Human Capital Investment: Would Higher-Order Skills Help Disconnected Youth?

Key Takeaways

- Human capital investments remain cost-effective well into young adulthood.

- A multidimensional approach to human capital development emphasizes developing self-reflection abilities and strategic thinking skills alongside traditional academic knowledge.

- Higher-order skills — like teamwork, critical thinking and self-control — offer high returns for disconnected youth and are well-compensated in the labor market.

In 2024, around 12 percent of people aged 16-24 in the U.S. were classified as "NEET" (not in employment, education or training, also considered "disconnected youth"). Drilling further down, a larger share of young women than young men are NEET, and those rates increase with age. Also, rural areas show higher rates of disconnected youth, with a peak of almost 30 percent among young Black men. High school graduation emerges as a critical inflection point: About half of NEET youth have high school diplomas but no college experience.

These disconnection rates seem to persist beyond early adulthood for some groups: According to Current Population Survey data, among Black men and women of any race, NEET rates for 25-29 year olds are higher than for 21-24 year olds.

This article outlines the critical role of human capital investment in addressing labor market challenges, particularly for disconnected youth. We provide empirical insights into why some young people remain detached from employment, education and training systems and discuss how strategic investments in human capital — both at the individual and societal level — can help limit youth disconnection.

The Challenges of Disconnected Youth

Several factors contribute to youth disconnection. A primary factor is caregiving responsibilities, whether it's for children, elderly relatives or self-care due to disability. About 54 percent of young NEET women and 32 percent of young NEET men provide child care or face their own disabilities or that of an adult they live with. Other factors play a role but are understudied:

- Poor labor market conditions

- Financial constraints that limit entrepreneurship, geographic mobility or educational access

- Information deficits

- A sense of nihilism among some young people who believe "nothing matters, nothing ever changes"

The Value of Human Capital Investment

A helpful framework for addressing the challenges of youth disconnection is human capital theory, or the idea that education and training are investments with costs sustained now and yields returned over time. Thinking of skills as investment makes explicit that human capital accumulation is a (very consequential) choice, not a circumstance.

Indeed, the evidence supporting the impact of skills development on labor earnings is among the strongest and most robust relationships in social science, with most studies showing that an additional year of education yields a 10-12 percent increase in future earnings. What is striking is that such figures are consistent across time, countries and various empirical designs, with an overall range of returns estimates between 6 and 18 percent across hundreds of research studies.1

The hypothesis that education builds skills is sometimes challenged by the so-called "signaling theory of education," which suggests that education doesn't build skills but rather functions as a credible signal that an individual is inherently skilled. However, there are reasons to doubt the signaling story in favor of the productive framework. A 2022 paper provides several reasons based on the positive effects from expanding compulsory education, a situation in which the signal is moot as everyone attains the same education level since it is mandatory.2 The paper's authors also study partial educational attainment without diplomas and find this also raises wages, despite no "piece of paper" to serve as a signal. Data from college graduates also demonstrate the economic value of specific coursework: While all studied students obtain the same diploma (meaning that they have the same signal), those who took courses with a higher skill content have higher earnings.

The Timing of Human Capital Investment

Research by James Heckman and colleagues highlights that the timing of skill building is of the essence. Heckman's vast body of work highlights two key concepts:

- Self-productivity, or skills that build upon previously developed skills

- Dynamic complementarity, or early investments that make later investments more effective

When applied to human capital accumulation, these two concepts give rise to the so-called "Heckman Curve." The Heckman Curve depicts the negative-sloped returns to human capital investments as individuals age and, for a given cost level, identifies the age at which the returns from human capital interventions become smaller than their costs. All in all, Heckman maintains that interventions targeted at younger children yield higher returns than programs aimed at older individuals.

