Another part of the story lies in both long-standing and more recent economic developments. In the past few decades, as local mining, manufacturing, and agricultural employers have left rural areas, the loss of employer health coverage has contributed to the financial challenges of rural hospitals. Some demographic trends, such as an increasingly older population in rural areas, have made inpatient services more in demand, but others, such as a declining population overall, have made it more challenging for rural hospitals to operate profitably. The GAO found that rural hospitals have also faced increased competition from federally qualified rural health centers and urban hospitals. These competitors provide services that rural residents had previously sought at their local hospital, such as emergency care and behavioral health care. Sometimes, rural patients will bypass their local rural hospital for larger rural or urban facilities even when services are available locally. One study found no effect of hospital closures for Medicare patients and found that hospital closings were associated with reduced readmission rates, which is regarded as a sign of increased quality.

Health care policy matters, too. The last string of rural hospital closures occurred in the 1980s after Congress mandated the use of fixed, predetermined reimbursement rates for hospitals through the prospective payment system (PPS). In response, then, to growing concerns over rural health care access, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services implemented the Rural Hospital Flexibility Program of 1997 (commonly called the "Flex Program"), which authorized payment of inpatient and outpatient services on a "reasonable cost basis" for hospitals designated as CAHs. According to an issue brief from the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2016, more than half of rural hospitals were CAHs, about 13 percent were designated as Sole Community Hospitals (SCHs), 8 percent were Medicare-Dependent Hospitals (MDHs), and another 11 percent were Rural Referral Centers. All of these designations provide enhanced or supplemental reimbursement under Medicare.

Federal law requires that hospitals treat patients regardless of their ability to pay, which means all hospitals have some amount of uncompensated care. In 2017, hospitals nationwide provided approximately $38.4 billion in uncompensated care. Hospitals with high levels of uncompensated care, formally known as Disproportionate-Share Hospitals (DSHs), receive federal financial assistance, although it only covers approximately 65 percent of total uncompensated costs. The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was intended to reduce the federal government's financial assistance to DSHs on the assumption that more uninsured patients would have their services covered by Medicaid soon after the passage of the ACA. But as of mid-2019, 14 states have not expanded Medicaid (including North and South Carolina in the Fifth District). States that expanded Medicaid to low-income adults under the ACA saw both larger coverage gains and larger drops in uncompensated care — a 47 percent drop in uncompensated care costs on average compared to an 11 percent decrease in states that did not expand Medicaid. A 2018 article in the journal Health Affairs found, in fact, that the ACA's Medicaid expansion was associated with better hospital financial performance and notably lower likelihoods of closing, especially in rural markets and counties that had large numbers of uninsured adults before Medicaid expansion. Almost 75 percent of the rural hospitals that closed from 2010 through mid-2019 were in states that did not expand Medicaid.

A Negative Spiral

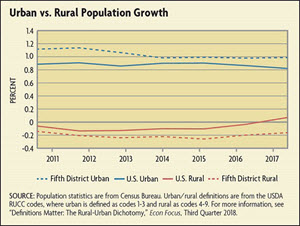

The CAHs that closed from 2010 through 2014 generally had lower levels of profitability, liquidity, equity, patient volume, and staffing. Other rural hospitals that closed had smaller market shares and operated in markets with smaller populations. No doubt delayed and forgone Medicaid expansion — and higher rates of Medicare coverage due to an aging population — exacerbated the financial strain facing rural hospitals that were already struggling with declining population, higher poverty, and relatively more uninsured.

Marc Malloy, a senior vice president with the hospital and medical facilities chain HCA Healthcare, notes that these economic disadvantages of rural hospitals can lead to a negative spiral. "Smaller hospitals are significantly disadvantaged when competing for resources, negotiating with commercial payers, and attracting top talent — both clinical and managerial," he says. "As finances get tighter, it becomes difficult to attract doctors in high-margin businesses like orthopedics, vascular surgery, pediatrics, or maternal care. The tough finances leave the board of directors with the dire choices to sell a failing hospital or reduce services until the organization has atrophied to the point of closure."

