A Capital Compromise

How war debts, states' rights, and a dinner table bargain created Washington, D.C.

By the summer of 1783, soldiers in the Continental Army were fed up. The British army had surrendered at Yorktown, Va., two years earlier, effectively ending the Revolutionary War, but soldiers remained on duty while treaty negotiations dragged on in Paris. They hadn't been paid in full for their service in years, and when the Continental Congress passed legislation furloughing them, they suspected they never would be. On June 21, around 400 angry members of the Pennsylvania militia surrounded the building in Philadelphia where the Congress met, scaring off so many delegates that legislators failed to achieve a quorum. Alexander Hamilton and other congressional leaders urged Pennsylvania's government to send in friendlier troops for protection, but the state refused. The next day, the Congress announced it was abandoning Philadelphia in favor of Princeton, N.J.

Over the next few years, legislators would meet in Annapolis, Md., Trenton, N.J., and New York City. In 1788, the Constitution gave Congress the power to establish a permanent home for the federal government, but there was considerable disagreement among the states' delegates about where that home should be. Eventually, the debate would become entangled with arguments about the nation's finances, reflecting deep philosophical divides between the country's founders. The compromise that was eventually reached in 1790, which created a new district on the banks of the Potomac River, had long-lasting political and economic repercussions for the region and for the country.

"Not Worth a Continental"

When the Revolutionary War began in 1775, the American rebels weren't lacking in courage, but they were lacking in currency. The Second Continental Congress didn't have any authority to raise revenue to fund the army. "Not then organised as a nation, or known as a people upon the earth — we had no preparation — Money, the nerve of War, was wanting," George Washington wrote in an early (and eventually discarded) draft of his first inaugural address.

The Congress formalized its own existence with the Articles of Confederation in 1777, but its power was limited to requesting supplies and money from the states — requests the states failed to fulfill. "The individual States, knowing there existed no power of coertion [sic], treated with neglect, whenever it suited their convenience or caprice, the most salutary measures of the most indispensable requisitions of Congress," according to Washington.

So the Congress financed the war by printing money: up to $240 million in face value, the equivalent of nearly $6 billion today. The fledgling government also took loans from France, Spain, and private Dutch investors and issued scores of "loan office certificates," which were basically IOUs to merchants and citizens who provided goods to the army. The individual states also printed their own currency — Pennsylvania had 250 different forms of notes — and issued various bills of credit and bonds. These were specified in a confusing array of currencies and commodities. One Massachusetts debt issue promised to repay bondholders "according as five bushels of corn, sixty-eight pounds and four-seventh parts of a pound of beef, ten pounds of sheeps wool, and sixteen pounds of sole leather shall then cost."

Within a few years, Continental notes were worth pennies on the dollar. Store owners used them as wallpaper and the phrase "not worth a Continental" entered the American idiom. Eventually, the Congress couldn't pay its soldiers or the interest on the national debt. When the war ended, the Congress didn't even have enough specie to buy paper on which it could print certificates promising to pay soldiers in the future.

The Federalist Plan

In the late 1780s, the new country's finances were in disarray. Without a functioning currency, the government of Virginia started accepting deer skins — "well dressed for the purposes of making breeches" — as payment for debts. A former general in the Revolution wrote that "money is now no more a currency than the ragged remains of a kite."

One of the framers' goals in drafting the Constitution, which was ratified by a majority of the states in 1788, was to address many financial woes by creating a stronger federal government with the authority to tax and regulate commerce. But the matter of the Revolutionary War debt remained; in 1790, the outstanding state and federal debt totaled at least $70 million, or nearly $2 billion in today's dollars. One proposal to deal with the debt was to pay out the face value to the original debtholders who had held onto their notes but pay only the depreciated market value to those who bought on the resale market. Initially, the debt was owned largely by soldiers, store owners, and farmers. But in later years, it was bought up by speculators, primarily from the North, for far less than the original value. According to research by historian Cathy Matson of the University of Delaware, just 47 Northerners, primarily from New York and New Jersey, owned 40 percent of South Carolina's, North Carolina's, and Virginia's combined debts. These new debtholders stood to gain a substantial windfall if the debts were repaid in full.

The new treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, later of Broadway fame, disagreed with this proposal. In January 1790, he submitted the "First Report on Public Credit" to Congress, in which he described the nation's debt as "the price of liberty." The arguments for repaying it in full, without discriminating among debtholders, "rest[ed] on the immutable principles of moral obligation."

