The Dropout Dilemma

Why do kids drop out of high school, and what can be done to help them finish?

Orangeburg Consolidated School District 5 serves about 7,000 students in rural South Carolina. More than one-quarter of its high school students fail to graduate within four years. Predominantly African-American, Orangeburg is not a wealthy area; median household income in the county is about $33,000, compared with $53,000 nationally, and the unemployment rate is 10.4 percent, nearly double the national average. Nearly 85 percent of the district’s students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches, and many of their parents did not graduate from high school.

"Poverty is our biggest challenge," says Cynthia Wilson, the district superintendent. "We have students growing up in homes where no one is working, and it becomes a cycle we absolutely need to break by graduating more students."

Every September, teachers and volunteers visit the homes of students who haven’t returned to school to find out why and to help them return; lots of kids in Orangeburg drop out because they don’t have transportation, or they get pregnant, or they need to get a job. The district has started offering night classes for students who have children or have to work, and students also have the option of completing their coursework online — on laptops they’ve borrowed from the school, if necessary. Wilson and her staff are taking other steps to improve the district's academics, but they’ve learned that sometimes helping a kid to graduate takes place outside the traditional confines of school.

Is There a Dropout Crisis?

High school graduation rates in the United States rose rapidly throughout much of the 20th century. During the “high school movement,” about 1910 to 1940, the share of the population with a diploma rose from just 9 percent to 51 percent. But around 1970, the averaged freshman graduation rate (AFGR), which measures the share of students who graduate within four years, began to decline, falling from 79 percent during the 1969-1970 school year to 71 percent by the 1995-1996 school year, where it remained until the early 2000s. This stagnation in graduation rates led to widespread concern about a "dropout crisis."

But the AFGR has improved over the past decade, reaching 81 percent during the 2011-2012 school year, the most recent year for which the Department of Education has published data. Another measure of high school graduation, the adjusted cohort graduation rate (ACGR), was 80 percent. (The Department of Education required states to report the ACGR beginning in 2010 to create more uniformity in state statistics and to better account for transfer students. Historical comparisons for this measure are not available.)

The improvement in the overall graduation rate obscures significant disparities by race and income. The ACGR for white students is 86 percent, compared with just 69 percent for black students and 73 percent for Hispanic students. Minority students also are disproportionately likely to attend a “dropout factory,” which researchers have defined as schools where fewer than 60 percent of freshmen make it to senior year: 23 percent of black students attend such a school, while only 5 percent of white students do. The dropout rate for students from families in the lowest income quintile is four times higher than for those in the highest income quintile.

There is also significant regional variation; states with low graduation rates tend to be in the South and the West. In the Fifth District, Maryland and Virginia have the highest graduation rates, with ACGRs of about 85 percent. Behind them are North Carolina, with an 83 percent graduation rate; West Virginia, with 81 percent; and South Carolina, with 78 percent. Washington, D.C., has the lowest graduation rate in the nation: Just 62 percent of D.C. high school students earn a diploma within four years.

Despite the improvement in the national graduation rate, “crisis” is still the term many people use to describe the dropout situation. “People are severely disadvantaged in our society if they don’t have a high school diploma,” says Russell Rumberger, a professor of education at the University of California, Santa Barbara. "One out of every five kids isn’t graduating. You could argue that any number of kids dropping out of school is still a crisis."

Why Graduating Matters

Several decades ago, the disadvantage wasn’t as severe. "If this were the 1968 economy, we wouldn’t worry nearly so much," says Richard Murnane, an economist and professor of education at Harvard University. "There were a lot of jobs in manufacturing then. They were hard work and you got dirty, but with the right union, they paid a good wage."

But as changes in the economy have increased the demand for workers with more education, differences in outcomes have become stark. The wage gap between workers with and without a high school diploma has increased substantially since 1970; over a lifetime, terminal high school graduates (that is, those who don't go on to earn college degrees) earn as much as $322,000 more than dropouts, according to a 2006 study by Henry Levin and Peter Muennig of Columbia University, Clive Belfield of Queens College (part of the City University of New York), and Cecilia Rouse of Princeton University. Dropouts also are less likely to be employed. The peak unemployment rate for people without a high school diploma following the Great Recession was 15.8 percent, compared with 11 percent for those with only a high school diploma. (Unemployment for college graduates peaked at just 5 percent.) Today, the rate for dropouts is still about 2 percentage points higher.

The differences between graduates and dropouts spill far beyond the labor market. Not surprisingly, high school dropouts are much more likely to live in poverty, and they also have much worse health outcomes. High school dropouts are more likely to suffer from cancer, lung disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, and on average their life expectancy is nine years shorter than high school graduates.

High school dropouts also have a much higher probability of ending up in prison or jail. Nearly 80 percent of all prisoners are high school dropouts or recipients of the General Educational Development (GED) credential. (More than half of inmates with a GED earned it while incarcerated.) About 41 percent of all inmates have no high school credential at all.

