Five Decades of Decline: U.S. Construction Sector Productivity

Key Takeaways

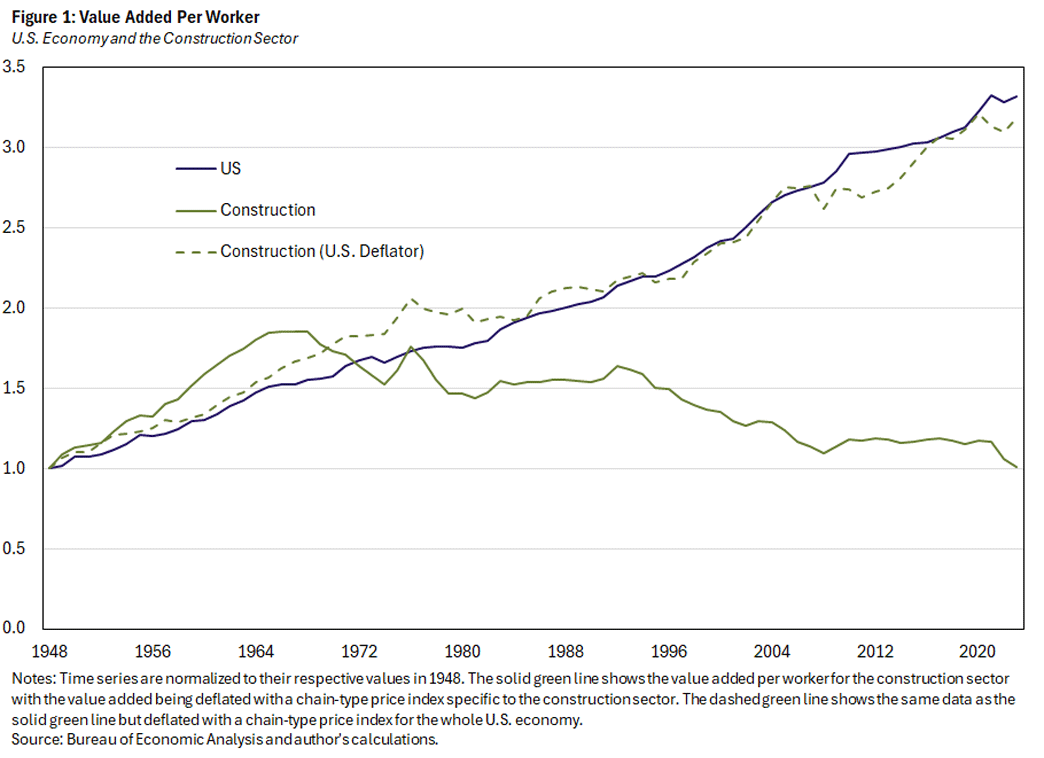

- Construction labor productivity fell by more than 30 percent from 1970 to 2020, while overall U.S. economic productivity doubled over the same period.

- Despite potential biases in price deflators, multiple studies confirm that the productivity decline is real, with physical measures like housing units per worker showing similar stagnation.

- Increasing land-use regulations may be a plausible cause for the decline, as more strict land-use regulations disincentivize construction companies from pursuing larger projects, keeping them relatively small. In addition, this reduces incentives for technological innovation and economies of scale.

Historically, the U.S. economy has displayed robust, positive productivity growth. According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, labor productivity (that is, real output per worker) has more than tripled over the period 1948-2023. Moreover, this positive trend is visible in almost every broad sector of the U.S. economy.

However, there is one notable exception: construction. Labor productivity in U.S. construction in 2023 was essentially the same as it was in 1948. More importantly, as displayed in Figure 1, labor productivity in U.S. construction has actually been falling since the 1970s.

This phenomenon of falling productivity in U.S. construction was emphasized by the 2023 working paper "The Strange and Awful Path of Productivity in the U.S. Construction Sector."1 Real output per worker in 2020 was more than 30 percent lower than in 1970, following one of the most persistent productivity declines in any major industry.

This presents a puzzling contradiction: While other goods-producing sectors (such as mining and manufacturing) have achieved remarkable productivity gains over the past few decades, the construction sector — which is responsible for building the homes, offices and infrastructure needed for our growing economy — has experienced a prolonged and quite severe productivity decline.

