Why Richmond Got a Reserve Bank

On Nov. 16, 1914, the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond opened its doors, with fewer than 50 employees, in a former store building at 1109 East Main St. It was one of 12 regional Reserve Banks that were opening across the nation and that, along with the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., made up the new Federal Reserve System. But why did Richmond get a Fed?

The Federal Reserve Act that was signed into law in December 1913 called for the establishment of a Reserve Bank Organization Committee that “shall designate not less than eight nor more than twelve cities to be known as Federal reserve cities” and establish districts that would each contain just one Federal Reserve city. Within each city, the Committee was responsible for supervising the organization of a Federal Reserve Bank. Appointed to the Reserve Bank Organization Committee were: Treasury Secretary William McAdoo, Agriculture Secretary David Houston, and Comptroller of the Currency John Williams. The initial preparation of a districting plan fell to a group of experts led by Henry Parker Willis, an economist who helped Congress craft the Federal Reserve Act and who would later serve as secretary for the first Federal Reserve Board.

The Federal Reserve Districts were not required to follow state boundaries, but given the membership and capitalization of Reserve Banks laid out in the Act, it made sense for the districts to be apportioned with concern for the distribution of banking assets at the time. Thus, since banking resources were concentrated in the Northeast, that area had to be divided into smaller districts than, say, the West Coast where economic activity was more spread out.

In no way was it clear at the outset that Richmond would get a Reserve Bank. Many believed that a Reserve Bank between Philadelphia and Atlanta was unnecessary, and if one should prove necessary, Washington, D.C., or Baltimore would be better suited for a bank headquarters. But, Richmond decided to fight to have a Reserve Bank and within a week of the signing of the Federal Reserve Act, members of the Richmond community from both the public and private sectors formed the “Committee on Locating a Federal Reserve in Richmond.” The committee concentrated its promotional efforts in North Carolina and South Carolina so that by the time Charlotte, N.C., and Columbia, S.C., decided to mount campaigns to host their own Reserve Bank—two of 37 cities to ultimately do so—many leading bankers in those states had already endorsed Richmond.

In its final brief to the Committee, the Richmond group emphasized its key advantages: (1) The city provided a link between the South Atlantic and the Northeast; (2) The city had extensive transportation and communication facilities, including north-south and east-west rail lines and river/coastal waterways—which allowed efficient contact with every point in the proposed district and a natural point for clearing checks and distributing currency; (3) The city had extensive banking connections—its national banks were lending in the 13 Southern states more than the national banks of any city except New York; and (4) The city was important as a commercial and financial center.

Once the Reserve Bank cities were chosen on April 2, 1914, there was, not surprisingly, outcry from cities that were not chosen. The outcry included accusations that the choice of Richmond as a Reserve Bank city was entirely politically motivated: Rep. Carter Glass, who played a major role in crafting the Reserve Act and worked within Congress to secure its passage, was a Virginian, as were President Wilson and John Williams. In response to those accusations and to further justify their choices of Reserve Bank cities, the Committee released a poll of over 7,000 national banks that, according to the Committee and to where the Reserve Banks ultimately landed, were influential in the final location of Reserve cities. In that poll, Richmond had more first and second choice votes from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia banks than any other city.

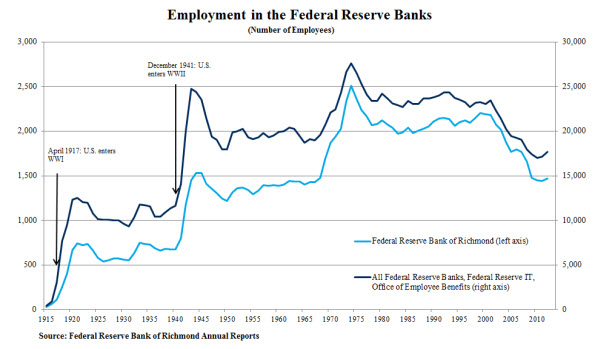

Since its inception in 1914, the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond has changed considerably. There are now almost 1,500 employees at the Richmond Bank spread between the Richmond headquarters and its branches in Baltimore (opened in 1918) and Charlotte (opened in 1927). Developments such as changes in check usage and the expanded use of technology have influenced the way that all of the Federal Reserve Banks operate. Still, the Reserve Bank districts remain where they were set by the Committee in 1914, with the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond continuing to serve the Fifth Federal Reserve District, as was envisioned by its proponents over 100 years ago.

For more information, please refer to:

Gerena, Charles, A Division of Power, Region Focus Winter 2007

Waddell, Sonya, The Richmond Fed at 100 Years, Econ Focus First Quarter 2014

Parthemos, James, A Reserve Bank for Richmond, Economic Review January/February 1991

Have a question or comment about this article? We'd love to hear from you!

Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.