left many older households with large amounts of their wealth tied up in illiquid assets. This raises interesting questions about intergenerational transfers. Older households who wish to support their children or grandchildren in paying for their education or purchasing their homes may hesitate if doing so requires selling their own homes. Financial products such as reverse mortgages potentially offer a solution, but reverse mortgages are used sparingly.10 Other potential transfer mechanisms include freeing funds through deferred home maintenance or a return to multigenerational households.

John Bailey Jones is a vice president and economist in the Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Yue Li is an associate professor of economics at the University at Albany, State University of New York, and Urvi Neelakantan is a senior policy economist in the Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

See the 2023 article "U.S. Older Population Grew From 2010 to 2020 at Fastest Rate Since 1880 to 1890" by Zoe Caplan.

For the figures, we dropped data from the 2000 census because the MARST variable appears to overstate the incidence of marriage among persons living in group quarters. In the 2000 5 percent sample, 20 percent of group quarters residents aged 18 and under are coded as married. In other census years, the share is less than 1 percent.

See, for example, Figure IV.1 of the "Medicaid Long Term Services and Supports Annual Expenditures Report (PDF)" for federal fiscal year 2020.

See the 2019 report "Senior Housing and Mobility: Recent Trends and Implications for the Housing Market" by Jung Hyun Choi, Laurie Goodman, Jun Zhu and John Walsh.

Authors' calculation from the Current Population Survey.

See the Department of Housing and Urban Development's Public Housing Dashboard.

See, for example, the 2009 paper "Why Do Households Without Children Support Local Public Schools? Linking House Price Capitalization to School Spending" by Christian Hilber and Christopher Mayer.

For example, in a cross-country analysis of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, the 2022 paper "Population Aging and House Prices: Who Are We Calling Old?" by Ye Jin Heo finds that older countries have lower home prices, due mainly to the prevalence of very old individuals.

See, for example, Figure 3 of the previously cited report "Senior Housing and Mobility: Recent Trends and Implications for the Housing Market."

See the 2017 paper "Reverse Mortgage Loans: A Quantitative Analysis" by Makoto Nakajima and Irina Telyukova.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Jones, John Bailey; Li, Yue; and Neelakantan, Urvi. (October 2024) "The Living Arrangements of Older Households." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 24-33.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.