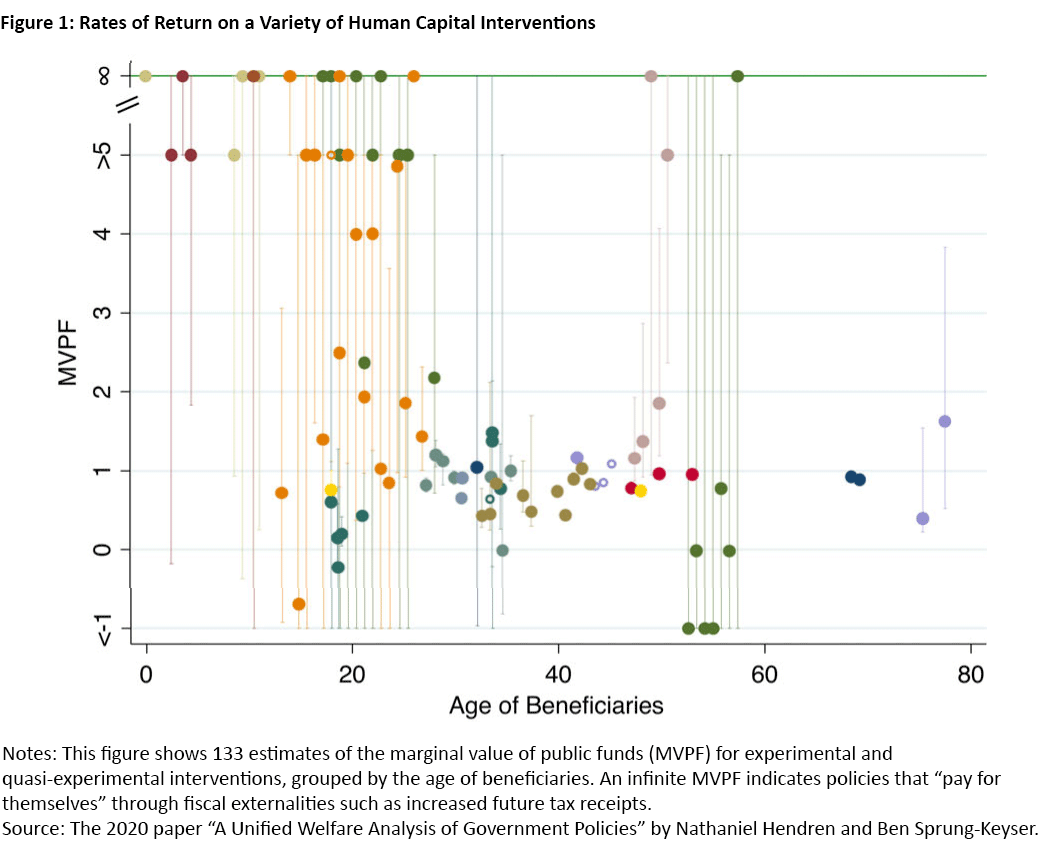

While the focus on early childhood education is well-accepted and warranted, there are important nuances to offer. On the one hand, lower returns are not equivalent to low returns. Later interventions can still offer benefits, even if smaller than earlier interventions. And even when early childhood programs are available, disparities in opportunity may result in imperfect access to them, so that later human capital building may still be worthwhile. On the other hand, newer research has shown that human capital interventions up to age 25 can still demonstrate high returns and even "pay for themselves" in future tax revenue.3

Figure 1 illustrates the point that various interventions (including college tuition subsidies) can be as valuable as early childhood programs. Some research has suggested that this is because many programs to build human capital before age 20 take place in school, an especially efficient mode of delivery.4 This finding has significant implications for policymakers, suggesting that a broader range of educational investments remains worthwhile throughout childhood and young adulthood.

Building Foundational and Higher-Order Skills

Building skills is key to enhancing earnings potential for young workers, with human capital accumulation from early childhood to young adulthood delivering especially high returns. Economic research offers some insights on how to implement policy interventions that enhance skill accumulation. For foundational skills like numeracy and literacy, the evidence strongly supports providing additional resources to schools. A 2016 paper finds that flexible funding that allows schools to reduce class sizes, improve facilities and increase instructional time reliably produces positive outcomes.5 By contrast, performance-based incentives and test-based accountability show mixed results unless paired with adequate resources.

Beyond these basics, recent literature emphasizes the growing importance of "higher-order" or "noncognitive" skills like patience, self-control, teamwork, grit and critical thinking. A 2017 paper finds that the economic returns to social skills have more than doubled for young workers entering the labor market in the 2000s compared to the 1980s.6 And a 2021 working paper further confirms the positive trend, showing "an increasing relevance of social skills in top managerial occupations."7