Hamilton made a more practical argument for repayment as well. In countries where the national debt was properly funded and "an object of established confidence,"transfers of public debt could function as money and create a larger stock of capital to fund trade, agriculture, and commerce. Repaying the debt and establishing sound public credit would also, in Hamilton's view, solidify the union of the states and increase America's standing with the rest of the world.

To establish this credit, Hamilton, a staunch Federalist, recommended that the federal government assume and consolidate all the outstanding debt and then pass an excise tax to generate the revenues to pay it off. To many people, including fellow Founding Father James Madison, Hamilton's plan seemed like a ploy to increase the central government's power. "Madison was a leading Federalist in creating the Constitution. But he never envisioned a system as centralized as the one Hamilton began trying to create," says Denver Brunsman, a historian at George Washington University. "Hamilton seemed to be proposing a system that matched the one America had just fought against."

Madison and other supporters of stronger states' rights also objected to Hamilton's plan because some states, including Maryland and Madison's home state of Virginia, had already paid off substantial portions of their war debts. Subjecting them to a federal tax would mean they were subsidizing other states' debts. Finally, they hated the idea of Northern speculators profiting at the expense of Southern farmers and merchants. The House rejected Hamilton's plan in April of 1790.

The Compromise

At the same time Congress was debating debt assumption, it was also trying to decide where to establish the nation's capital. Article I of the Constitution gave Congress the authority to establish a district as the seat of the U.S. government. This district would not be part of a state; instead, Congress would have the power to "exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever." The lack of statehood was an "indispensable necessity," according to the framers, in order to prevent state officials from being able to interrupt or influence the federal government's proceedings.

At least 16 different locations had been proposed, the majority of them in the North. Many Southerners feared that a Northern capital would diminish the South's influence, and Madison and other Southern representatives advocated locating the capital in Virginia, on the banks of the Potomac River. But by the spring of 1790, it appeared likely that a geographically central location such as Philadelphia would win the day.

Writing in 1792, Thomas Jefferson, then the secretary of state, recalled running into Hamilton in New York in June of 1790, just a few months after the House rejected his plan. To Jefferson, Hamilton appeared "somber, haggard, and dejected beyond description," so Jefferson invited him and Madison to his home the next day for a "friendly discussion" of their differences. Over dinner on June 20, Madison agreed to stop opposing the debt assumption plan, and even to round up votes in favor of it, if Hamilton would help him deliver the capital to Virginia. "It was observed … that as the pill [of debt assumption] would be a bitter one to the Southern states, something should be done to soothe them," Jefferson wrote. "The removal of the seat of government to the Potomac was a just measure, and would probably be a popular one with them." On July 16, Congress passed the Residence Act, which created "a district of territory, not exceeding ten miles square, to be located as hereafter directed on the river Potomac." A few weeks after that, Congress approved Hamilton's Funding Act.

Jefferson would come to oppose debt assumption — and Hamilton himself. When the compromise was reached, he had recently returned from several years in France and was unfamiliar with the domestic debates. "Jefferson wanted to play the role of diplomat and mediator and thought that helping resolve Hamilton's and Madison's dispute would bring the country together," says Brunsman. "But he would come to believe that he had been duped by Hamilton and that the compromise was his greatest political mistake." Jefferson concluded his recollection of the dinner with the following observation: "[Debt assumption] was unjust, in itself oppressive to the states, and was acquiesced in merely from a fear of disunion, while our government was still in its most infant state. It enabled Hamilton so to strengthen himself by corrupt services to many that he could afterwards carry his bank scheme and every measure he proposed in defiance of all opposition."

Cutting the Diamond

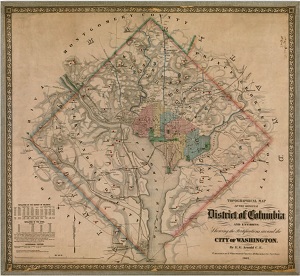

The selection of the new capital's precise location was left to President Washington, who selected a site centered on the Maryland shore of the Potomac, extending in a diamond shape nearly to Mount Vernon. (See map.) The first boundary stone was laid in 1791, and Congress convened in the District of Columbia for the first time in November 1800. (Philadelphia served as the temporary capital while D.C. was being built.) Washington remained intimately involved in the district's planning and construction, but he never had the opportunity to govern from the new capital; he left office in 1797 and died two years later. The first president to take the oath of office in Washington, D.C., was Jefferson.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.