Post-Recession Labor Market Trends in the Fifth District

Dislocations in the labor market during the Great Recession were severe and the recovery was slow. It took slightly more than four years for the number of jobs to return to pre-recession levels in the Fifth District, and the unemployment rate remained higher more than six years after the recession ended. The effect varied across regions and industry sectors, however. The least-affected industry sectors enjoyed rapid turnarounds once the recession ended; for example, the education and health sector never experienced job loss and has grown at a healthy pace since the end of the recession. In contrast, other sectors, those most heavily hit by the recession, experienced very shallow recoveries with slow job growth and have yet to fully recover jobs lost during the recession.

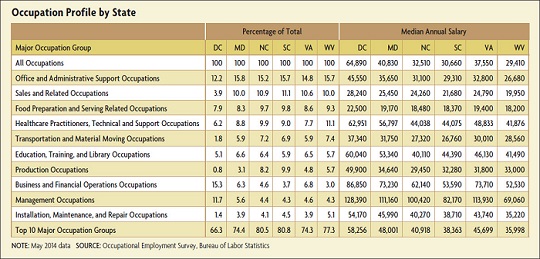

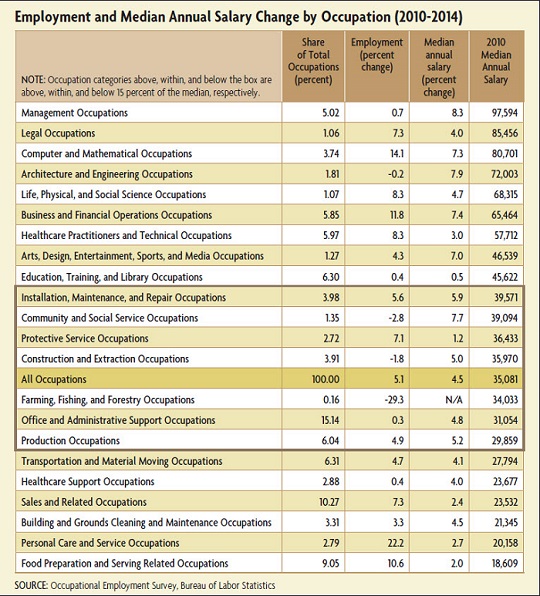

Underlying these trends are changes in the skill sets and experience sought by firms. Economists have noted that as technology has become more widely diffused through the economy, businesses have been seeking workers with different skill sets than in the past. Technology has created new jobs while making others obsolete or less abundant. In particular, economists have found that employment growth has been stronger for higher-skilled jobs and for lower-skilled jobs while there has been less demand for middle-skilled jobs. Looking at occupation data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), it appears that this trend has been at work in recent years in the Fifth District as higher-skilled and lower-skilled occupations have experienced greater employment growth than middle-skilled occupations.

Industry Sector Trends

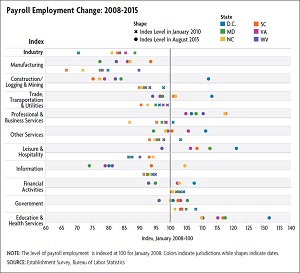

The Great Recession had varying effects on different sectors of the Fifth District economy. The two sectors most negatively impacted during the downturn were the construction and manufacturing sectors. The collapse of the housing market resulted in a sharp decrease in employment in the construction sector as well as a number of other sectors that feed into the housing sector: retail and wholesale trade, transportation, finance, and manufacturing. The manufacturing sector was heavily affected by the broad decline in domestic and foreign demand for U.S.-produced goods, both consumer and industrial. The total declines in Fifth District employment in construction and manufacturing were 24 percent and 16 percent, respectively, from January 2008 to January 2010, far greater than the 5.6 percent decline in employment across all sectors. (Although the recession technically began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009, this article uses January 2008 and January 2010 to allow for full-year comparisons and minimize seasonality issues.)

Notably, not only were these two sectors most greatly affected by the recession, they were the slowest to recover (excluding the information sector, mainly print and telecommunications, where the continued decline in employment represents a secular decline due to structural changes rather than cyclical factors). From January 2010 to August 2015, employment growth in the housing and manufacturing sectors increased 5.5 percent and 4.3 percent, respectively, well below the Fifth District industry average of 8.1 percent.

While job loss in the manufacturing and construction sectors was severe across the Fifth District during the recession, there was considerable variation among states. But in the Fifth District states with the largest manufacturing sectors, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and West Virginia, the losses were fairly comparable — between 14 percent and 19 percent. Job growth since January 2010 has varied, as well. There has been little increase in jobs in Virginia and West Virginia, despite strong production in auto manufacturing and chemical manufacturing in West Virginia. In contrast, the auto and aerospace sectors have driven growth in the manufacturing sector in North Carolina and South Carolina in recent years. Manufacturing employment in both states has improved considerably — up 7 percent and 13 percent, respectively, but still remains well below pre-recession levels.

The decline in the construction sector during the recession varied across jurisdictions. South Carolina experienced the largest decline, followed by North Carolina — 33 percent and 27 percent, respectively. Interestingly, the metro areas of the Fifth District that were most caught up in the housing boom and subsequent collapse were in the northern part of the district, Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. Yet the decline in construction employment in Maryland and the District of Columbia was not as severe as in the Carolinas.

In any event, the recovery in construction employment has been lackluster. With the exception of West Virginia, there have been increases in construction jobs, but the level of employment in August 2015 was well below pre-recession levels. The recovery in the single-family housing market has been very moderate; while construction of multi-family housing units has been strong, particularly in the Washington, D.C., region, it has not been enough to offset the softness in the single-family market.

Where there have been significant gains in employment in recent years has been in services. The professional and business services sector, the leisure and hospitality sector, and the education and health sector have each seen significant growth since 2010 with increases of 16 percent, 15 percent, and 11 percent, respectively. Notably, these sectors all experienced more moderate employment declines (or no decline at all in the case of education and health) relative to other sectors during the downturn. Professional and business services and leisure and hospitality declined 4.8 percent and 4.3 percent, respectively, while employment in education and health grew by 3.6 percent from January 2008 to January 2010. The employment increases in the professional and business services and leisure and hospital sectors have been widespread across jurisdictions, with the exception of leisure and hospitality in West Virginia, where there has been little to no net growth since January 2010.

Different factors influenced the goods-producing and service-providing sectors across Fifth District jurisdictions. As mentioned earlier, the growth of the auto and aerospace sectors in the southern part of the district resulted in employment gains and additional investment in those sectors, as did ancillary sectors that served as suppliers and distributors. The shale gas boom affected the demand for manufactured goods, construction, and the provision of services in West Virginia. Federal spending cuts heavily impacted service-providing sectors in the northern jurisdictions.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.