This decline has significant implications not only for housing affordability but for overall economic growth. Construction represented about 4.5 percent of U.S. GDP in 2024. While this sector is less than half of manufacturing in terms of value added, the importance of a decline in construction productivity for its aggregate counterpart cannot be overstated.

The construction sector is an important supplier of capital to other sectors, so a decline in construction productivity can be amplified to the aggregate. In fact, a 2022 paper concludes that the construction sector alone accounted for about one-third of the decline in trend GDP growth since WWII.2 This loss is equivalent to about $1 trillion every five years.3 Similarly, a 2023 working paper estimates that, if construction productivity had grown at even a modest 1 percent annually since 1970, annual aggregate labor productivity growth would have been roughly 0.18 percentage points higher.4 This difference would have resulted in current aggregate productivity — and likely income per capita — being about 10 percent higher than actual levels.

The magnitude of this decline becomes particularly striking when compared to overall economic performance. During the 1950s and 1960s, construction productivity actually grew at rates that matched or exceeded the broader economy. However, around 1970, construction productivity began a sustained downward trajectory that has continued for five decades. While aggregate U.S. labor productivity tripled between 1950 and 2020, its measure for construction remained essentially the same. This divergence is especially notable when compared with manufacturing, which experienced a large increase in labor productivity over the same period despite dealing with similar physical assembly and configuration challenges.

Is the Productivity Decline Driven by Measurement Error?

Given the overall growth of the U.S. economy and the construction sector's apparent importance to the economy, a secular decline in U.S. construction productivity seems peculiar at first. As a result, some observers in the literature were initially skeptical about this phenomenon and believed that the drop in construction productivity was primarily driven by measurement issues.

Labor productivity requires only two components:

- Real output (that is, value added in constant dollars)

- A measure for labor

The latter is typically measured by the number of either full-time equivalent payroll workers or hours worked by these employees.

It is important to point out that construction establishments use a lot of subcontractors and/or undocumented immigrants, which are not included in traditional measures of labor. However, correcting these measurement "errors" does not reverse the declining trend in construction productivity. On the contrary, correcting productivity figures for subcontractors or undocumented immigrants would only display a larger decline in its productivity, since such a correction would mean more workers producing the same level of output. As a result, a decline in labor productivity cannot be solely caused by mismeasurement in labor variables.

Productivity Measurement and Deflators

One of the main points of controversy in the construction productivity debate lies in its deflators.5 When labor productivity is deflated using the GDP deflator for the whole economy, construction productivity essentially follows the economy's upward trend, as seen in Figure 1. It is important to note that this observation does not immediately imply that commonly used deflators for the construction sector are wrong. However, increasing output prices do play a big role in understanding productivity for the construction sector.

Given that construction productivity calculations depend heavily on price deflators used to convert nominal construction spending into real output measures, the question of measurement error in these deflators has been central in the construction productivity debate. A 2025 working paper specifically investigated whether measurement problems in these deflators could account for the observed productivity decline.6 It focuses on potential biases arising from unobserved improvements in structure quality — such as better insulation, more energy-efficient systems and higher-quality materials — that are not fully captured in official price measurements.

Using three different analytical approaches — econometric techniques, detailed construction cost data and observable quality measures from property tax assessors and homeowner surveys — this paper finds evidence of upward bias in construction price deflators. However, the magnitude of this bias was not large enough to fundamentally alter existing conclusions about poor construction productivity performance. Its most generous estimates suggest that unobserved quality improvements may have biased construction sector productivity growth downward by at most 0.5 percentage points per year from quality-related factors, with additional small biases from other measurement issues.

Even accounting for these measurement problems, this paper concludes that "productivity growth may well have been quite low in construction, even if it has not been as low as implied by official statistics." Construction productivity growth would still be essentially flat rather than negative, but it would remain far below other major industries: After adjusting for all potential measurement biases, construction productivity growth would still lag behind the next-lowest performing industries by about 1 percentage point annually and behind overall economic productivity growth by nearly 2 percentage points. These findings reinforce that the construction sector's productivity challenges represent a real economic phenomenon with substantial implications for long-term U.S. economic growth.

