Raise the Wage?

Some argue that there's no downside to a higher minimum wage, but others say the poor would be hit hardest

Calls to raise the minimum wage can be found anywhere from political speeches to the lyrics of popular rap artist Kanye West. In the past few years, many efforts to raise the minimum wage have been made on the national, state, and even local level, including a drastic local minimum wage hike to $15 in Seattle, a bill to increase the minimum wage to $10.10 in Maryland, and an indexed $10.10 minimum wage proposal endorsed by the White House. Critics of the policy claim that economic theory clearly supports their position, while supporters claim that the empirical evidence is all over the map and point to numerous examples of research that seem to fly in the face of past theoretical conclusions about the minimum wage. If there are seemingly compelling theoretical and empirical justifications both for and against the minimum wage, who should policymakers listen to? Does a minimum wage make low-income workers, the group its proponents desire to help, better off, worse off, or some of each?

The Decline of the Historical Consensus

Until around 20 years ago, there was a substantial divide between public opinion and opinion within the economics profession on the minimum wage. While minimum wage laws have historically enjoyed a good degree of support among the public, dating back to the first minimum wage legislation following the Great Depression, there had been a longstanding consensus among economists that minimum wages have adverse effects on low-skilled employment. A 1979 American Economic Review study reported that 90 percent of academic economists believed that minimum wage policies generally cause higher unemployment among low-skilled workers. By 2000, however, only 73.5 percent of respondents to an update of the survey agreed wholly or partially with that claim.

The historical consensus that minimum wages cause unemployment stemmed from the conclusions of the textbook competitive labor market model, in which the minimum wage acts as a price floor. The price floor is set above the wage employers would be willing to pay to low-productivity workers like teenagers and the less educated, so the quantity demanded of these workers decreases. This view was famously articulated in Nobel Prize-winning economist George Stigler's seminal 1946 article, The Economics of Minimum Wage Legislation. Responding to the federal minimum wage proposal of 1938, Stigler argued that the legislation could reduce employment by as much as several hundred thousand workers.

Today, however, Stigler's view does not command the near-unanimous assent that it once did. In a 2006 survey of 102 studies on the minimum wage, economists David Neumark of the University of California, Irvine and William Wascher of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors noted that past estimates on employment elasticities — the percent change in employment corresponding to a unit change in the minimum wage — range from significantly negative to slightly positive. Neumark is quick to note, however, that "most of the evidence says there are disemployment effects" and that claiming the evidence is all over the map is misleading.

In their recent book What Does the Minimum Wage Do?, however, Dale Belman of Michigan State University and Paul Wolfson of Dartmouth College argued in a meta-analysis on the subject (that is, a study of studies) that "employment effects [of minimum-wage increases] are too modest to have meaningful consequences for public policy in the dynamically changing U.S. labor market," according to the book's website. Why have study results been so varied? Several explanations, both theoretical and empirical, have been offered. The current state of opinion among economists is unclear, and uncovering the root of the decline of the consensus is difficult. One likely factor, however, is the recent variation in state-level minimums and the opportunity such variation provides for new methods of comparative study.

Monopsony in the Labor Market

The work often considered as the beginning of the modern minimum wage debate is an oft-cited 1994 American Economic Review article, in which David Card of the University of California, Berkeley and Alan Krueger of Princeton University looked at the effects of minimum wage increases on fast-food workers in mid-Atlantic states and controversially found that the minimum wage seemed to increase, rather than decrease, employment. While publishing their paper, Card and Krueger had alleged a publication bias in the economics profession and suggested that some of the historical consensus about the minimum wage could be attributed to a predisposition on the part of scholars and editors toward favoring research that found significant negative effects over work that showed neutral or positive effects.

To explain the unconventionally positive employment effects they detected, Card and Krueger suggested that the labor market may not be as competitive as economists had previously thought and that one explanation might be a degree of "monopsony" in the market, a classic type of market failure. Just as firms may have monopoly power in markets where they are the sole seller of a good, firms may also have monopsony power in the labor market if they are effectively the sole buyer or employer.

In a competitive market, wages are determined by supply and demand, all firms pay the given competitive wage, and the cost at the margin of one extra worker is simply that wage. When firms are the sole buyer of labor, however, they have the ability and the motive both to pay wages that are too low given the productivity of their workforce and to restrict employment. The key is that a monopsonist's labor demand affects the market wage in a way that an individual competitive firm's demand doesn't — that is, they are price-setters, not price-takers.

In other words, if a monopsonist demands just one extra worker, she ends up increasing the market wage for all workers, as her demand is the market demand. In this way, the added cost of an extra worker increases for every worker hired, a phenomenon known as increasing marginal cost. The cost of one extra worker, or her cost at the margin, will not just be the added wage but the wage increase across her entire workforce. She will therefore under-employ as well as underpay.

By setting a minimum wage above what the monopsonist is paying, the government essentially makes the extra cost per worker the same for all workers, meaning the monop-sonist's costs at the margin are constant instead of increasing with each added employee. Facing these constant marginal costs, the employer will increase her workforce in order to profit maximize. It follows, then, that a well-placed minimum wage could induce the monopsonist to both raise wages and hire more.

But how plausible is it that monopsony actually exists in the low-wage labor market? On this question, economists disagree. In a 2010 Princeton working paper, Orley Ashenfelter and Henry Farber of Princeton University and Michael Ransom of Brigham Young University argued that monopsony power is likely pervasive in labor markets. According to their paper, an example of a labor market monopsonist in practice would be a "'company town,' where a single employer dominates." Citing evidence that labor supply is inelastic — in other words, that workers are not highly responsive to changes in their wages — they argued that monopsonistic employers are able to use this inelasticity to their advantage and that the "allocative problems associated with monopsonistic exploitation are far from trivial."