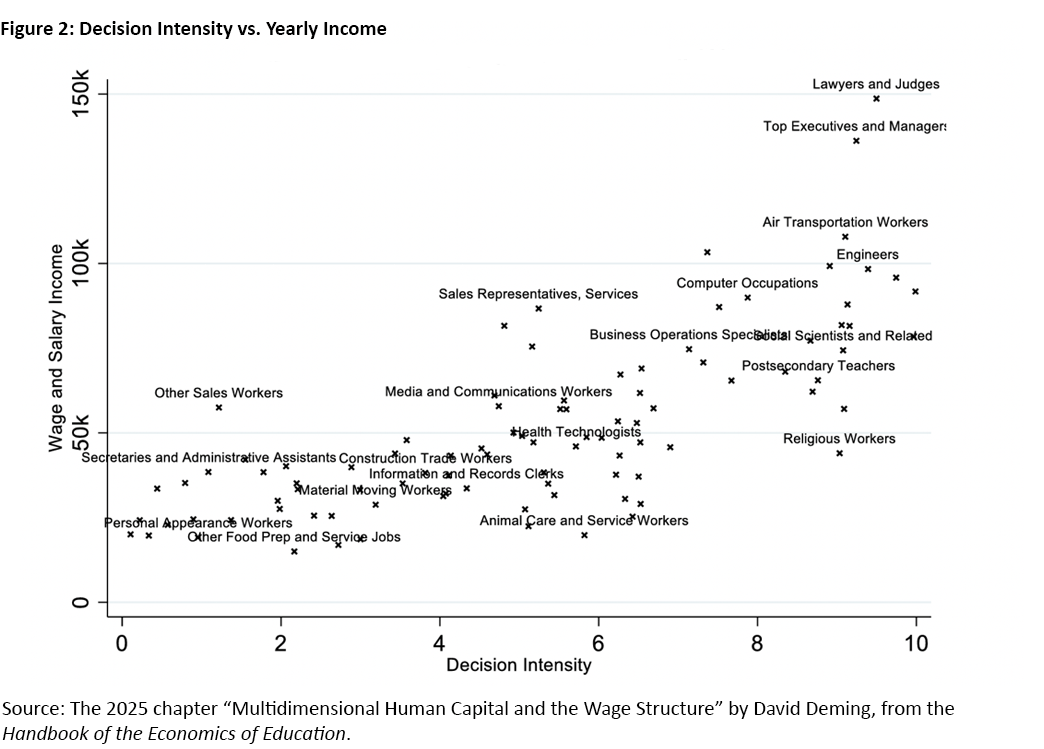

Figure 2 illustrates that jobs involving decision-making indeed command higher wages and effective decision-making requires higher-order skills. Encouragingly, research suggests these capabilities are malleable and can be developed through targeted interventions, rather than being fixed traits determined by genetics or early environment.8 For instance, a 2018 paper finds that financial literacy programs for German high school students reduced time inconsistency and lowered discount rates, encouraging patience and long-term decision making.9

Human Capital as Multidimensional

While the demand for college-educated workers increased throughout the 2000s, the return to cognitive skills alone has declined during the same period.10 The explanation lies in understanding human capital as multidimensional and emphasizing the importance of noncognitive skills. College education provides more than academic knowledge: It develops the higher-order skills increasingly valued in today's economy.

A multidimensional human capital framework reconceptualizes workers not as mere production inputs, but as decision-making agents who optimize their contributions through task selection and collaboration. Yet often our view of productivity is simply augmenting (learn more, do more, produce faster). Modern jobs, however, require this approach less and less, valuing workers who can instead self-reflect, identify their strengths and deal with their weaknesses by either collaborating with others on complex tasks or delegating them altogether.

Implications for Policy and Practice

To conclude, economic research on human capital offers three insights for disaffected youth and their educators:

- Human capital investments have significant consequences for both individuals and society.

- Higher-order skills like teamwork and grit offer the highest returns, extending beyond traditional academic metrics.

- We must reconceptualize workers as decision-making agents, equipping them accordingly.

This framework offers a promising path forward for addressing the persistent challenge of disconnected youth. Investing strategically in human capital development — particularly the higher-order skills that enable adaptation to economic volatility — can help more young people successfully engage with education and employment opportunities. The evidence is clear that investments in human capital development yield substantial returns for individuals and society alike, making them crucial for addressing labor market disconnection and fostering economic resilience.

Claudia Macaluso is a senior research economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

See, for example, the 2022 paper "Four Facts About Human Capital" and the 2025 chapter "Multidimensional Human Capital and the Wage Structure" from the Handbook of the Economics of Education, both by David Deming.

See the 2022 paper "Signaling and Employer Learning With Instruments" by Gaurab Aryal, Manudeep Bhuller and Fabian Lange.

See the 2020 paper "A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies" by Nathaniel Hendren and Ben Sprung-Keyser.

See the previously cited 2025 chapter "Multidimensional Human Capital and the Wage Structure" from the Handbook of the Economics of Education by David Deming.

See the 2016 paper "The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence From School Finance Reforms" by C. Kirabo Jackson, Rucker Johnson and Claudia Persico.

See the 2017 paper "The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market" by David Deming.

See the 2021 working paper "The Demand for Executive Skills" by Stephen Hansen, Tejas Ramdas, Raffaella Sadun and Joe Fuller.

See the chapter "Skills and Human Capital in the Labor Market (PDF)" by David Deming and Mikko Silliman in the forthcoming Handbook of Labor Economics.

See the 2018 paper "The Impact of Financial Education on Adolescents' Intertemporal Choices" by Melanie Lührmann, Marta Serra-Garcia and Joachim Winter.

See, for example, the 2014 paper "The Changing Roles of Education and Ability in Wage Determination" by Gonzalo Castex and Evgenia Kogan Dechter, the 2020 paper "Extending the Race Between Education and Technology" by David Autor, Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz, and the 2022 paper "The Rising Return to Noncognitive Skill" by Per-Anders Edin, Peter Fredriksson, Martin Nybom and Björn Öckert.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Macaluso, Claudia. (June 2025) "Human Capital Investment: Would Higher-Order Skills Help Disconnected Youth?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-24.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.