The challenges of staffing rural hospitals are found across states. Glenn Wilson, chairman and CEO of Chesapeake Bank and Trust in Maryland, who is also on the University of Maryland Medical System Shore Regional Health Board, says it is challenging to attract physicians who might see half the number of patients in a rural area than they would in an urban area and to retain nurses whose hours will vary unexpectedly from day to day based on the number of patients on any given day."State health care regulators are not adequately recognizing that in a more rural setting, the costs of providing health care will be higher. We can't scale down but so far."

What Happens to Access to Health Care?

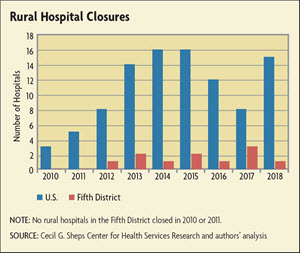

The most common immediate effect of any rural hospital closure is lost access to health care. According to the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina, the 106 rural hospitals that closed from January 2010 through January 2019 represented a loss of 3,984 hospital beds in rural areas. For the closures that occurred from 2013-2017, over half were at least 20 miles from the nearest hospital, indicating that hospital closures might even hurt access to emergency services. Although hospitals' inpatient volumes continue to decline, the use of emergency services, especially at the CAHs, has not declined, corroborating that rural communities need local emergency access.

There are other services that go away when the local hospital closes. Closure of obstetrics units or reduction of maternity services in rural areas prolongs travel time for rural women, which is associated with higher costs, greater risk of complications, longer lengths of stays, and psychological stress for patients. Research has indicated that the loss of hospital-based obstetric care in rural counties not adjacent to urban areas was significantly associated with increases in births in hospitals lacking obstetrics units and increases in preterm births. Access to mental health care and treatment for substance abuse disorders is also more likely to be in short supply once rural hospitals are closed.

Cutbacks in services in rural facilities may be driven in part by potential quality issues arising from low volume. "Research indicates that volume and quality outcomes are positively correlated," says Malloy. Speaking of his experience at Mission Health in Asheville, N.C., sold to HCA in February 2019, he recalls, "At Mission, we closed labor and delivery services at two of our outlying hospitals because the volumes were so low. We felt that to ensure the highest quality and best outcomes, it was better to move those services to a facility that had the volume to ensure sufficient staffing, skills, and experience."

What About Jobs?

In many rural communities, a hospital can be a primary source of jobs — often skilled, higher-paying jobs. When a hospital goes away, then, so do those jobs (although in many cases, hospitals do convert to other facilities, providing more limited, or just different, services). According to a 2017 article by Anne Mandich and Jeffrey Dorfman of the University of Georgia, a short-term general hospital is associated, on average, with 559 jobs in its county, 60 of which are hospital based and 499 of which are not health care related. In addition, hospital employees with an associate's degree have a 21.4 percent wage premium when compared to other opportunities, and those with a bachelor's degree can earn 12.2 percent more. A 2006 article in the journal Health Services Research reported that the closure of a community's only hospital reduces per capita income by 4 percent and increases the unemployment rate by 1.6 percentage points. They also found that there was no long-term economic impact from closures in communities with alternative sources of hospital care, although overall income in the area decreased for two years after the closure.

An article published in 2015 tried to estimate the economic impact of a hospital closure on a rural area and used as a case study Bamberg County Memorial Hospital in South Carolina, which closed in 2012. When it closed, the hospital employed 102 people and created over $3 million in direct labor income. (Ten of the displaced workers were rehired when the medical center in adjoining Orangeburg County opened a new urgent care center.) The case study found that, not surprisingly, in the two years after the closure, Bamberg County had a larger decrease in population and employment than contiguous counties.

The Anchor Institution

The case study on Bamberg County documented not only changes in access to care and transport times to health care, but also social effects of the closure. According to the article, Bamberg County Memorial, as an anchor institution in the area, had been a social hub for the community and gave many young people their first work experience (and many older residents, their last).

