Rounding Up: The Impact of Phasing Out the Penny

Key Takeaways

- The U.S. government is expected to stop producing new pennies for circulation by early 2026. In 2024, the Treasury incurred a seigniorage loss of $85.3 million on penny production.

- As pennies phase out, businesses are likely to round cash transactions to the nearest 5 cents, resulting in a "rounding tax."

- Using data from the 2023 Diary of Consumer Payment Choice, we estimate that rounding tax could cost U.S. consumers approximately $6 million annually.

- Eliminating the nickel in addition to the penny could result in significantly higher rounding costs: up to $56 million per year for consumers.

After more than two centuries in circulation, the penny is getting retired. In May, the U.S. Treasury Department placed its final order for penny blanks, which are the flat metal discs the U.S. Mint transforms into coins. These remaining blanks are expected to run out by early 2026, at which point production of new pennies will officially cease.1

The key motivation is production costs. According to the U.S. Mint's 2024 Annual Report (PDF), producing and distributing a single penny costs 3.69 cents, nearly four times its face value. As a result, the Treasury incurred a seigniorage loss of $85.3 million last year from minting more than 3 billion new pennies. These mounting losses have sparked a re-evaluation of the penny's role in an increasingly digital economy.

However, even if the cost of producing a penny exceeds its face value, one could argue that the social benefits it provides to the U.S. economy may outweigh its production costs and that eliminating the penny could result in a loss of welfare. An important social benefit is the pricing flexibility it enables. Without the penny, businesses would need to round cash transactions to the nearest 5 cents, potentially increasing the cost of a given consumption basket for U.S. consumers. In this article, we quantify this rounding cost using the latest data from the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice (DCPC).

The Impact of Rounding on Consumers

With the removal of the penny, cash transactions will likely be rounded to the nearest nickel. A common rounding rule is as follows: If the final digit of a purchase ends in 3, 4, 8 or 9 cents, the total will be rounded up; if it ends in 1, 2, 6 or 7 cents, it will be rounded down. Transactions ending in 0 or 5 cents are not rounded.

At first glance, the net effect of rounding might appear neutral: Assuming that the final digits of transaction totals are uniformly distributed, the gains from rounding down and losses from rounding up should cancel out. However, if transaction amounts are skewed toward values that round up, consumers end up consistently paying more, creating what's referred to as a rounding tax.

Past studies have investigated the impact of penny rounding, for both the U.S. and Canada.2 These studies rely on simulated transaction values based on price information from individual retailers and assumptions on purchasing bundles and sales taxes, leading to mixed conclusions about whether rounding benefits or harms consumers.

In contrast, our analysis uses data from the 2023 DCPC, a Federal Reserve-sponsored survey that tracks real payments from a nationally representative sample of consumers. Participants were randomly assigned a three-day period between Sept. 29 and Nov. 2, 2023, during which they recorded every transaction. This rich, representative dataset avoids many of the limitations and assumptions in earlier work.

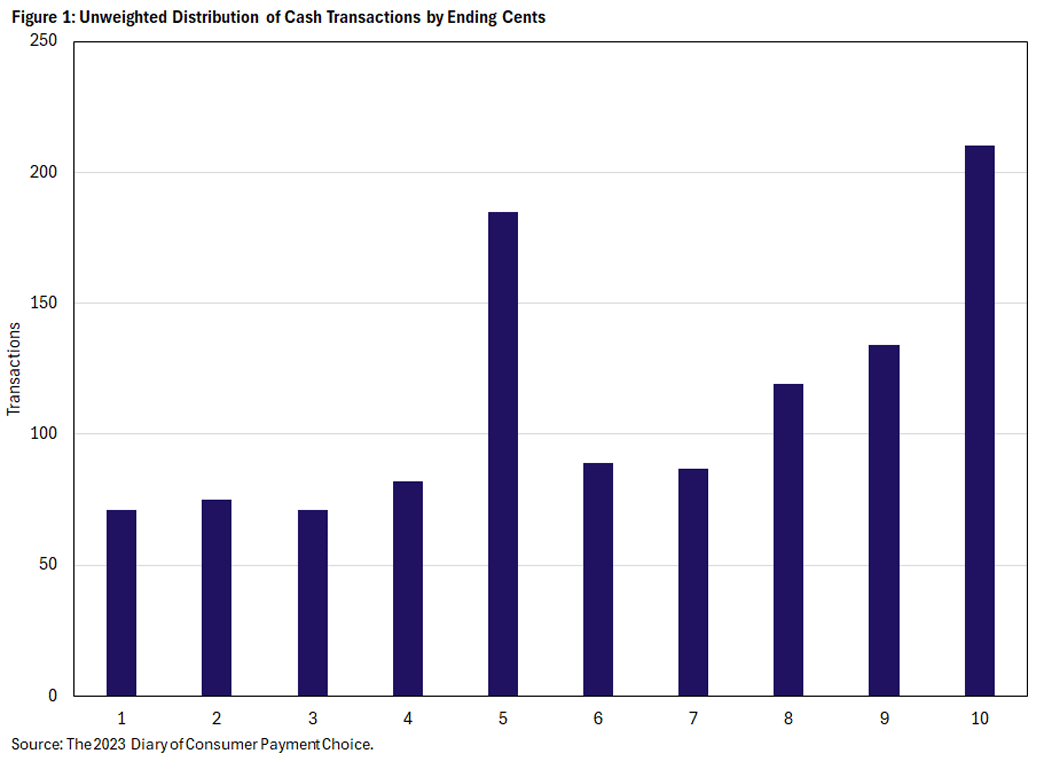

The DCPC includes 24,728 transactions reported by 4,671 adults. Of these, 3,559 transactions were paid in cash. Among the cash transactions, 2,436 ended in whole dollars and would not be affected by rounding. Figure 1 below shows the distribution of the remaining 1,123 cash transactions by their ending cents. About 35 percent of transactions ended in 0 or 5 cents, so they also wouldn't be affected by rounding. Among the transactions affected by rounding, the distribution is skewed: Transactions are more likely to end in 3, 4, 8 or 9 cents than the other digits, suggesting that rounding may indeed result in a net cost to consumers.