This view is also supported by earlier studies and has been recently corroborated as well.7 When these studies examined physical measures of productivity (such as housing units built per worker), they found similar patterns of stagnation or decline that do not rely on potentially problematic price adjustments. Additionally, the sector has shown deteriorating efficiency in converting materials into finished products, and there appears to be limited reallocation of resources from less productive to more productive areas, which is a mechanism that typically helps drive productivity growth in well-functioning markets.

Construction Productivity Decline and Land-Use Regulation

Since the decline in construction productivity does not seem to be a mere measurement problem, a natural follow-up question is: What caused this decades-long decline in the productivity of the construction sector? An interesting hypothesis has recently been put forward by a 2024 working paper: the rise of land-use regulation.8

Using historical data from the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the authors construct a series on construction productivity (that is, housing units started per worker) from 1900-2023. Its analysis reveals an inverted U-shaped curve — what the authors term a "Kuznets curve" — for construction where labor productivity displayed no noticeable trend between 1900 and 1940, boomed after WWII and then sharply decreased again after 1970. This historical pattern demonstrates that technological progress in construction is not inherently impossible, making the post-1970 decline all the more striking. Then, the authors show that the timing of this productivity reversal roughly coincides with America's embrace of increasingly restrictive land-use controls and building regulations.

The paper's argument is relatively straightforward: Project-level building regulations systematically reduce the size of individual construction projects by making larger developments more difficult to approve through lengthy permitting processes and community opposition. Through a structural model, the paper demonstrates that, when developers face lower approval probabilities for larger projects, it is optimal for these construction firms to pursue smaller developments. In turn, this leads to smaller construction companies since these firms cannot efficiently manage numerous small projects scattered across different locations.

This regulatory constraint creates a vicious cycle that undermines productivity growth. Smaller construction firms have reduced incentives to invest in technological innovation and process improvements because the benefits of such investments cannot be spread across as many projects or housing units. Empirical evidence from the paper supports this theory: Areas with stricter land-use regulation have significantly smaller and less productive construction establishments. Furthermore, patenting activity in construction stagnated after 1970, while manufacturing patents continued to grow. In the end, the paper estimates that construction productivity could be 60 percent higher if firm sizes matched those in manufacturing. This regulatory explanation helps explain why construction has diverged so sharply from other sectors that have continued to benefit from technological progress and economies of scale.

Conclusion

The decline in construction productivity represents one of the most significant and persistent sectoral challenges facing the U.S. economy. While measurement issues may account for some of the observed decline, most evidence seems to point out that genuine productivity problems have plagued the industry for more than five decades.

The stakes of addressing this challenge extend far beyond construction companies themselves. With construction productivity problems contributing to reduced housing affordability and slower overall economic growth, finding solutions has become critical. The regulatory hypothesis offers a potentially actionable path forward, suggesting that reforms to land-use and building approval processes could help restore the technological dynamism that the sector demonstrated during its post-World War II boom.

As policymakers grapple with housing shortages and infrastructure needs, understanding and addressing the root causes of construction's productivity stagnation will be essential for promoting U.S. productivity growth.

Chen Yeh is a senior economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Authored by Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson.

See the 2022 paper "Aggregate Implications of Changing Sectoral Trends" by Andrew Foerster, Andreas Hornstein, Pierre-Daniel Sarte and Mark Watson.

See the 2024 working paper "Why Has Construction Productivity Stagnated? The Role of Land-Use Regulation" by Leonardo D'Amico, Edward Glaeser, Joseph Gyourko, William Kerr and Giacomo Ponzetto.

See the previously mentioned working paper "The Strange and Awful Path of Productivity in the U.S. Construction Sector."

This point is highlighted in "The Strange and Awful Path of Productivity in the U.S. Construction Sector."

See the 2023 working paper "Reexamining Lackluster Productivity Growth in Construction" by Daniel Garcia and Raven Molloy.

For the earlier studies, see the 1981 paper "An Examination of the Productivity Decline in the Construction Industry" by Kemble Stokes and the 1985 paper "Why Construction Industry Productivity Is Declining" by Steven Allen. The paper "The Strange and Awful Path of Productivity in the U.S. Construction Sector" corroborated these studies.

See the previously cited paper "Why Has Construction Productivity Stagnated? The Role of Land-Use Regulation."

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.