Daniel Aaronson of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Eric French of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and University College London, and James McDonald of the U.S. Department of Agriculture disagree. In a 2007 article in the Journal of Human Resources, they found that the evidence surrounding price changes after minimum wage hikes is inconsistent with the monopsony model. They reasoned that, if the minimum wage increases employment under the monopsony model, it should straightforwardly lead to increased production. This increase in supply should lead to lower prices for the good produced. "Because [monopsonists] will hire on more workers, they'll sell more hamburgers; because they sell more hamburgers, we thought the price should actually fall after a minimum wage hike," says French.

After examining the response of restaurant prices to increases in the minimum wage, however, they found that the opposite was true. Instead of falling, prices rose, a result consistent with the competitive model in which firms pass the extra labor costs on to consumers.

The Hungry Teenager Theory

Another explanation mentioned frequently in the media is the theory that increased wages for some workers stimulate demand for goods produced by low-income workers and offset or even reverse negative employment effects. In the academic literature, this theory has been referred to as the "hungry teenager" effect. The theory first appeared in a 1995 Journal of Economic Literature article by economist John Kennan of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who argued that if a typical minimum-wage worker, such as a teenager, spent his extra wages on minimum-wage-produced goods, then the extra demand could offset any disemployment effects. That increased demand for minimum wage goods would raise their prices. French explains that according to this model, "Firms receive an increase in demand at the exact same time that they have to pay higher wages, which could seriously blunt the effect of higher wages in terms of how many workers a firm might have to shed."

One issue with the theory is that the income effect, the extra consumption spurred by an individual's rise in income, may be dominated by a substitution or price effect, in which a consumer substitutes a good in favor of others when the relative price of that good rises. Many low-income workers (in this example, teenagers) will have higher incomes as a result of the minimum wage, but goods produced by those workers (in this example, hamburgers) are also now more expensive, causing all consumers to buy fewer of them. "Minimum wage advocates always say those price effects won't have any effect on demand," Neumark observes, "but that raises the question of why companies wouldn't raise the price before the minimum wage goes up?"

Another issue, according to French, is that although "household spending actually does go up a lot amongst households with minimum wage workers after a minimum wage hike," goods like hamburgers that are produced by minimum wage workers just aren't that big a share of their budgets. "For that reason, an explanation that claims the minimum wage truly causes that big of an income effect," says French, "just doesn't really work."

In order for the theory to work, the benefit to low-in-come workers would need to be enormous, and low-income workers would need to spend all or almost all of those earnings exclusively on goods produced by other low-income workers. "It's certainly possible to write down a theoretical model in which the additional wages paid to low-wage workers increases consumption by so much that employment doesn't fall," says economist Jonathan Meer of Texas A&M. But "it seems extraordinarily unlikely — the assumptions necessary are practically laughable."

Substituting Low-Skilled Workers for High-Skilled

Another major theoretical explanation for the modest disemployment effects is known as labor-labor substitution. This theory speculates that firms respond to minimum wage hikes by adjusting the make-up of higher- and lower-skilled workers in their workforces. While readjusting a production process may be difficult in the short run, firms may be able to swap out low-skilled workers for higher-skilled workers more quickly as the former become comparatively more expensive.

If this were the case, we would expect to see decreased demand for lower-skilled workers and increased demand for higher-skilled workers in response to a minimum wage increase, meaning the effect on the overall level of employment would be muted — but the changes would hurt the low-skilled. Citing evidence from a 1995 NBER working paper he co-authored with William Wascher of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Neumark explains that it can be hard to tease out the effects on the low-skilled workers from the net effects on general employment; despite modest changes to net employment levels, "what happens to those you're most trying to help can still be pretty severe."

Data Problems?

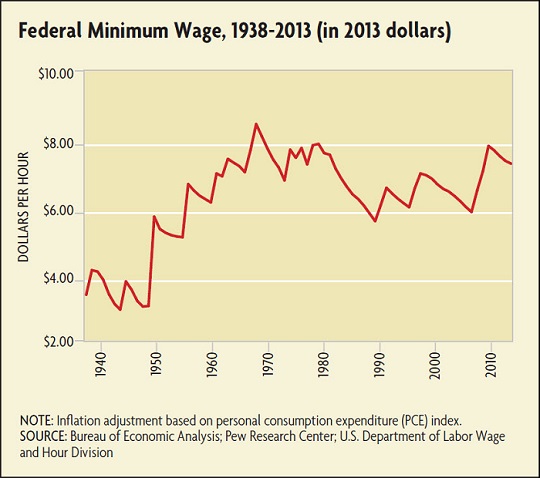

In addition to competing theories about the nature of the labor market, questions have arisen about the means of measuring and interpreting the data surrounding minimum wage and its effects. Several major empirical challenges may affect the ability of economists on both sides of the issue to get an accurate picture of the policy's consequences. One potential issue concerns inflation. Currently, almost four-fifths of all states and the federal government do not index their minimum wages to changing price levels, meaning that the real values of the minimums are eroded over time (see chart), until another one-time nominal increase changes their value. Meer says that even though the United States has not had significant inflation in recent years, the real effects of nominal minimum wage increases are washed away over time. "Over the course of the data we examine, we show that minimum wage increases are eroded fairly quickly relative to comparison states," he says.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.