Based on this sample, we estimate the overall impact of rounding. First, we calculate the rounding gain or loss for each individual DCPC participant. We then aggregate these effects using each participant's sampling weight to generate a nationally representative estimate. Scaling up from three days and 4,671 individuals to the full adult U.S. population (258.3 million) over a full year, we estimate that rounding to the nearest nickel would cost consumers about $6.06 million annually, assuming transaction patterns remain unchanged.

What About the Nickel?

With the penny being retired, attention may soon turn to the nickel. Ironically, eliminating the penny could increase demand for nickels, which are even more costly to produce. In 2024, it cost 13.8 cents to mint a nickel — more than double its face value — resulting in a seigniorage loss of $1.75 for every $1 issued in nickels. The Treasury incurred a seigniorage loss of $17.7 million last year from minting 202 million new nickels, notably lower than the loss incurred by minting pennies. However, seigniorage losses in the two previous years — $78.0 million in 2022 and $92.6 million in 2023 — were much higher due to larger production.

Removing the nickel would significantly raise the rounding burden on consumers. Using the same DCPC dataset, we estimate the impact of eliminating both pennies and nickels. In this scenario, merchants would round up transactions ending in 5 or more cents to the nearest dime and round down the rest.

Figure 1 suggests that many transactions cluster at 5, 8 and 9 cents. As a result, eliminating nickels in addition to pennies would amplify the rounding tax. Our calculations show that this dual phase-out could cost consumers approximately $55.58 million per year — more than nine times the cost of phasing out the penny alone.

Further Remarks

The phase-out of the penny marks both a symbolic and practical transition. It reflects rising production costs, reduced use of physical cash and the growing dominance of electronic payments. Understanding the effects of this change — especially the rounding impact on consumers — is a timely and relevant policy issue.

With this move, the U.S. joins a growing list of countries that have phased out low-denomination coins:3

- Australia discontinued its 1-cent and 2-cent coins in 1992

- New Zealand eliminated its 1-cent and 2-cent coins in 1990 and its 5-cent coin in 2006.

- Canada ceased penny production in 2012.

These examples illustrate how economies adapt to the absence of small coins.

Our analysis offers a first-pass estimate of the rounding effect using a representative survey of U.S. consumers. We find that the annual rounding tax from eliminating the penny is relatively modest compared to the Treasury's losses from producing it. However, removing the nickel would impose a significantly larger burden on cash users.

It is important to note that U.S. pennies will remain legal tender even after production ceases. Consumers can continue using them in transactions, though their availability will gradually decline as existing coins fall out of circulation. In response, businesses will begin rounding cash transactions to the nearest 5 cents, which is common in countries that have phased out low-denomination coins. Consequently, the rounding tax we estimated will be realized gradually. Meanwhile, electronic payments (such as credit and debit card transactions) will remain unaffected and continue to be processed at exact amounts. As electronic payments become more widespread, both the share of cash transactions and the need for rounding are likely to continue to decline. Together, these developments will help mitigate the overall impact of the rounding tax.

There remain important avenues for future study. We have assumed fixed transaction patterns in the estimation, but changes in merchant pricing strategy and consumer payment behavior in response to coin phase-out may also affect the impact of rounding. Moreover, broader considerations — such as the efficiency and convenience of alternative means of payment, their associated externalities and the environmental costs of coin production — should be included in a more comprehensive cost-benefit analysis.

Zhu Wang is vice president for research in financial and payments systems and Russell Wong is a senior economist, both in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. The authors thank Vinh Phan for excellent research assistance.

See the May 22 article "Treasury Sounds Death Knell for Penny Production" by Oyin Adedoyin.

Examples of papers discussing ending the penny in the U.S. include the 2001 paper "Eliminating the Penny from the U.S. Coinage System: An Economic Analysis" by Raymond Lombra and the 2007 paper "Time to Eliminate the Penny from the U.S. Coinage System: New Evidence" by Robert Whaples. Examples of papers discussing ending the penny in Canada include the 2003 paper "Have a Penny? Need a Penny? Eliminating the One-cent Coin from Circulation" by Dinu Chande and Timothy C.G. Fisher and the 2018 paper "Eliminating the Penny in Canada: An Economic Analysis of Penny-Rounding on Grocery Items" by Christina Cheung.

Technically, the U.S. has some prior experience phasing out low-denomination coins, having done away with the half-cent in 1857, as noted in the 2020 article "Will the Penny Get Pitched?" by Tim Sablik.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Wang, Zhu; and Wong, Russell. (July 2025) "Rounding Up: The Impact of Phasing Out the Penny." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-27.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.