Education and Vulnerability to Economic Shocks in the Carolinas

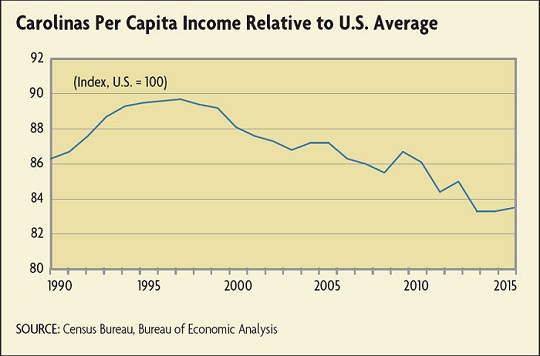

The role of technological disruption in the economy and its effect (actual and potential) on workers is a lively topic of discussion among labor market economists. Certainly, the steady — some would say accelerating — march of information technology and robotics into the workplace, coupled with lingering anxieties from the Great Recession, has heightened workers' insecurities about their own place in the economy of the future. Technological changes, combined with other economic forces, dramatically altered the economic landscape of the Carolinas over the course of a generation. During this evolution, the region’s economy evolved to look less like it did in the 1990s (overly reliant on manufacturing) and more like the national economy of today.

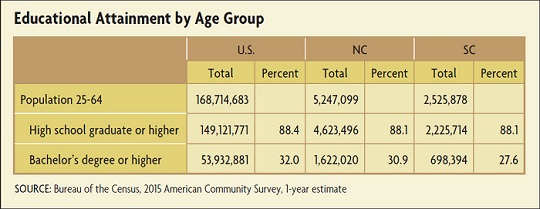

Still, the region and its workers appear more exposed to economic disruptions than with the nation as a whole. In some measure, this vulnerability can be viewed as a human capital development challenge. The states need to do a better job of training workers for today's economy as well as preparing them for the disruptions that will inevitably come in the future, whether those disruptions are technological or cyclical in their origin.

Technological Disruptions and Changing Industry Structure

In the Carolinas, the region's experience with economic disruptions (cyclical and technological) in its manufacturing industries is relatively recent when compared to similar travails in the New England and Midwestern regions of the United States. Indeed, for many years, the Southeastern United States generally, and the Carolinas specifically, successfully lured some of those other regions' mainstay manufacturing industries, such as textiles and vehicle production. The reasons for manufacturing's migration south are many — the spreading use of air conditioning, lower labor costs, and relatedly, low unionization rates, to name just a few.

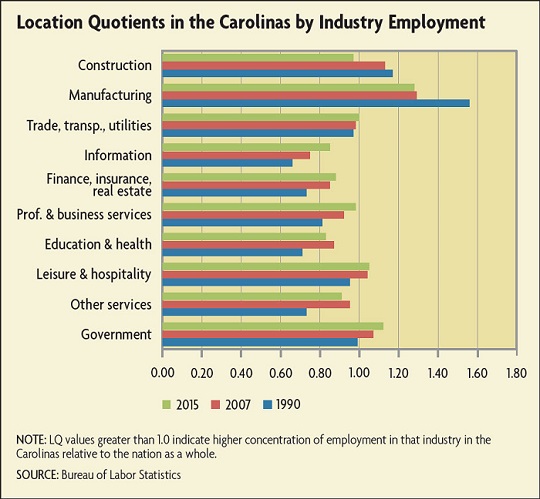

Thus, North Carolina and South Carolina both developed hard-earned reputations as "manufacturing states." As recently as 1990, manufacturing firms employed nearly 1.2 million workers in the two states. Moreover, the Carolinas' employment base had become more manufacturing-intensive than some traditional industrial giants such as Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin. In 1990, manufacturing accounted for a little more than 30 percent of private payroll employment in the two states combined, whereas it accounted for between 25 percent and 27 percent of jobs in Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

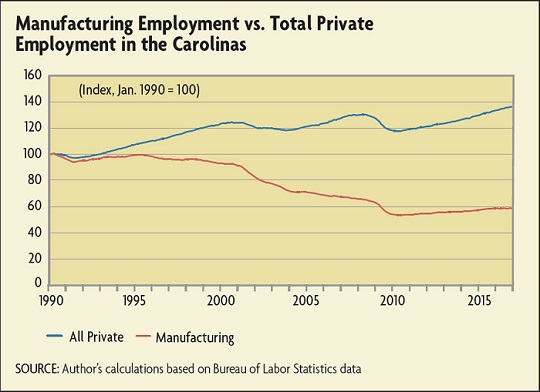

But in the lead-up to the new century, employment in some of the region's important manufacturing industries came under pressure from (among other factors) changing consumer demands and technological advances. These technological advances were not limited to improvements in capital equipment, such as robotics and automation. They also included efficiencies gained from so-called process technologies — such as improved logistics, outsourcing (and "off-shoring"), and global sourcing business models. The result was that the two states saw manufacturing jobs eroding during the 1990s and falling throughout the first decade of the new millennium leading into the Great Recession. In fact, manufacturing employment in the two-state region fell by more than 406,000 between 1990 and 2007, or by more than 34 percent. And manufacturing's share of total private employment fell to 16 percent (from 31 percent) and actually ended up below the comparable share in each of the Midwestern states noted above (Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin).

During this period of industrial restructuring, many argued that the loss of manufacturing jobs would doom the states' economies. It didn't. While manufacturing jobs were on the decline, innovative businesses and people in the two states were creating jobs in other industries, many of which would have been hard to predict 10 years earlier. Firms brought new and innovative goods and services to consumer and business markets. And they created jobs, lots of them. Between 1990 and 2007, total private employment in the two states plowed forward even as technology was depressing manufacturing employment. (See chart below.)

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.