In addition to lost employment for an area, a hospital closing leads to the exodus of medical professionals, such as doctors and nurses. Not only does this reduce overall employment and shrink the pool of higher wage earners, thus reducing the purchasing power of a community, but the departure of the medical professionals also means the loss of individuals who may act as role models, mentors, volunteers, and patrons within the community. This loss, while difficult to quantify, should not be discounted.

Moreover, communities that wish to attract businesses must have a compelling portfolio of value that includes high-quality health care. This could apply to retirement communities that might locate within a certain number of miles of a hospital or even to colleges if parents are concerned about proximity to health care in the event of an emergency. Some employers have mentioned taking a region's health care facilities into account when considering where to locate a plant or an office, and all employers mention the presence of a qualified, healthy workforce as key to site location decisions.

What's Next?

The high rate of rural hospital closures is not expected to slow anytime soon — instead, some analysis suggests that they may close at an even higher rate in coming years. Some 430 hospitals across 43 states are at a high financial risk of closing based on an assessment of their current financial viability. Together, these hospitals are major economic contributors to their communities, representing 21,547 staffed beds, 150,000 jobs, and $21.2 billion total patient revenue. And almost two-thirds of these hospitals are essential to the surrounding community, meaning they provide critical trauma care, serve vulnerable populations, are located in geographically isolated areas, or have a substantial economic impact on the local community.

Within the Fifth District, 21 rural hospitals in North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia face a high financial risk of closing. This represents nearly one in five rural hospitals in those states. Of additional concern is the fact that 14 of the rural hospitals at high risk of closing in North Carolina, South Carolina, and West Virginia are considered essential to their communities. West Virginia has the highest number of essential rural hospitals at high financial risk of closing, as eight of the state's 10 at-risk hospitals are considered essential to their communities.

Every now and again, a hospital will reopen, such as Crockett Medical Center in Texas. Through a tax increase and reduced services (for example, it is operating a primary care clinic and an emergency room but not an obstetrics unit), the hospital managed to resume some operations and provide its resident access to at least some care. There might be other models that could provide rural residents with emergency care. For example, some communities might be able to cease providing inpatient services but still generate enough outpatient revenue to maintain an emergency department. One report found that although half of hospitals that closed from 2010 through 2014 ceased providing health services altogether, the rest have since converted to an alternative health care delivery model. Some options include independent clinics, hospital-owned primary care practices, provider-based and independent rural health clinics, urgent care clinics, off-campus emergency departments, clinic and ambulance services, rural emergency hospitals, and 12-hour primary health centers.

The way forward will inevitably vary by state. Maryland, for example, is the only state in the country that is exempt from the Medicare hospital reimbursement rules and thus any federal pressure to focus on rural health will not affect Maryland. Virginia has seen far fewer rural hospital closures in part because the state has many multi-hospital health systems; according to Sean Connaughton, president and CEO of the Virginia Hospital and Healthcare Association, "It is the small, stand-alone hospitals that are the hardest to keep open." Given the negative operating margins of most small rural hospitals, it seems likely that the mergers, acquisitions, or closures of rural hospitals are likely to continue. But Connaughton also sees partnership opportunities across rural health care that could enable a hub-and-spoke network of providers that sustainably provide training and health care. One example from Virginia is in the Roanoke Valley region, where Carilion Clinic is working with partners like Virginia Tech on medical education and Radford University on nursing education while engaging its network of rural hospitals to refer patients needing specialty care to larger hospitals such as Roanoke Memorial Hospital.

Conclusion

Sometimes, an acquisition can provide a health care system with its best hope of survival. Says Malloy of the sale of Mission Health to HCA in 2019, "The arrangement with HCA paints a far brighter future than we would have had otherwise." This is less likely to be true of a hospital closing, however, even if a closure is unavoidable and even if there are viable alternatives to health care within a short distance. Closing any anchor institution has the potential to affect a community heavily in terms of care, jobs, and the presence of potential role models and pillars of the community. It is important, then, for policymakers and leaders at all levels of government to help consider the best ways to help that community move forward.