The high costs to the individual of dropping out translate into high costs for society as a whole. Research by Lance Lochner of the University of Western Ontario and Enrico Moretti of the University of California, Berkeley found that a 1 percent increase in the high school graduation rate for males could save $1.4 billion in criminal justice costs, or $2,100 per additional male high school graduate. Other research estimates savings as high as $26,600 per additional graduate.

High school dropouts also generate significantly less tax revenue than high school graduates, while at the same time they are more likely to receive taxpayer-funded benefits such as cash welfare, food stamps, and Medicaid. While the costs vary by race and gender, Levin and his co-authors found that across all demographic categories the public health costs of a high school dropout are more than twice the cost of a graduate. In total, the researchers estimated that each additional high school graduate could result in public savings of more than $200,000, although they noted that their calculations do not include the costs of educational interventions to increase the number of graduates.

Raising the high school graduation rate could have economic benefits beyond saving the public money. In many models of economic growth, the human capital of the workforce is a key variable. That's because a better-educated workforce generates new ideas and can make more productive use of new technologies; more education thus equals more growth. Although this connection has been difficult to prove empirically, many researchers have concluded that the rapid growth in educational achievement in the United States during the 20th century, particularly the dramatic increase in high school education in the first half of the century, was a major contributor to the country’s economic advances.

Is Dropping Out Irrational?

Economic models generally assume that people are rational, carefully weighing the costs and benefits of an action before making a decision. So given the large returns to education and the poor outcomes for workers without a high school diploma, why would anyone drop out?

Part of the answer might simply be that teenagers aren’t rational. A growing body of neurological research has found that adolescents have less mature brains than adults, which contributes to more sensation-seeking and risky behavior. But while teenagers might be more impulsive than adults, they don’t generally wake up one morning and suddenly decide to quit school; instead, there are a multitude of factors that over time could lead a student to decide the costs of staying in school outweigh the benefits.

One factor could be that teenagers place less value on the future benefits of an education. Research has found that "time preference," or the value a person places on rewards today versus rewards tomorrow, varies with age. Teenagers are more likely to prefer gratification today.

Students also might not expect the benefits of staying in school to be very large. Many low-achieving students wind up being held back a grade; for these students, staying enrolled in school doesn't actually translate into greater educational attainment. In a study of students in Massachusetts, Murnane found that only 35 percent of students who were held back in ninth grade graduated within six years; the students who dropped out might have perceived that staying in school was unlikely to result in a diploma. The same calculation likely applies to students who live in states where exit exams are required for graduation, as is now the case in about half the country. Students who don’t expect to pass the exam have little incentive to remain in school. Multiple studies suggest that exit exams reduce high school graduation rates, particularly for low-income and minority students.

In April, South Carolina eliminated its exit exam requirement for future students and is allowing students who failed the exam in the past to apply retroactively for a diploma. That's a benefit for those students, but it poses challenges for educators. "If someone without a high school diploma has the opportunity to make $10,000 more by getting a diploma, you want them to have that opportunity," Wilson says. "But we have to find our ways to keep our students motivated to do more than just get by. We can’t say anymore, 'You really have to learn this because you have to pass that test!'" In addition, exit exams were introduced to ensure that high school graduates had achieved a certain threshold of knowledge. Eliminating them poses the risk that graduates won’t be adequately prepared for the workforce or for postsecondary education.

The increasing focus on college attendance at many high schools might also encourage kids to drop out. Students who aren't academically prepared for college or who don’t want to attend may see little value in finishing high school if they perceive a diploma solely as a stepping stone to college. The focus on college prep might also contribute to the fact that many dropouts report feeling bored and disengaged from school.

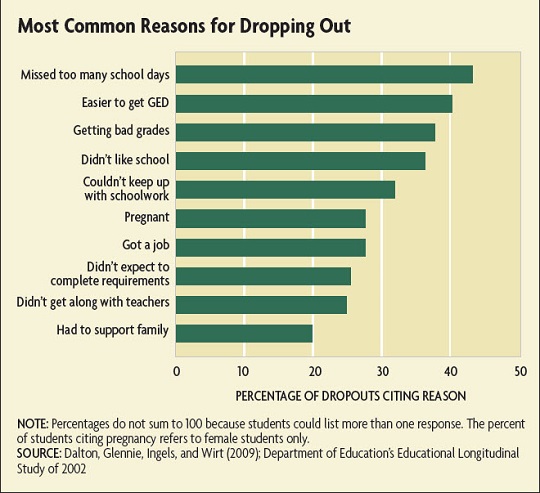

For some students, the opportunity cost of attending school — the value of the other ways they could use their time — may be quite high. In a survey of high school students conducted by the Department of Education, 28 percent of female students said they dropped out because they were pregnant, 28 percent of all students quit school because they got a job, and 20 percent needed to support their family. (See chart.)

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.